‘I Want Them to Fall in Love with Learning’

Alum News

Published December 3, 2020

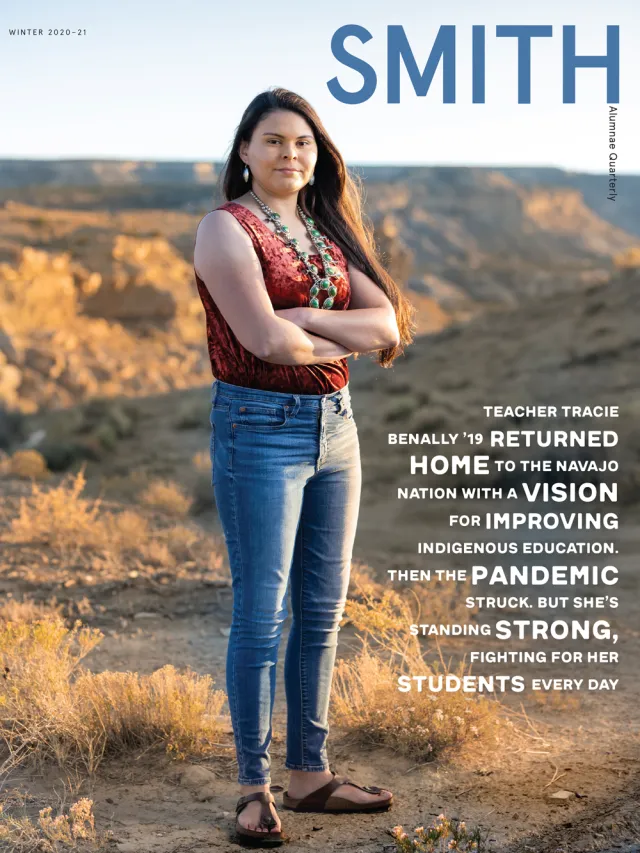

In mid-August, I received an email from a former student with the subject line “Greetings from a second-year teacher.” From that cheery start, I could hardly have anticipated the depth of the challenges that Tracie Benally ’19 would go on to describe about her work as a teacher on the Navajo reservation in New Mexico where she grew up.

“I’m teaching ELA [English and language arts] at the high school I graduated from,” Tracie wrote in that first correspondence. “It’s been, honestly, one of the greatest gifts life has offered me. But I won’t sugarcoat it; it’s extremely challenging. Teaching in the age of coronavirus has taught me a lot about how educators are treated, particularly here on the Navajo Nation.”

By early June, the Navajo Nation had more cases of coronavirus per capita than any state in the country. Indeed, according to emerging statistics at that point, if Native American tribes were counted as states, the five most-infected states in the country would all be Native tribes, with the state of New York dropping to number six. Poverty, scant resources, limited internet and cell phone connections and restricted access to medical support have all conspired to ravage the community in which Tracie teaches.

As her professor and adviser, I knew she had come from an underresourced high school. At Smith, though, I watched her blossom into her potential, and I also witnessed her growing activism and commitment to increasing educational opportunities in her community.

Following is a conversation with Tracie about the challenges and rewards of teaching at Crownpoint High School, and the ways in which Tracie’s Smith College education has influenced her perspective on her work, her future and her commitment to make change.

Did you always plan to become a teacher and to give back to your community?

Did you always plan to become a teacher and to give back to your community?

For as long as I can remember, I’ve been drawn to teaching. My grandmother was an elementary school teacher when she passed, and I inherited her classroom supplies. It wasn’t until I was in 10th grade that I actually felt it was possible for me to not only become a teacher, but also to come home to my community as a leader, to be a source of support and representation for my people. In high school I learned that schools, particularly those in communities of color, should be responsive to community needs and hopes. Smith helped me connect academic terms such as “socioeconomic status” and “educational inequity” to my real-world experiences.

In my culture, we do not use the term “vision” lightly. I believe it is a sacred word that encapsulates the historical, the present and the future of a community’s education. As a teacher, this term drives both my hopes for and frustrations with public education. While the desire to be a positive educator remains strong, I often feel drained and overwhelmed at the prospect of battling a system that is doing exactly what it was intended to, which is to assimilate and fail Indigenous students. Even so, I do my best to harness the power of my community’s vision for our áłchíní [children] and persist.

What do you mean when you say the system intends to assimilate and fail Indigenous students?

