Altered States of America

Alum News

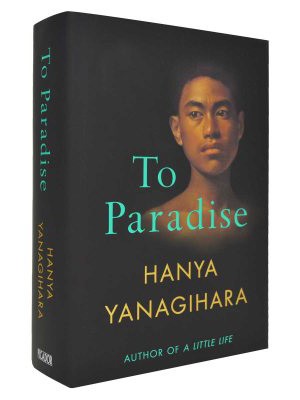

In her epic new novel, To Paradise, bestselling author and New York Times editor Hanya Yanagihara ’95 reimagines U.S. history and, in the process, offers a complex critique of culture, humanity, love, and country.

Published March 28, 2022

“When you move around a lot, you become a good observer and your life depends upon being able to fit in, being able to communicate with other people, understanding the rituals of it,” says Hanya Yanagihara ’95.

The writer and editor spent her childhood bouncing between Hawaii, New York, California, Maryland, and Texas, eventually landing at Smith College before moving back to New York City for good. The result of this peripatetic upbringing: “You start approaching any new context like an anthropologist would,” says Yanagihara.

That observant, anthropological view has helped define not only Yanagihara’s fiction, but also her work as editor-in-chief of T, the style magazine for The New York Times, where she celebrates the worlds of fashion and art, travel and design.

Back in 2015, Yanagihara, who majored in English at Smith, attained cult literary status thanks to her second novel, A Little Life—a complex story about friendship and suffering. The book follows the postgraduate lives of four friends who meet in college and have a heart-wrenching journey toward middle age. It was shortlisted for the Booker Prize, became a finalist for the National Book Award, and still evokes outpourings of grief. (Just type in the hashtag #ALittleLife on TikTok and you’ll see.)

Now, Yanagihara is making headlines again with her latest novel, To Paradise, which was published in January to much acclaim. The New Yorker devoted almost 7,000 words to the author and her work (calling it “complex and iterative”), while USA Today labeled it “a novel of the highest order.”

Now, Yanagihara is making headlines again with her latest novel, To Paradise, which was published in January to much acclaim. The New Yorker devoted almost 7,000 words to the author and her work (calling it “complex and iterative”), while USA Today labeled it “a novel of the highest order.”

To Paradise—an epic read at more than 700 pages—weaves together three novellas, each taking place 100 years apart in the same townhouse in Greenwich Village. The characters live through wildly altered versions of America. The first part, which takes place in 1893, is a gay twist on the Henry James novel Washington Square, making same-sex marriage legal in much of the country. The next section, set in 1993 during the AIDS epidemic, documents the romance between a lawyer and his young boyfriend, a descendant of Hawaiian royalty. Finally, the book fast-forwards to 2093 to tell the story of an apocalyptic New York City that has been ravaged by a pandemic and climate change.

Just weeks after the release of To Paradise, Yanagihara called in to share her inspirations, the questions she asks when writing, what she remembers most from her time at Smith, and how she seemingly does it all.

The timing of your coverage of post-pandemic America is remarkable. When did you start writing the book?

I started thinking about it in 2016, researching it in early 2017, and writing it in early 2018. By research, I mean I talked to some scientists at Rockefeller [University], as well as a scientist at a group called the EcoHealth Alliance in New York, which focuses purely on zoonotic illnesses. All of those doctors predicted that we were due for something and said that we were ill-prepared and ill-equipped because the United States and the world had not put enough money into virology and immunology research. But in 2017 they seemed fairly certain something was coming. They didn’t put a date on it, obviously, but by the time we actually got sent home in March of 2020, I was deep into the narrative—about halfway through the third part, which is set in the pandemic. The book that resulted was not informed by COVID.

Once COVID hit, did the book change?

Nothing really changed. In fact, it felt like very separate events: the events of the book and the events that were happening outside. If anything, it was comforting to have a project that I was quite deep into already and a project in which I was master of that particular universe. In retrospect, it probably gave me a great sense of comfort, being able to have a world in which I was able to determine the outcome in such a confusing context.

Because of your research, did you feel a different sense of what was going on than most people?

