Stories We Carry With Us

Alumnae News

Published June 14, 2018

Inclusive Casting Seems True To L’Engle’s Spirit

By Martha Southgate ’82

“Life, with its rules, its obligations, and its freedoms, is like a sonnet: You’re given the form, but you have to write the sonnet yourself.” These words from Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time are spoken to the protagonist, Meg Murry—but they might as well have been spoken to Ava DuVernay, the director of the recent film version. When DuVernay read those words in preparing for the film, it seems that she took the spirit of them utterly to heart.

DuVernay has been writing her own sonnet for years. In a surprisingly short time she has risen from film publicist (she didn’t attend film school) to lauded and sought-after filmmaker, always forging her own path through the male-dominated business of big-budget filmmaking. The budget for A Wrinkle in Time was more than $100 million, making it the most expensive film ever helmed by a black woman. And it was sufficiently successful that it’s led her to another big-budget gig, directing the comic book film The New Gods.

All this makes DuVernay the most successful black woman filmmaker ever, but beyond budgets, what I find thrilling about her success is what she has done and is doing in terms not only of representation, but of bringing women and people of color into the filmmaking system. This dates from her very earliest days, when she formed ARRAY, a collective devoted to distributing and sharing films by and about people of color.

As DuVernay’s star has risen, her commitment hasn’t wavered: Not only does she put diverse faces on the screen, she builds up—and sometimes revives—careers for women and people of color in all aspects of the film business. She hires only female directors to work on Queen Sugar, the show she executive

produces for the Oprah Winfrey Network. Among them are Julie Dash, director of 1991’s Daughters of the Dust, the first nationally distributed film directed by an African American woman, and Patricia Cardoso, director of 2002’s Real Women Have Curves. Notably, both these directors had early successes and then found themselves shut out of other work in the business. In addition to hiring new faces, DuVernay knows about the closed door for some veterans and, with them, is forcefully pushing it open.

Aside from her work behind the camera, DuVernay cast L’Engle’s heroine Meg Murry as a biracial girl, played by Storm Reid, and surrounded her with a racially diverse cast that includes Mindy Kaling, Oprah Winfrey and Reese Witherspoon.

When I saw the film, it was Reid as Meg whom I found most moving. I was once 13, brown-skinned, bespectacled, a bit awkward. And I never saw anyone like me in the movies—especially as the hero of the tale. To see this young woman gradually come into her own strength and grace—well, it would have meant a lot to me then. It meant a lot to me now, at 57.

And just as L’Engle’s Meg captivated and empowered generations of little girls (and boys, too), so does DuVernay’s inclusive vision—and hard work—broaden what’s possible, no matter who the viewer is. Madeleine L’Engle was a great believer in possibility. No doubt, she would approve.

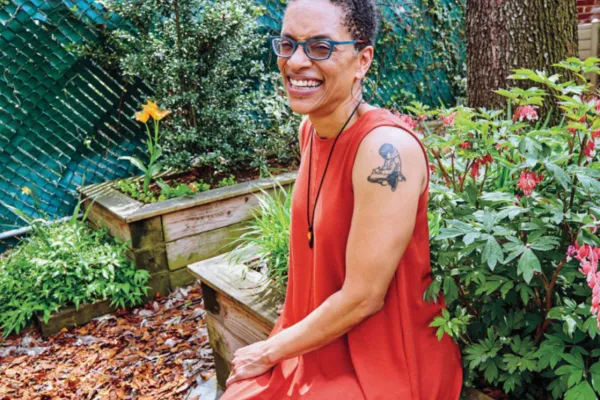

Martha Southgate ’82 is the author of four novels, most recently The Taste of Salt.

Girls - And Love - Can Change the World

By Betsy Cornwell ’10

The saving grace at the end of A Wrinkle in Time is love: not love as an abstract concept, but something so real, tangible and active that Meg Murry believes she could grip it in her hands if only she knew where to reach. The ideal of love as activism suffuses all of L’Engle’s extensive body of work. It comforted me as a child reader, and it inspires me now, as a feminist, a teacher and a writer of young-adult fiction.

In seventh grade, I gave a presentation on Madeleine L’Engle for a “role models” project in social studies class. I remember my voice breaking and my eyes tearing up as I told my smirking peers that “she makes it OK for a girl to be smart, for a girl to be strange.” Her heroines, especially Polly and Flip, felt like real, flawed friends as well as aspirationally smart and strange young women. Through her characters and her own life, Madeleine L’Engle embodied the kind of writer and woman I hoped to become.

Later, I applied to Smith largely because of two strong alumnae: L’Engle and my great-aunt Lola, whom by then I felt I knew almost equally well. It was likely arrogant to feel any intimacy at all with the famous writer, but surely L’Engle would agree with fellow luminary C.S. Lewis that “we read to know we are not alone.”