It’s important to understand that there is a clear distinction between Indigenous education and Indian education. Indigenous education, I think, is not only culturally responsive, but is led and sustained by community members; this is how education, as a whole, has been taught for centuries. On the other hand, Indian education is a term coined by the U.S. government. When physically removing families from their homelands and murdering my ancestors didn’t work, the government turned to boarding schools, a more insidious method of extermination. When considering what it means to fail Indigenous students, I don’t think one could ever fully understand this statement without acknowledging the roots of white supremacy, land-grabbing and assimilation tactics that were inherent in the boarding school system. Children were kidnapped from their homes, abused for simply existing and taught to internalize a deep hatred for their selves.

Chiricahua Apache children arriving at the Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, 1885 or 1886. Photograph courtesy of the Library of Congress

How do you see that playing out today?

There are four main areas I take issue with.

First, many of our schools are quite literally falling apart, we have little to no access to technology or wireless internet, many of our roads aren’t paved for school buses to access students and we often have to scramble to make do with the few resources we do have.

Second, there isn’t enough opportunity for parents, guardians, students or teachers to weigh in on designing a curriculum reflective of the values and perspectives of culture and community, which makes it difficult to find relevancy in the material students are being taught, especially in history, language arts and science.

“When physically removing families from their homelands and murdering my ancestors didn’t work, the government turned to boarding schools, a more insidious method of extermination.”

Third, there is little to no data, especially updated data, when it comes to Indigenous students. It’s difficult to understand how to fight the issue when we can’t make quantitative connections between graduation rates, dropout rates, funding, household income, etc. I took a class with Katherine Kinnaird [Clare Boothe Luce Assistant Professor of Computer Science and of Statistical and Data Sciences] my senior year, and it changed my entire perspective on the significance of data when it comes to creating spaces for social change.

And finally, in my educational journey, grades K–12, I only had four Native teachers and I never had a Native administrator. I think representation in educational spaces is deeply tied to student outcomes, especially when one considers the reality that Native communities experience extremely high teacher and administrative turnover rates.

As a high school student from the Navajo reservation in rural New Mexico, how did Smith appear on your radar?

When I was 16, I applied to a Native American/Native Hawaiian/ Alaska Native pre-college program called College Horizons. There, I was surrounded by fellow Indigenous students and an ocean of admissions officers from top-tier schools who taught me about admissions processes, college entrance exams and personal statements. I felt nervous at the prospect of being a first-generation college student; [apart from my teachers] no one I knew had ever graduated from college. At the college fair, I scoured the crowds for a friendly face until I found Sid [Sidonia] Dalby [Smith’s associate director of admission] tabling for Smith. She was incredibly warm and encouraging, and that one conversation had me hooked. Having been raised by generations of strong, intelligent Indigenous women, I knew I wanted to spend my college career on a campus with similar values. By the start of my junior year of high school, I was so set on attending Smith that I used a blank wall in my childhood room like a canvas, writing inspiring quotations and achievements I had found from Smith alumnae.

What hurdles did you face in applying?

Most high school students have access to resources like extracurricular activities and various AP classes. I had to work to make opportunities where none existed. I established an after-school ACT/ SAT study program for students at my high school; I scrubbed toilets and tutored middle school students to save money for SAT/ ACT study guides so I could tutor myself. I scoured the internet for tools to strengthen my vocabulary, my test-taking skills and my critical/analytical thinking skills. There were many times I begged my mom to drive me two hours from home to our nearest bookstore so I could purchase and read classics I’d never been taught.

What was it like when you arrived at Smith?

My transition to Smith was rough, to say the least. I struggled with basic skills: how to write well, how to think analytically and critically. Until I got to Smith, I didn’t know that I could question literally everything! I’m often asked if I experienced a culture shock arriving on campus. Maybe in some ways I did. There was, of course, the lack of Indigenous representation on campus and the privileges I noticed classmates taking for granted. But more than anything, I felt a sense of shock that, for the first time in my life, I had an abundance of educational resources at my disposal. For the first time in my life, I was in true control of my education: I could decide what classes I wanted to take, what professors I wanted to study with and how I wanted my education to benefit me.

