Cromwell Day

Cromwell Day provides dedicated time and space for reflection and education about diversity, racism, and inclusion. Originally established to celebrate the legacy of Otelia Cromwell, class of 1900, Smith’s first African American graduate, Cromwell Day has been a Smith tradition since 1989. The day has since expanded to also celebrate Cromwell’s niece, Adelaide Cromwell ’40, who was the first African American professor appointed at Smith. Through the work of the Office for Equity & Inclusion (OEI), together with campus partners, the college seeks to take individual and community responsibility for our behavior with an awareness of how that behavior furthers and disrupts patterns of structural oppression.

Cromwell Day Offers Smith College Community Hope in Contentious Times

From a keynote address by diplomat and scholar Farah Pandith ’90—who, as a student, helped found the annual event—to workshops, special exhibits, and performances, the day offered numerous opportunities for reflection about diversity, racism, and inclusion.

Reflecting to Look Forward

Cromwell Day 2025 celebrated community, resilience, and mindfulness. Take a look at some highlights from the day’s activities and workshops.

The History of Cromwell Day

By Floyd Cheung, Vice President for Equity & Inclusion; Professor of English Language & Literature and American Studies

Download the History of Cromwell Day PDF

Smith College has confronted racism since it opened its doors in 1875. As at many other colleges and universities, racial hostility intensified in the late 1980s and early 1990s, becoming more frequent, more visible, and more damaging.1

The history documented here provides context for how Smith has, over time, responded to incidents of racism, including creating what is now known as Cromwell Day.2 This account is offered as a contribution to shared understanding and ongoing dialogue about ways that Smith can continue to live and lean into its values of equity and inclusion.

Concrete steps to address the campus climate were particularly urgent in the early 1990s, following a series of disturbing incidents. In a 1993 report to President Mary Maples Dunn titled “A Record of Racist Notes at Smith College,” Assistant Dean for Minority Affairs Marjorie Richardson enumerated some of these acts. In November 1986, an inscription was discovered on the steps of Lilly Hall—then home to the Mwangi Multicultural Center—that addressed students of African, Asian, and Latine descent with the most heinous epithets imaginable, telling them to “quit complaining or get out.” Also at the time, students of all racial identities were calling for the college to divest from the South African government to protest against its system of apartheid and for the college to require racial literacy education. The report added that from 1987 to 1989 at least nine “threatening and racist notes” targeted individual domestic and international students of African and Asian descent.3 In January 1989, two white students received homophobic notes.4 That fall, antisemitic graffiti appeared in the Smith College bookstore.5

The community demanded action.

On Jan. 15, 1989, President Dunn and the board of trustees established a Civil Rights Policy and created a position to oversee it. The goal was to sustain “a community that respects and promotes diversity and individualism.”6 From 1988 until 1991, Dean of the Faculty Robert Merritt sponsored the Fund for a More Inclusive Curriculum to “encourage the study of world cultures and American cultures beyond the traditional focus on Western Europe and white America.”7

Students and faculty also called for collective listening and learning. The Society Organized Against Racism (SOAR)—composed of students, staff, and faculty and led by Professor Tom Riddell—suggested “annual programs of community education.”8 Concerned Students of All Colors and the Committee on Community Policy agreed. “This is consistent with the goals of the Smith Design for Institutional Diversity approved by the board of trustees in October 1988 to make Smith an institution of higher education that values diversity, promotes civility, and combats racism,” Riddell explained.9 At the all-college meeting on May 1, 1989, President Dunn announced the cancellation of afternoon classes on a day the following fall for the college to focus on community education regarding “racism and diversity.”10 This day became known as Otelia Cromwell Day.

1Joseph Berger, “Deep Racial Divisions Persist In New Generation at College,” New York Times, 22 May 1989.

2Proactive efforts to address racism and other forms of discrimination include the strategic plan Toward Racial Justice and work guided by the National Association of Diversity Officers in Higher Education (NADOHE) framework to advance racial equity. Training of students, staff, and faculty in various arenas including the following can also be ameliorative: Everyday Tools for Equity and Inclusion and Leaders for Equity-Centered and Action-Based Design (LEAD).

3Marjorie Richardson, “A Record of Racist Notes,” spring 1993, pp. 2–3, Black Students’ Alliance records, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00308, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

4Ibid., p. 3. For a history of responses including “Celebration of Sisterhood” and “The Quad Vigil of 1992,” see Juli Grace, history, Celebration Records, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00326, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

5Bethany Spooner, “Otelia Cromwell Symposium Neglects Issue of Anti-Semitism,” Smith College Sophian, 16 Nov. 1989, p. 1.

6“Smith College Civil Rights Policy qtd. in Dennis Hudson, “Report on the Smith Design,” 28 Jan. 1993, p. 1, Self-Study records, College Archives,CA-MS-01059, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

7Marilyn Schuster, “Report on the Fund for a More Inclusive Curriculum,” June 1990, qtd. in Hudson, p. 9.