I had a doctor to talk to who was very reassuring and not an alarmist. He had worked on many different pandemics and understood the long view and the importance of not panicking the population. I remember him predicting that we’d be back to normal in 2022. And I thought, “God, he’s really being melodramatic here—2022?” But of course, it looks like he’s going to be correct.

So you started thinking about the book in 2016. Did the presidential election help inspire it?

Specifically, it was the Muslim ban. I think that was a moment many of us felt that the country as we knew it was changing in real time. Of course, the country’s always changing, but the breaks with tradition made me rethink this idea of America as a paradise. A paradise is not meant to welcome everyone—it’s meant to keep people out. I wondered, “Had the way we conceived of America all along been somehow erroneous, or had it been an incorrect metaphor?” Of course, America is a paradise for so many people, still, and has been for so many—including my ancestors and the ancestors of most people in this country, who had the choice to immigrate. I started thinking about these questions of what a society will do to protect itself. The idea of nation as heaven or as refuge.

If you were writing the book right now, would you change the concept at all?

I don’t think so. But I do think it was born out of a certain moment, even though I couldn’t have predicted the moment. One of the questions that the book asks is a question that many of us are asking now. Namely, “Is America a country?” The sentence “America is a country of sin at its heart” repeats in all three sections of this book. Is that sin something that is foundational? Elementally, is America so damaged that you can’t do anything but start again? Or are the systems damaged but can be repaired within the framework that exists? Those sorts of questions that the book asks are some of the conversations that will define how we think of ourselves as a country moving forward.

You also have a big job at The New York Times. How do you manage it all?

I’m not someone who feels that they need to write every day. But I would not have finished this book had we not been sent home. You gain an hour by not commuting every day. You gain back your nights. You’re not going out to dinner. There was a lot of extraneous time that I suddenly got to reclaim. I also think I’m very good at time management. And when you have less time—as anyone who has a job or a child or some other all-involving work will tell you—you start using those remaining hours much more carefully.

“Had the way we conceived of America been somehow erroneous, or had [calling it a ‘paradise’] been an incorrect metaphor?”

The title of the book, To Paradise, made me think of Smith. Did it have anything to do with Paradise Pond?

It’s funny, I didn’t even think about that until you mentioned it. But I should have lied and said “Yes,” but no, it didn’t.

What inspired you to go to Smith?

I was all set to go somewhere else, then I went on a tour. At the time, I was besotted with Sylvia Plath [class of 1955], and it seemed like a very romantic gesture to go to Smith as a tribute, in a sense. I had gone to a very large, private high school in Hawaii that felt, at the same time, very cozy. Smith felt the same way. I loved the museum and its collection of art. And I liked the fact that I didn’t have to take a core. Some of those are better reasons than others, but that’s why I went.

What did you love about Smith?

One of the small, overlooked things about the campus that I did really value, in a strange way, was the plant life. Growing up, my family had always gardened and I had always appreciated flowers, but it was a completely different set of flowers and plants. Being at Smith gave me a different understanding and appreciation for the landscape and the botany of the East Coast than I expected going in.

How about the professors at Smith?

What was special and different was that you never were taught by a teaching assistant. You had professors who were always available to you. [English professor] Douglas Patey was my adviser. And I had [emerita professor of history and American studies] Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, as well as [English professor] Craig Davis. These were scholars who were aware that along with trying to teach us how to think critically and read critically, they were also engaged in the task of trying to make us adults. It’s not something that you really appreciate at the time: You appreciate it later.

You graduated from Smith in just three years. What was that like?

I came in with extra credits and took extra classes every semester, except my last one. Partly it was financial, but I was also impatient. I wanted to become an adult and move to New York. If I had the chance to do it again, I would’ve stayed that fourth year and taken more courses in subjects that I would never have studied again. For many students, it’s the last time you’ll engage with science or politics or math or literature—and it is a privilege to be able to do that.

Laura Begley Bloom ’91 writes for various outlets, including Forbes and Tripadvisor. She is the former editor-in-chief of Yahoo Travel and deputy editor of Travel + Leisure. She is a frequent contributor to the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

This story appears in the Spring 2022 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Illustration by Stuart Patience