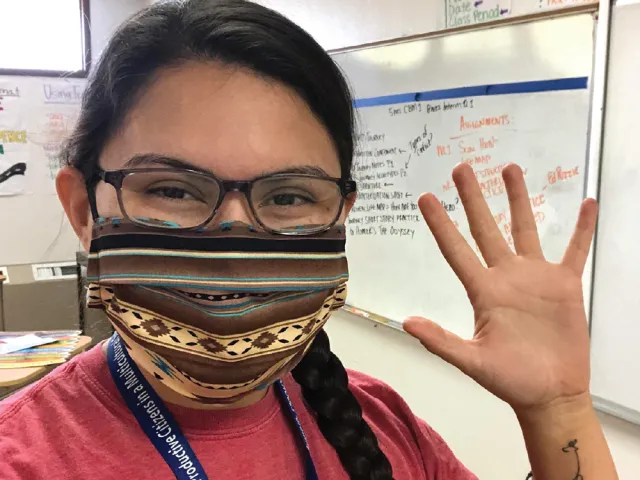

Tracie Benally ’19 shown in her classroom at Crownpoint High School in New Mexico.

Once the pandemic forced the schools to close, you say you became deeply concerned about the mental and physical health of your students. Can you speak about that?

The Navajo Nation is about 300,000 people, with half of them living on a reservation the size of West Virginia. I teach in a school district that has 34 schools and covers thousands of square miles. In March, my district, in compliance with New Mexico Public Education Department orders, closed schools. This decision shook our students and community. Suddenly, nearly 300 students no longer had a place where they could feel safe, have access to secure food or communicate with their classmates or teachers about their fears, worries and stressors. Teachers were told not to have contact with students, except those with individualized education programs. Due to limited internet access, students were sent “learning packets,” which could hardly compensate for the loss of instruction yet were our only choice.

What are some of the classroom challenges you have faced, before and since COVID-19?

[Before COVID-19] the main issues included consistent attendance, constant testing, pacing during a given class period and managing social-emotional wellness with few mental health resources. [Now that we’re meeting] online I confront all of the same issues, but we also battle the added layer of lack of access to the internet. Most of my students do not have wireless internet at home, nor do they have cell phone reception. It is difficult to engage students when they need mental health resources, when their families are struggling and when it is difficult for them to find a ride to the nearest Wi-Fi location or signal for their wireless hotspots that our school district provided.

“I want my students to be afforded the same opportunities I had at Smith: like they are in control of their education. I want them to see themselves as change-makers in their own communities.”

What do you wish for your students, your school and your community?

To nurture my community’s vision, I deeply wish that our school was tribally and community controlled. I wish that we had a full-service community school where we had washers, dryers, clothing and a pantry available for students. I dream of a school where students can delve into expeditionary learning and can venture outside and learn from our elders about our land and its history, our cultural stories, songs and language. My students deserve an approach that genuinely centers and celebrates their identities, and that helps them fight systemic inequities that have sought to extinguish who they are.

I want my students to be afforded the same opportunities I had at Smith: like they are in control of their education, with well-resourced schools where there are counselors and other mental health professionals. I want them to see themselves as change-makers in their own communities. Most of all, I want them to fall in love with learning.

You told me you have a student, a junior, who you’d like to apply to Smith.

Yes, I do! She’s so wonderful. She’s worlds ahead of who I was when I was a junior. One of my favorite conversations to date was about Indigenous solidarity with Black Lives Matter, and how to make her classmates more aware of systemic injustice. She’s amazing. I wish that you could meet her. I showed her the Smith website, and she’s already started thinking about her application. I really hope she applies.

Rosetta Marantz Cohen is the Myra M. Sampson Professor of Education and Child Study and Elizabeth Mugar Eveillard 1969 Faculty Director of the Lewis Global Studies Center.

This story appears in the Winter 2020-21 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Delivering Relief, Maintaining Connections

“As the pandemic persisted, I felt an enormous hole in my heart,” writes Tracie Benally ’19. “I couldn’t sleep knowing that families were suffering from a lack of resources in our supply chain.” She describes stores with little food, no soap products or disinfectant and no toilet paper. “I knew I had to do something,” she says. Between May and September, Benally and a couple of friends launched a pandemic relief fund that raised around $35,000, which they used to provide food boxes, disinfectants, adult and baby diapers and other essentials to more than 300 families. “I spent my days driving hundreds of miles, delivering supplies and talking to families about how they were managing,” Benally says. “Some of these households were the homes of my students, and this is how I was able to maintain a sense of contact and continue to care for them.”

Photograph by Gabriella Marks