8SOAR, “Summary of Activities for 1990–1991” qtd. in Hudson, p. 7.

9Debra Bradley, “Racism and Diversity are Subjects of Symposium,” 31 Oct. 1989, p. 1, Office of College Relations records, College Archives, CA-MS-01050, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

10Ibid.

The Otelia Cromwell Symposium on Racism took place on November 9, 1989. The event program described it as a “special day of talks, workshops, films, and entertainment, in honor of Smith’s first known African American graduate, Otelia Cromwell, class of 1900. The symposium continues the college’s efforts to combat racism and to create a diverse and multicultural community.”11

Riddell chaired the first Cromwell Day committee, which included 11 staff and faculty members and six students. President Dunn invited Student Government Association President Farah Pandith ’90 to serve along with students from the following organizations: Asian Students’ Association, Black Students’ Alliance, International Students’ Organization, Korean Students of Smith, Nosotras, and South African Students of Smith.12

It was President Dunn’s decision to name the day after Otelia Cromwell. She wrote in a memo to Riddell on August 9, 1989, “As you perhaps know, Otelia Cromwell was the first African American to graduate from Smith, and it seemed to me to be a good idea to name our conference for her.” Susan Nowlan AC ’94, a student at the time, confirmed in a March 29, 1994, interview with Dunn that it was the president’s goal to connect the day “to our own history, in order to make a clear statement that Smith had been racially diverse for a long time.” And further, “that the education of women of color was something of long-standing importance at Smith College.”13

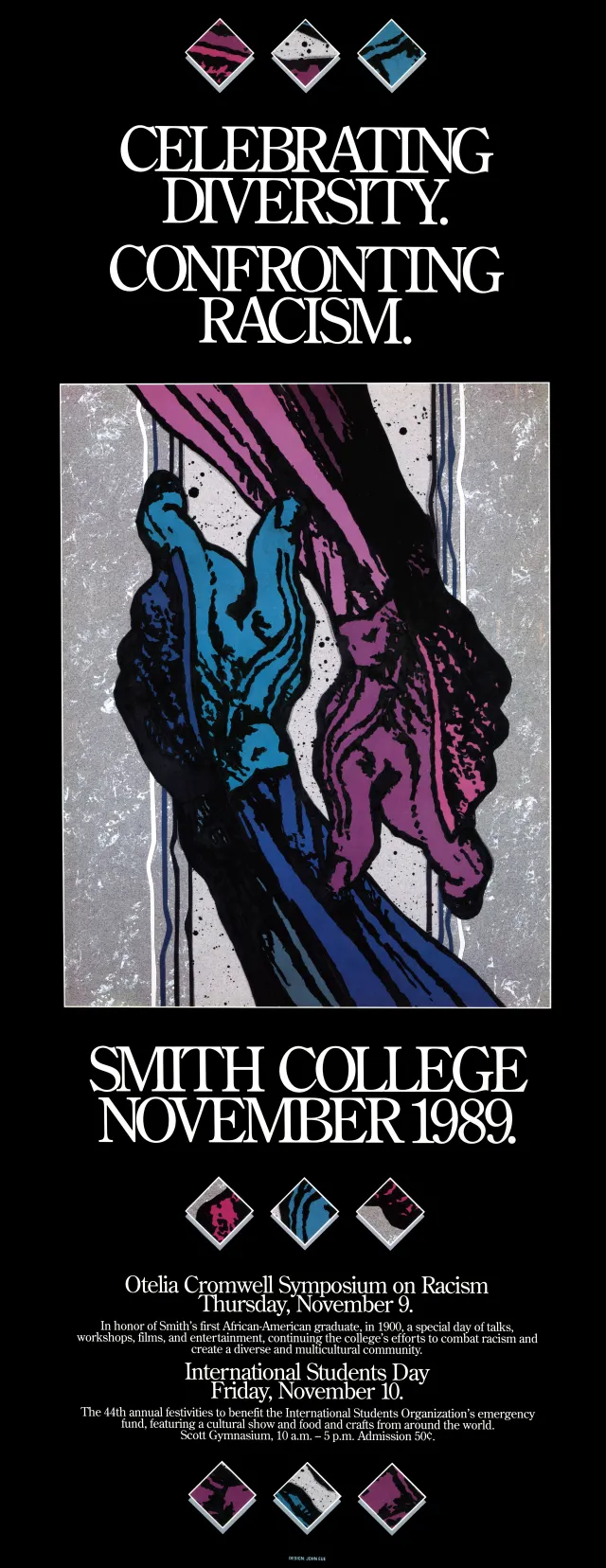

Initially, the committee considered inviting a keynote speaker. Notes from September 18, 1989, list novelist Maxine Hong Kingston, writer and civil rights activist Maya Angelou, journalist Connie Chung, attorney and activist Elaine Jones, and author Paule Marshall as possibilities.14 Instead, the committee decided to host a panel of Smith-affiliated speakers. The “keynote session,” which took place in John M. Greene Hall, featured President Dunn in conversation with students, faculty, staff, and alums on “The State of the College: Celebrating Diversity, Confronting Racism.”15 Professor Taitetsu Unno, who participated on the planning committee and panel, suggested the tagline “Celebrating Diversity, Confronting Racism,” which also graced the poster for the day, designed by John Eue of College Relations.16 Panelists answered Dunn’s questions about their own “personal observations of racism” and whether racism can be “reversed by education.”17