Also like Lewis, L’Engle was a devout Christian who saw faith and the creative life as deeply entwined. She discusses her Christianity explicitly in her nonfiction, like the wonderful A Circle of Quiet, and it comes through in the Time quintet through figures like Proginoskes the cherubim in A Wind in the Door and the biblical setting of Many Waters. But even when I was in the most reactionary throes of my teenage atheism, her books didn’t alienate me.

I am agnostic now, but I say with great respect that L’Engle is one of the most Christian writers I’ve ever read. There is nothing evangelical or exclusionary in the spiritual aspects of her work; it is rooted in humility and a deep desire to lift up and serve those who most need help.

I can easily trace my interest in LGBTQ+ activism to reading A House Like a Lotus, long before I identified as part of that community myself. And my still deeply held conviction that a girl can change her life and the fate of her world for the better? That’s L’Engle’s ethos through and through. Her books taught that children, especially girls, can and do save the world.

I think often of her instruction to authors: “You have to write the book that wants to be written. And if the book will be too difficult for grown-ups, then you write it for children.” She never talked down to her young readers, and I’d call that part of her activism; I strive now, in my own writing, to make it part of mine.

L’Engle’s books have been a source of love-as-action for me all my life. I can only hope that my books further the ideals of service, kindness and fierce intelligence that I have no doubt she foster—as I did—at Smith.

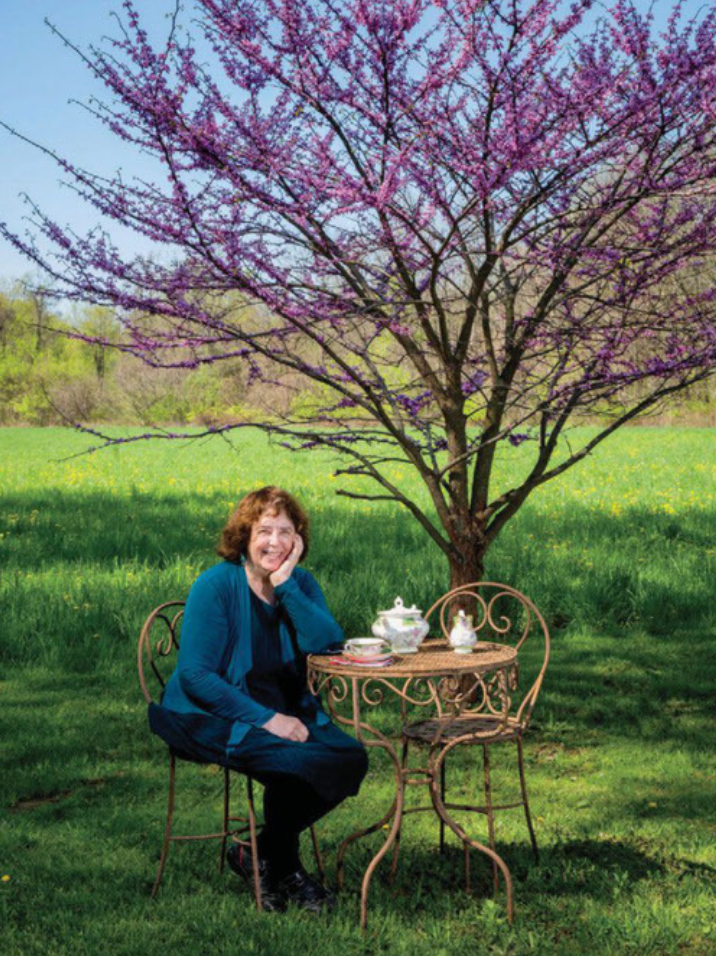

—Betsy Cornwell ’10 has written several young-adult novels, including Mechanica and Venturess. Her forthcoming book, The Forest Queen, is a feminist retelling of Robin Hood.

Photograph by Tess Harper Molloy

Verse for a Fellow Writer

By Jane Yolen ’60

The circumstances of this poem began when I was partway into what turned out to be seven years of teaching a children’s literature course at Smith for the education department. Madeleine L’Engle ’41 was coming to campus to give a lecture at John M. Greene Hall, and then to attend a more intimate Q&A at an Alumnae House tea party. I was drafted to be her guide.

Over the years, we became part-time correspondents; she blurbed one of my books. Not exactly good friends, but not strangers either. I have not seen the recent Wrinkle in Time movie, though I wonder what her reaction would have been. She did speak her mind on such things.

Spirit Guide: Madeleine L’Engle

Like Virgil, she led many

through her particular Paradiso,

walking through the sloughs

of adolescent despond.

