Democracy in Distress

Research & Inquiry

Published August 1, 2022

What is democracy? This seemingly simple question has a seemingly obvious answer: It means, literally and etymologically, that the people rule themselves. But this straightforward reply leads to a tangle of thorny questions: How, exactly, are the people meant to rule themselves? What institutions and procedures enable the people’s rule? Are there limitations on the exercise of popular power—on what the people can elect to do?

And who are “the people,” anyway? Who counts as a member of the polity, and who decides?

These questions, unresolved and fundamentally unresolvable, have been central to the history of democracy. They have, in some sense, been the very content of that history, making “democracy” less a concrete thing—a single regime type, stable over time and clearly identifiable as, simply, “a democracy”—than a set of ongoing disputes over the messy politics of self-rule.

Along the course of this history, one of the major fault lines of democratic dispute has been over democracy’s relationship to equality, on the one hand, and domination, on the other. Democracy, which entails the political equality of those who rule, has often been closely associated with the domination of those who do not. In the early United States, democracy meant rule by propertied white men—property that included enslaved persons and land stolen from Indigenous peoples, and rule that included command over women. Popular sovereignty and equality among white male citizens was widely believed to be both consistent with, and dependent on, these forms of domination.

Yet this was never the only vision of democracy: Then, as now, the marginalized, the colonized, the excluded, and the dominated fought back and offered their own visions for what ruling ourselves might look like, what peoplehood might entail. They gave their lives to abolish slavery, to build a public schooling system, to extend the voting franchise, to control the conditions of work, to assert bodily autonomy and sexual agency, to live lives free from violence and oppression, and to partake in political power and public freedom on equal terms.

To say that contemporary U.S. democracy is in distress, then, is to note how this fault line is again active—destabilizing institutions, upending norms, and bringing into question once more who “the people” are and how they should rule. New assaults on reproductive and voting rights, attempts to censor and ban books considered “critical race theory,” attacks on transgender people, migrants, and racialized minorities—tying all these efforts together is the idea that democracy, properly construed, is equal rule by some over and against others. These efforts are echoed and amplified by right-wing movements worldwide.

Yet hope remains: Democracy need not mean the domination of some for the benefit of others. Multitudes are again mobilizing against these assaults and in pursuit of an expansive vision of democracy that enables and ensures lives of dignity and abundance for all.

Democracy is in distress, but it is not yet clear what the outcome will be and what new futures may yet unfold.

Erin R. Pineda is an assistant professor of government at Smith. She teaches courses in the history of political thought, democratic theory, race and politics, social movements, and American political thought. She is the author of Seeing Like an Activist: Civil Disobedience and the Civil Rights Movement (Oxford University Press, 2021).

This story appears in the Summer 2022 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Democracy in Distress

A Special Series

Introduction by Erin Pineda

What is democracy? This seemingly simple question has a seemingly obvious answer: It means, literally and etymologically, that the people rule themselves. But this straightforward reply leads to a tangle of thorny questions: How, exactly, are the people meant to rule themselves? What institutions and procedures enable the people’s rule? Are there limitations on the exercise of popular power—on what the people can elect to do?

PART 1: My Body, But Not My Choice by Andrea Cooper ’83

Navigating a post-Roe world with Candace Gibson ’07 of the National Latina Institute for Reproductive Justice and Genevieve Scott ’06 of the Center for Reproductive Rights.

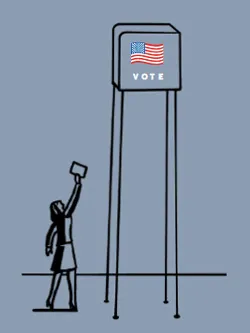

PART 2: Block the Vote by Andrea Cooper ’83

Voter suppression laws are on the rise. But Smithies are fighting back, working to expand political participation by eliminating ballot restrictions and empowering disenfranchised voters.

Illustration by Anthony Russo