Workshops focused on an array of topics, including Black athletes, the “many faces of Latinas,” Asian Americans as the so-called model minority, educator Jaime Escalante’s efforts to teach calculus in Los Angeles, Guatemalan immigrants, “the American Indian,” and the incarceration of Japanese Americans during World War II. At an evening session, President Dunn offered “An Assessment of the Otelia Cromwell Day Symposium.” Students, staff, and faculty then had the opportunity to attend three performances: an Indian classical dance featuring Ranjanaa Devi, a stand-up comedy routine by Phil Nee, and a jazz concert by Semenya McCord. Refreshments were served at 10 p.m. in the Gamut.

In the days following the symposium, Dunn and Riddell received several notes of appreciation from students, staff, and faculty. They also fielded two notable critiques. Some members of the community faulted the planning committee for not addressing antisemitism. Riddell apologized and said that “the lack of a workshop on antisemitism was an error of omission … especially in the wake of the discovery of antisemitic graffiti in the Smith College bookstore” earlier that fall.18 On a more personal note, Adelaide Cromwell ’40—Otelia Cromwell’s niece, a fellow alum, and Smith’s first Black faculty member—took issue with the use of her aunt’s name. In a letter to the Smith Alumnae Quarterly in spring 1990, she wrote, “I am enthusiastically supportive of any endeavor to combat racism at Smith College or anywhere else, but I cannot for the life of me understand why that must be tied to the life of Otelia Cromwell, simply because she was Black.”19 Adelaide Cromwell wanted her aunt to be honored as “a scholar and an exceptional teacher” in her own right. Over the years, more has been done to celebrate Otelia’s accomplishments, including the creation of a video about her life and legacy, and Adelaide attended many subsequent Cromwell Days in person. Planning committee notes from April 30, 1991, reported that Adelaide “now gives her consent to using her aunt’s name.”20

11Otelia Cromwell Symposium on Racism program, 9 Nov. 1989, box 182, folder 8, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

12Memo from Jane Pafford to Mary Maples Dunn, 21 Jul. 1989, box 182, folder 8, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts. For Farah Pandith’s account of her role in the first Cromwell Day, see her essay “Light in Times of Darkness,” Smith Quarterly, 18 Aug. 2025, https://www.smith.edu/news-events/news/light-times-darkness.

13Susan Nowlan, “Otelia Cromwell Day: A Question of Celebration,” 1994, p. 7, Student papers and theses collection, College Archives, CA-MS-01113, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

14Cromwell Committee meeting notes, 18 Sep. 1989, box 182, folder 8, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

15Otelia Cromwell Symposium on Racism program, 9. Nov. 1989.

16Cromwell Committee meeting notes, 18 Sep. 1989. Note that College Relations is now known as Communications and Marketing.

17Mary Maples Dunn, notes for the Otelia Cromwell Symposium Panel, 9 Nov. 1989, box 182, folder 8, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

18Bethany Spooner, “Otelia Cromwell Symposium Neglects Issue of Anti-Semitism,” Smith College Sophian, 16 Nov. 1989, p. 1.

19Qtd. in Nowlan, pp. 18.

20Karen Pfeifer and Mary Martineau’s notes for the Otelia Cromwell Planning Committee, 30 Apr. 1991, box 182, folder 10, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

In 1989, however, the nature and promise of future Cromwell Days was far from settled. On a Dec. 8, 1989, typewritten memo to the planning committee, Riddell scribbled a simple question: “Repeat it?”21

For guidance, President Dunn turned to the Committee on Academic Priorities (CAP) and the Committee on Community Policy (CCP). Composed of eight professors and three administrators—two of whom were nonvoting—CAP was charged with reviewing “the curriculum and the policies of all administrative and faculty committees in matters of educational policy.”22 Populated by students, staff, faculty, alums, and Northampton community leaders, the CCP’s mandate was to “encourage diversity, free intellectual inquiry, and responsible attitudes toward the large issues of the day.”23 The committees deliberated among their own members and consulted others on questions of timing and scope: Should the event be held annually or every other year? Should it take place in the fall or be combined with Rally Day during the spring semester? Should the focus be on racism or should it be expanded to include other forms of discrimination?

