Understanding the Zika Virus: An Interview With Professor Steven Williams

Research & Inquiry

Published February 26, 2016

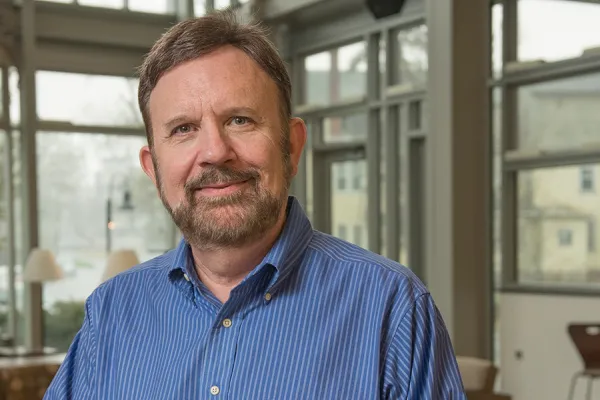

Steven Williams, Gates Professor of Biology and Biochemistry at Smith, has been studying the molecular biology of parasites for decades. Mainly focused on eradicating the world’s neglected tropical diseases, Williams and his researchers have recently turned their attention to the Zika virus amidst an outbreak of the mosquito-borne disease.

Williams’ lab is now working on developing a molecular test to screen mosquitoes for Zika based on the virus’ genetic material.

In recent months, the Zika virus has made headlines following reported cases in at least 32 countries and territories. In the U.S., the federal Centers for Disease Control (CDC) has issued travel warnings for pregnant women in response to increasing concerns regarding the virus’ potential effects on fetal health. (In Brazil, Zika has been associated with cases of microcephaly—babies born with abnormally small heads—although that link has yet to be scientifically proven.)

The CDC also recently issued a health alert citing three cases of the virus possibly contracted through sexual contact.

Zika has been gaining attention at Smith, as well. Last month, the student organization Voices for Choice (VOX) and the Lewis Global Studies Center hosted a panel of Smith faculty members discussing the virus, global health and the impact on women’s lives.

Here’s what Williams had to say about the science and significance of Zika:

What exactly is the Zika virus?

“It’s called a flavivirus, and it’s pretty closely related to the dengue and West Nile viruses, which everyone was worried about in previous years. They’re a very similar group of viruses, and they’re all transmitted via mosquitoes. Zika is currently spreading quickly throughout the Americas. The first major outbreak of Zika was in 2007 in the Pacific, and in just a few years it’s spread from the Pacific, and to the Americas. And of course there have already been cases in the United States—as of February 17, 82 cases in 21 states, according to the CDC, all infected travelers entering the U.S. There’s no question in my mind that it’ll be circulating further in the U.S.”

What research are you currently conducting here at Smith related to Zika?

“My lab is working on a molecular test to screen mosquitoes for Zika. One of the things we do is develop diagnostic tests for screening both human and mosquito populations for infectious diseases that are mosquito-transmitted. Zika hit our radar a few months ago and we started working on a diagnostic for it. I want to emphasize that we don’t have the Zika virus here on campus. All the work we’re doing to develop the Zika diagnostic is based on the sequence of the RNA genome of Zika. We’re developing a test that detects that sequence. To do that, we don’t actually have to have the virus—it’s all based on computer analysis.”

How big a concern is Zika to people in the United States?

“There’s definitely concern. There are cases of Americans who are living overseas in Zika areas who either know they’re pregnant, or who might get pregnant, and they’re requesting to be transferred or are moving back to the U.S. because of concerns about exposure to the virus. The CDC has warned women who are pregnant or who may become pregnant to be careful about travelling to areas with Zika. But official travel bans are very rare.”

How is the Zika outbreak similar to or different from the recent Ebola outbreak?

“The biggest similarity would be that Ebola had a rapid spread during that last outbreak, and Zika is currently spreading very quickly. Otherwise there isn’t much of a similarity. Zika is actually spreading more rapidly, but it is far, far less dangerous than Ebola. The mortality rate of Ebola was very high. Depending on which outbreak you’re talking about and in which country, mortality could be anywhere from 40 percent to 80 percent—which are ridiculously high numbers. By contrast, almost nobody dies from Zika. I’d say it’s a bit like the flu in that regard. The flu is also a virus—people do die from the flu—but it’s not something that kills people who are otherwise healthy. If you get a severe case of Zika, you would start getting body aches and headaches, a high fever, rash and so on. However, Zika infections can actually be asymptomatic. The only way those people would know they’ve had Zika is through a blood test.”

What is the link between Zika and microcephaly?

“Everyone is saying Zika can cause microcephaly in newborns, but the evidence for that comes primarily from Brazil, where both Zika and microcephaly have seen an increase. There is a correlation—some babies who died have been recently shown to have Zika in their brains. So it is very tempting to say that Zika is causing the microcephaly. That’s likely true, but it has not been proven yet. There are some who believe there may be other factors involved, such as cytomegalovirus and rubella, or so-called German measles.”

What is the next step in your research on Zika?

“We’re hoping to collaborate with colleagues who are in areas with Zika, such as Haiti, so that our test can be tried out in the field. A lot of groups are working on tests for Zika, but they’re really focused on the human side of things and we’re concentrating on screening mosquito populations. It’s very important to know about the mosquito population so that precautions can be taken if necessary. Screening mosquito populations can be a very sensitive indicator of risk to the human population in a given region.”