Her words warmed the fires

of millions of young hearts,

calling them to vocations

of service and discovery.

I led her once, and she followed,

through the nuances of our old college,

along the unchanged paths

of Paradise, past the new buildings,

the charters of the once-changed

into the nuance of new.

She spoke in the great hall

where her words fell like grace.

We ended at the white house

alums had built. There a tea party

for her avid readers was spread.

Students sat, sprawled, knelt before her,

eager to hold their hands out

to her consistent flames, their questions

quicker than her answers

as she parsed each meaning.

One eager girl announced

in breathless wonder:

“Once I could fly down the stairs

without ever touching a step.”

Virgil left science behind,

the wrinkles in that particular time

gone in an instant, bending

to the questioner’s passion.

Leaning like a saint,

toward that whisper of a girl,

Madeleine answered without doubt,

without irony, only with a certainty:

“I could do that, too.”

In one short line, she left metaphor for faith,

changed memory to mimesis,

leaping across an abyss of belief

where I could never follow.

It was a river of faith

where one either flew or swam

without fear of depth or of drowning.

One false thought, and you are gone.

Jane Yolen is the author of 365 books, including poetry, books for children and novels for young adults.

Photograph by Jessica Scranton

Photograph by Brian Smale

L’Engle’s Voice Reaches Across Time

By Ruth Ozeki ’80

The first deliberate lie I ever told was about time. I had just turned 8, and my parents had given me my first watch. It was a Timex, with a round analog face and a little dial on the side that you needed to wind every day. This gift was a big deal. It meant I was old enough to be responsible for keeping time and telling time and being on time. It meant I was growing up.

The mechanics of the watch I mastered quickly, and I realized two things: one, that I could wind the hands backward; and two, that this could be useful. Time was malleable! The first time I tested this premise, I was playing outside and wanted to stay, so I wound back the hands on my watch and came in 10 minutes late for dinner. My heart was racing as I told my lie—But Mom, my watch stopped!

It worked, and I grew bolder. Ten minutes became 15, then 20. Inevitably, I went too far, nudging back the hands until I lost track and entered into a fictional timescape of my own creation, where everything that had been real was relative and unreliable. Then my mom took the watch away.

A year or so later, when I read A Wrinkle in Time and learned about tesseracts, I felt a jolt of recognition. I was right. Time was relative, and malleable, too. I just had to learn to navigate it better.

A Wrinkle in Time was one of those seminal books in my life, as it has been in the lives of many awkward girls who feel like geeky outsiders—by which I mean all girls, all of us. When we’re young, we create our childhood mythologies from the books we read, and this book was central to mine. Around the time I first read it, my father had a heart attack that almost killed him, and he disappeared into the hospital for a very long time. The Wrinkle in Time that I read was a story about a young girl with an adored but mysteriously absent father; confronted with his fallibility, she must overcome her disappointment and anger, and learn to rely on herself in order to save him.

Other girls read different Wrinkle(s) in Time. I asked four of my friends about how this book shaped their childhood mythologies, and I got four different responses. The first friend read a book about a girl who has to protect her mother. The second friend read a book about a girl who bravely resists uniformity and social control. The third read a book about her beloved kid brother. And the fourth, who had a distant mother, read a book that was all about Aunt Beast.

What all our books had in common was a smart, brave girl with lots of faults, who learns to accept herself. We all read a book that empowered us and gave us hope that we could change terrible things, and we all read a book about the power of love to effect this change.

A novel is a kind of tesseract, an act of tessering readers into timescapes outside their own. As a novelist, I am aware that I am speaking to readers who exist outside my own time and space, and are possibly not even born. Writers tell time. That’s what Madeleine L’Engle, who died in 2007, is still doing today. Like Mrs. Whatsit, she is still speaking across time, tessering into the lives of young girls today, and then tessering them back out with her, into her magical world. May she continue.

Ruth Ozeki ’80 is a novelist, Zen priest and professor of English at Smith. She is the author of four books, including A Tale for the Time Being.

This story appears in the Summer 2018 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Learn More

The Making of Madeleine L’Engle

Before she wrote A Wrinkle in Time, the late author, class of 1941, developed a literary ambition that drove her to aim for the stars, and to not give up. That’s one insight awaiting scholars when her extensive papers come to Smith.

14 Things to Know about Madeline L’Engle’s Life and Legacy

Fun facts to consider as we celebrate the 100th anniversary of this world-famous author's birth.

‘Tale of a Smart, Awkward Misfit’

Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wrinkle in Time has influenced generations of readers with its mix of adventure, science fiction, spirituality, family devotion—and a memorable heroine. Alumnae tell us it opened their hearts and minds to unimagined possibilities and quite literally changed their lives.

Martha Southgate ’82. Photograph by Beth Perkins