CAP recommended that Cromwell Day take place every other year and be combined with Rally Day.24 The CCP advised an annual fall event of expanded scope. A memo to President Dunn formally explained, “The observance should emphasize the companion themes of (1) resisting discrimination in all of its forms and (2) celebrating diversity in all of its forms. We intend by this recommendation that the spirit of Otelia Cromwell Day will embrace the full range of discrimination and diversity acknowledged by the college’s Civil Rights Policy and Nondiscrimination Statement, without losing the concerns and goals of racial and cultural diversity specified by the Smith Design for Institutional Diversity.”25

On Nov. 16, 1990, President Dunn communicated to the CCP that “the plan to put Otelia Cromwell Day and Rally Day together isn't working … too many objections.” She did, however, request that Cromwell Day take place in the spring.26 Dunn accepted the recommendation to broaden the scope of the program. Hence, that academic year’s Cromwell Day took place on Feb. 12, 1991, and focused on “building a community characterized by an appreciation for differences in race, class, religion, and sexual orientation.” Like the first Cromwell Day, this one featured a panel discussion. Workshops focused on broad topics such as issues of oppression, religious pluralism, classism, homophobia, and heterosexism. A concert by the Harlem Spiritual Ensemble closed the day.27

At its debriefing meeting on April 30, 1991, the CCP recognized that “The first Otelia Cromwell Day was organized as a response to student demands for a mandatory class in racism after episodes of racial harassment which occurred on campus. There was some concern that last year’s program was too broad-based and should return to a symposium exclusively dealing with the issue of racism.”28 Meeting notes also recorded a suggestion to rename the day because it “no longer deals exclusively with racial issues.”29

Ultimately, the CCP decided to retain the name unless Dunn objected, and recommended that Cromwell Day be observed annually in the fall.30 The Oct. 3, 1991, celebration featured a keynote speech by linguist, educator, and actor Doris Leader Charge (Lakota) on “Preserving and Transmitting Native American Culture.” Workshops covered topics with titles such as “A Puerto Rican Reading of West Side Story,” “Perspectives of a Lesbian Alumna,” and “A Jew and a Gentile in Dialogue: Being Allies for Each Other.” The evening performance starred actor and director Ossie Davis and actress Ruby Dee, who blended “music, poetry, and dramatic readings interpreting the history of the ‘minority’ experience in America.”31

Alas, racist incidents did not abate. From 1990 to 1992, students received several more notes, a decapitated doll, and a table tent calling them “trained canines of color.”32 Over the years, Cromwell Day continued to focus on understanding and confronting racism, though the aperture sometimes expanded. What had been a symposium “on racism” in 1989 became a symposium “on diversity” in 1993.33 In 1997, the planning committee chose the theme “Language and Communication Across Cultures,” and in 1998 the college invited local schoolchildren to attend a Cromwell Day on “Celebrating Children Across Cultures.” The 1998 program declared, “For more than a decade, Otelia Cromwell Day has been instrumental in challenging our community to think critically about the meaning of cultural pluralism in our society. We have confronted issues of racism, discussed the meaning of culture, and celebrated the traditions of many.”34

The Cromwell Day planning committee has always included students (drawn from Unity Organizations with the assistance of the Office of Multicultural Affairs), staff (fulfilling essential functions and offering staff perspectives), and faculty (chosen in consultation with Faculty Council). Over time, the administrative leadership moved from the Committee on Community Policy to the Office of Minority Affairs to the Center for Religious and Spiritual Life, and eventually, to the Office for Equity and Inclusion. Occasionally, leaders from other units have been called to chair in times of need. For instance, Dean of the Smith College School for Social Work Marianne Yoshioka led the committee in 2018.

Typically, the Cromwell Day Committee begins its work each March by assessing the campus climate and trying to anticipate what the community might need by November. Deciding on a theme usually precedes identifying a keynote speaker. For instance, in 2022, the college’s renewed focus on racial literacy led to the theme “Ignorance Is Not Bliss: The Necessity of Teaching and Learning About Race.” Crystal Fleming, the author of How to Be Less Stupid about Race and now a professor at Smith, addressed this theme directly in her keynote speech. Recognizing the impact of the Israel-Palestine conflict in 2025, the committee invited Farah Pandith ’90, an international diplomat known for her bridge-building work.35

Through the years, Cromwell Day speakers have represented many different fields of expertise and held diverse identities.

Despite earlier requests, the decision to cancel classes all day to make time for expanded programming did not happen until 2020.36 Beginning that year, the planning committee scheduled wellness events in the morning such as “rest to rise” programs by Professor Benita Jackson, poster sessions to share data from campus climate surveys, and updates on equity and inclusion work at Smith, as well as other workshops. Plenary sessions continued to take place after lunchtime; workshops were offered in the afternoon; and artistic performances ended the day. Since then, Smith has continued with a daylong schedule of programming.

21Memo from Tom Riddell to the Otelia Cromwell Symposium on Racism Planning Committee, 8 Dec. 1989, box 2, Tom Riddell papers, College Archives, CA-MS-01191, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

22Code of Faculty Governance at Smith College, Aug. 1989, p. 8. https://www.google.com/url?client=internal-element-cse&cx=013060085753386553107:qfvmbgt-eim&q=https://www.smith.edu/sites/default/files/media/Documents/Provost/Code_of_Faculty_Governance.pdf&sa=U&ved=2ahUKEwi1i5_17pqSAxXxGVkFHXS0Jw8QFnoECAMQAQ&usg=AOvVaw3iXc8j_A0-oLxU4jL_-pR0&arm=e&fexp=121491260,121491258

23Committee on Community Policy, “Report to the Smith Community on Efforts to Promote Racial Awareness,” Apr. 1987.

24Memo from Robert Merritt to Mary Maples Dunn, 2 May 1990, box 182, folder 9, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

25Memo from the Committee on Community Policy to Mary Maples Dunn, 28 Feb. 1990, box 182, folder 10, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

26Memo from Mary Maples Dunn to Pat Skarda and Bob Merritt, 16 Nov. 1990, box 182, folder 9, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

27Otelia Cromwell Day program 12 Feb. 1991, box 182, folder 9, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

28CCP notes by Karen Pfeifer and Mary Martineau, 30 Apr. 1991, box 182, folder 10, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

29Ibid.

30Ibid.

31Otelia Cromwell Symposium program, 3 Oct. 1991, box 182, folder 10, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

32Richardson., p. 5.

33Otelia Cromwell Day Symposium program, 2 Nov. 1993, Center for Religious and Spiritual Life records, College Archives, CA-MS-1057, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

34Otelia Cromwell Symposia program, 1–3 Nov. 1998, box 45, Center for Religious and Spiritual Life records, College Archives, CA-MS-1057, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts.

35The planning committee for Cromwell Day 2025 heard, particularly from students, that our choice of Pandith as keynote speaker missed the mark. Though about a hundred community members engaged with her in a question-and-answer opportunity following the plenary session and some apologized for walking out ahead of her speech, a subsequent town hall organized by and for students indicated that more conversation is needed. To that end, I was gratified that the leaders of the town hall, Salma Baksh ‘28 and Karolina Suarez Aldarondo ‘28, met with me, presented notes, suggested actions, and listened to my brief account of the origin and purpose of Cromwell Day. They asked me how can more members of our community better understand the history and evolution of this longstanding tradition. In the spirit of transparency and shared learning, and in consultation with President Sarah Willie-LeBreton, I spent the two months in the College archives researching and drafting this account of the history of Cromwell Day.

36Summary minutes of the Committee on Academic Policy, 18 Apr. 1990, box 182, folder 9, Office of the President Mary Maples Dunn Files, College Archives, CA-MS-00073, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts; memo from CCP to Mary Maples Dunn, 28 Feb. 1990, folder 10; and memo from CCP to Mary Maples Dunn, 20 Feb. 1992, folder 11.

Naming the day after Otelia Cromwell continues to anchor Cromwell Day as a reflection on the transformative power of education and diversity, as well as a celebration of Black excellence. Otelia herself went on to earn a doctorate in English from Yale University. She authored important books on Thomas Heywood and Lucretia Mott, and edited Readings from Negro Authors. Since Adelaide’s death in 2019, Cromwell Day has honored her legacy as Smith’s first Black faculty member and her accomplishments as co-founder of the African Studies Center at Boston University and author of The Other Brahmins: Boston’s Black Upper Class, 1750–1950.

At Cromwell Day in 2009, poet Nikky Finney debuted “Maven,” a three-part poem that delves into Otelia Cromwell’s characteristics as a daughter, scholar, and writer, praising her dignity, sagacity, and fierceness. “We herald your bright hallmark of firsts,” Finney writes in reference to Cromwell’s identities as the first Black graduate of Smith and the first Black woman to earn a doctorate at Yale. The poem does not directly address Cromwell’s encounters with racism, such as the fact that she boarded with Professor Julia Caverno downtown rather than on campus with other students—an arrangement that reflected unspoken but certain exclusion. Neither does it mention Cromwell’s advocacy on behalf of Carrie Lee, class of 1917, who, unlike her, was explicitly denied on-campus housing. Thanks to Cromwell and the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Lee was eventually assigned a room in Albright House. Finney’s poem alludes to these and other challenges that Cromwell faced and overcame with the line “You gray beautifully—but early.”37

Cromwell Day also honors Black history with the recent tradition of singing “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” usually performed by the student group Blackappella as part of the plenary session. Written by brothers James Weldon Johnson and John Rosamund Johnson, the song has sustained activists in the struggle for liberation since 1900. Sometimes known as the Black National Anthem, “Lift Every Voice and Sing” gained renewed prominence and national use after the murder of George Floyd in 2021. The struggle for liberation benefits, of course, from broad participation. Timothy Askew, the author of Cultural Hegemony and African American Patriotism: An Analysis of the Song, “Lift Every Voice and Sing,” explains that the Johnsons wrote the song without reference to a specific racial identity and addresses all Americans. Marc Lamont Hill, a CUNY professor of urban education and ethnic studies, adds, “It’s a black national anthem, but it’s also a quintessential American song because of its message of fighting for freedom.”38

In keeping with Cromwell Day’s original tagline to both confront racism and celebrate diversity, Cromwell Day continues to uplift overlooked histories. In 1989, the identities of other Smith graduates from various backgrounds were not well known. To remedy this lack of awareness, President John Connolly asked College Archivist Nanci Young to identify some of these early graduates in 2001. Since then, the college has honored the following alums with a slideshow carousel in the Goldstein Lounge, as the namesakes of the Friedman Apartments, and as the photographic subjects of a gallery titled “Our Predecessors: Smith’s Earliest Graduates of Color” in Seelye Hall:

This portrait gallery is another step in meeting student requests for increasing awareness of alums of color and their accomplishments. As psychologist Claude Steele’s research shows, the presence or absence of environmental cues—such as building names and portraits of people who look like you—can affect one’s sense of belonging.39 No college of its age, including Smith, was designed for the diversity of students, staff, and faculty of today. Hence, we must reflect on our past and present in order to build a more just and inclusive future.

37Nikky Finney, “Maven,” 2009, https://www.smith.edu/news-events/events/cromwell-day#:~:text=2009%20Ni…

38Liane Membis, “Professor at historically black college questions 'black national anthem,'” CNN, 2010, https://www.cnn.com/2010/LIVING/07/21/black.national.anthem/index.html.

39Claude Steele, Whistling Vivaldi: How Stereotypes Affect Us and What We Can Do (New York: Norton, 2010), p. 145.

Cromwell Day was never meant to stand alone in the college’s efforts to address racism. From the beginning, students, staff, and faculty demanded systemic change: a process for hearing grievances and holding people accountable, sustained leadership around issues related to equity and inclusion, and a diverse curriculum. Smith has made progress on all of these desiderata—in the adoption of a Civil Rights Policy, the establishment of both the Office for Civil Rights Compliance and the Office for Equity and Inclusion, the adoption of the strategic plan Toward Racial Justice, and the development of many new courses and hiring of new professors focused on “the study of world cultures and American cultures beyond the traditional focus on Western Europe and white America.”40 But the work is incomplete and must continue.

In addition, the work must be informed by not only our traditions, values, and principles but also the people who live and learn here now. As I wrote in my 2025 reflection, “Transformative Inclusion at Smith College”:

I have given much thought to the question of how one could define the term “inclusion.” For instance, inclusion could mean conformity—that is, requiring an individual to meet a dominant standard in order to earn belonging from a central power. We might call this provisional inclusion. Another kind of inclusion, however, would enable individuals to bring their whole selves into an ecosystem—say, a college—and their contributions would be welcomed as a way to change the ecosystem itself. We might call this transformative inclusion, which expects that every student, faculty, and staff member will transform the institution—not merely assimilate into it.41

The conversations sparked by Cromwell Day—then and now—remind us that learning and dialogue are always unfinished. They ask something of us: curiosity, care, concern, courage, and a willingness to sometimes sit with discomfort. Yet, they are also our greatest strengths because they affirm our commitment to honoring the full diversity of our community, knowing that by doing so we become—as President Sarah Willie-LeBreton has said—”better scholars, teachers, and humans.”42

If you have input for the Cromwell Day planning committee, please email oei@smith.edu.

40Hudson, p. 9.

41Floyd Cheung, “Transformative Inclusion at Smith College,” Smith Today, 21 Mar. 2025, https://www.smith.edu/news-events/news/transformative-inclusion-smith-college

42Sarah Willie-LeBreton, Remarks to Alumnae Association Board of Directors, Fall 2025.

Themes & Speakers

| Year | Theme | Speaker(s) |

|---|---|---|

| 2025 | Courage and Community in Contentious Times | Farah Pandith ’90 |

| 2024 | Now What?: Liberation in the Midst of Uncertainty | Tourmaline |

| 2023 | Finding Joy on Our Journey to Racial Justice | Brittany Cooper |

| 2022 | Ignorance Is Not Bliss: The Necessity of Teaching and Learning About Race | Crystal Fleming |

| 2021 | Collective Imagining of Anti-Racist Democracies: Fighting for Racial Justice | LaTosha Brown |

| 2020 | Tackling Anti-Blackness: Moving Past the Abstract | Yamiche Alcindor (virtual) |

| 2019 | Acknowledging Injustice and Practicing Anti-Racism | Deborah Archer ’93 |

| 2018 | Healing and Resistance Through Community | D-L Stewart |

| 2017 | Resist, Act, and Persevere | Roxane Gay |

| 2016 | Advancing Change: The Responsibility of Higher Education in Times of Crisis | Sonia Sanchez |

| 2015 | Incarceration: Intersections of Criminal Justice | Dawn Porter |

| 2014 | Stand Up, Raise Your Voice | Michele Norris |

| 2013 | The Journey from Civil Rights to Social Justice | Julianne Malveaux |

| 2012 | Social Justice, Activism, and New Media | Latoya Peterson |

| 2011 | Race, Identity, and Research Across the Disciplines | Harriet Washington |

| 2010 | Inequality and Disparities in Education | Thelma Melendez de Santa Ana |

| 2009 | Thinking Through Race at Smith College | College presidents and alumna panel |

| 2008 | Dialogues Across Difference | Majora Carter and Luma Mufleh ’97 |

| 2007 | The Arts in Color | Aaron Dworkin |

| 2006 | Science, Race, and Society | Vernice Miller-Travis |

| 2005 | Race, Class, and Social Justice | Gary Orfield |

| 2004 | Politics, Participation, Power: The Challenges and Possibilities of Democracy and Diversity | Lani Guinier |

| 2003 | Living for Change: Reflections on the Civil Rights Movement | Grace Lee Boggs |

| 2002 | Race Matters | No keynote; various lectures |

| 2001 | The Politics of Culture: Appropriation, Appreciation, Interrogation | No keynote; various lectures |

| 2000 | How Race Is Lived in American Institutions | No keynote; two symposia on reparations and in publishing |

| 1999 | American Pluralism and the Civic Culture | Lani Guinier |

| 1998 | Celebrating Children Across Cultures | Mary L. Ford |

| 1997 | Language and Communication Across Cultures | Johnnetta B. Cole |

| 1996 | Racism and the Production of Knowledge | Pearl Cleage |

| 1995 | The Paradox of Integration: The Complexities of Racial Change in America | Orlando Patterson |

| 1994 | No theme | Gayle Pemberton |

| 1993 | Minorities in Higher Education | Juliet Garcia |

| 1992 | No theme | bell hooks |

| Nov. 1991 | No theme | Doris Leader Charge |

| Feb. 1991 | Building a Community Characterized by An Appreciation for Difference in Race, Class, Religion, and Sexual Orientation | Panel moderated by Frances Volkmann |

| 1990 | No symposium held | |

| 1989 | Celebrating Diversity, Confronting Racism | Keynote session with a community panel of students, faculty, staff, trustees, and administrators |

[Source: Cromwell Day programs, Box 211, Folder 36, Office of College Relations records, College Archives, CA-MS-01050, Smith College Special Collections, Northampton, Massachusetts; and Special Days records, Box CA Shared 65, Smith College Archives, CA-MS-00110, Smith College Special Collections, Smith College Archives, Northampton, Massachusetts.]

More About the Cromwells

About Otelia Cromwell

Born in Washington, D.C., in 1874, Otelia Cromwell (class of 1900) was the first of six children born to Lucy McGuinn and John Wesley Cromwell, a journalist, educator and the first African American to practice law with the Interstate Commerce Commission. Otelia Cromwell’s life and work were characterized by a deep sense of justice and responsibility toward others.

After graduating from the Miner Normal School, Otelia Cromwell taught in the Washington, D.C., public schools for several years. She transferred to Smith College in 1898 and graduated in 1900. She returned to teaching for a number of years and then resumed her education, receiving a master of arts from Columbia University and a doctorate from Yale University in 1926; Cromwell was the first African American woman to receive a Yale doctorate. She soon became professor and chair of the department of English language and literature at Miner Teachers College in Washington, D.C.

Cromwell remained at Miner Teachers College until her retirement in 1944. A distinguished scholar and teacher, she authored three books and numerous articles including Readings From Negro Authors, for Schools and Colleges, the result of collaboration with Eva B. Dykes and Lorenzo Dow Turner. It was one of the first collections of its kind. She received an honorary degree from Smith College in 1950.

After her retirement from teaching, Cromwell accomplished her most significant scholarly work, The Life of Lucretia Mott, the Quaker abolitionist and women’s rights activist. It was published in 1958 by Harvard University Press and continues to be cited by contemporary scholars. Cromwell passed away in 1972 at the age of 98.

About Adelaide Cromwell

Adelaide Cromwell ’40 was the first African American professor appointed at Smith. After teaching at the college, she served for more than 30 years on the sociology faculty at Boston University. There she co-founded the African studies program in 1953 and founded the Afro-American studies program in 1969, the first graduate program in the country in that field.

Adelaide Cromwell was also a leader and activist in Africa, convening the first conference of West African social workers in Ghana in 1960, and serving on a commission to assess the state of higher education in what was then called the Belgian Congo. A member of the executive council of the American Society of African Culture, the American Negro Leadership Conference in Africa and the advisory council on Voluntary Foreign Aid, among others, she also maintained active membership in the Council on Foreign Relations and a number of professional organizations.

She is the author of several books, including Unveiled Voices, Unvarnished Memories: The Cromwell Family and Slavery and Segregation, 1692–1972, and An African Victorian Feminist: The Life and Times of Adelaide Smith Casely Hayford, 1868–1960.

Cromwell earned a master’s degree in sociology from the University of Pennsylvania and a doctorate in sociology from Radcliffe College. A recipient of the Smith Medal in 1971 and an honorary degree in 2015, she was the niece of Otelia Cromwell, class of 1900. Adelaide Cromwell passed away in 2019 at the age of 99.

Confronting Challenges. Creating Change.

Through individual and community engagement, we reach hearts. Through inclusive education and programming, we nourish minds. Through institutional change and collaborations, we realign systems. Since its beginning, Smith has been at the forefront of envisioning a world where we all belong. Cromwell Day gives us an opportunity to reflect upon our accomplishments and look ahead to all that we can still do to evolve and transform. Every voice matters, and every step—whether large or small—makes a difference.

2025 Committee Members

Floyd Cheung, Davis Rivera, Carolyn McDaniel, Erica Banz, Shawn Reming, Jessica Masiero, Kim Alston, L’Tanya Richmond, Cristina Guevara, Queen Lanier, Raven Fowlkes-Witten, Uchechi Anaba ’27, Yendry Cabrera ’27, and Ange Carla Joseph ’26.

Smith Voices: Progress & Possibilities

Linda Smith Charles ’74

“We certainly wanted to make sure that the institution understood our needs as Black women on this campus ... I found Smith, in hindsight, really doing its best to try to accommodate the needs. They didn’t know what to do, but were certainly willing to listen ...”—On student activism, in an interview for the Alumnae Oral History Project.

Sylvia Lewis ’74

“... I think what Smith learned was about how they should embrace change, or can embrace change, and that it really is good, and will be something that would be very impactful and very positive for the future generations.”—On the formation of the African American Studies Program, in an interview for the Alumnae Oral History Project.

Ryan Rasdall ’11

“... I think the campus was moving in the right direction of trying to grapple with this and understand, Why did this happen? What can we do to be more supportive? To be a better — make people feel safe on our campus?”—On the atmosphere on campus after a racist incident, in an interview for the Alumnae Oral History Project.

Celebrating Otelia Cromwell

For the 2021 Cromwell Day convocation, the Smith community created an inspiring digital quilt. “The Life and Legacy of Otelia Cromwell” was created as part of the college’s 25th annual Cromwell Day celebration honoring Smith’s first African American graduate.

“Maven” by Nikky Finney

Smith College commissioned poet Nikky Finney to compose a poem in honor of Otelia Cromwell. She debuted “Maven” in 2009. Hear Camille Ollivierre ’20’s recitation at the 2019 ceremony (starting at 21:20).

Read “Maven”

For Otelia Cromwell, 1874–1972

GENUS: DAUGHTER

"When you are a thinking woman neither violence or sugar plums can muzzle the power of thought."

Imagine, hatch, comprehend, apprehend:

Know the inside and the out. You are just

a girl when your mother dies. Left to tend

the rest of the flock, you, the oldest,

the one most like your father, taught

to leave no stone unturned, marry thrift

and industry, while burying your head

in the stacks. Sang-froid but never

silent. Inquire, picture, ponder, think

over, think and think, again. Giddy

with your own mind, "Master everything"

is the family crest, no veil feigning, faking,

guise, masquerade, or fanfare. There is

a right way and a wrong. When you give

your hand to the world, your responsibility:

To have a mind, keep in mind, change

a mind—and be the last to die.

GENUS: SCHOLAR

"An educated group is a thinking group."

Intuit, divine, check and recheck, invent:

Know the backward and the forward.

You care nothing for the popular, even

less for the slipshod. Your arms flower

with all the leading out books, choosing

wisely what and who trains you: Frankness,

virtuoso, mastery, crackerjack. Think and

think, again. You leave college and university

exceptionally prepared. You are complex

and astute, as calm as a comma. No time

for jewelry or parlor beaus. There is

a gold watch, a signet ring, a Smith

College pin: White letters on gold just

above the heart. Diligent, proficient, self-

possessed, you weigh in with words, to state

your tolerance to the inefficient. You never

back down from what is right. Young Adelaide

is your "dependable" and the 9th graders

leaning in to your instruction whisper: This

must be college. You gray beautifully—but early.

GENUS: WRITER

"The genius does not write to please."

(nor live to marry)

Veritas. Words pulled through a fine-tooth

comb, then, before sleep, pulled through,

again. You refuse to segregate language from

life, read German for sport and swing golf

clubs just to stay on the qui vive. You write

of the legality of taxes, pica out democracy,

vow and edit for the integral Negro intellectual.

Winnow, probe, sift through, quest: Think

and think, again. Solemnly engaged now to

Lucretia & Thomas, you dislike being called

"Dr." and remain forever keen on "Miss."

What the dutiful trained hand can perfectly

stitch delights you. Unconventional and easy-

going, your desire never wanes: To be put

through the paces, edify, enlighten, to work

outward—from simple seam to monogram.

We herald your bright hallmark of firsts,

those sprightly high-waisted truths; the soft-

spoken whippersnapper, eloping still.

All words in italics are the words of Otelia Cromwell.

©2009 Nikky Finney.