The Debate Over Transhumanism

Research & Inquiry

Professor of Philosophy Susan Levin examines the ethics of human ‘bioenhancement’

Published June 29, 2021

In her new book, Posthuman Bliss? The Failed Promise of Transhumanism, Susan B. Levin, Roe/Straut Professor in the Humanities and Professor of Philosophy, offers what Bruce Jennings of Vanderbilt University calls a “searching critique of biotechnical fabrication of human thought and emotion on the molecular level.” Here, Levin breaks down the debate over transhumanism, the moral and ethical dilemmas it presents, and its potential implications for society and humanity.

What is transhumanism, and what does it have to do with being human?

Debate over the biotechnological “enhancement” of human beings is prominent today. Within bioethics, the most contentious facet of this debate is advocacy of transhumanism, or “radical” enhancement. Transhumanists urge our dedication to the development of biotechnologies that would secure the advent of “posthumans,” who surpassed human beings categorically, particularly in rational capacity and lifespan.

Transhumanism has both nothing and everything to do with our humanity. For advocates, being human is but a way station on the path to humanity’s self-transcendence. There’s nothing intrinsically valuable about being human. Transhumanists sharply denigrate human capacities. They do so either across the board, when targeting the elimination of our biological capacity to experience anger, grief and sadness, or in their merely human form, as with rational ability. Nothing that transhumanists are willing to grant the status of a flourishing life has yet occurred; nor can it do so, as long as humanity fails to transcend the limits set by its biology. Transhumanists presume that more of a cherished ability is always better, irrespective of contexts in which or that for whose sake it might be deployed—matters that they persistently neglect.

At the same time, transhumanism has everything to do with being human since advocates press us to disinvest in the worth and very idea of humanity’s having a future.

What do readers need to understand about your research and your new book?

Much of the debate over transhumanism has focused on safety concerns and immoral consequences—such as increased social inequality—of the availability of bioenhancement technologies. Contesting transhumanism on this basis matters greatly. But such objections have limited range, for if unsafe and unjust outcomes were addressable through ongoing research, regulation and subsidies, then moral objections to transhumanism might be met.

I saw the need for a fundamental critique of transhumanism, on both philosophical and scientific grounds. Posthuman Bliss? The Failed Promise of Transhumanism contests transhumanists’ views of reason, emotion, the mind, genes, the brain, their problematic handling of ethics, and its troubling implications for liberal democracy. Furthermore, it challenges the “informational” view of reality and knowledge that transhumanists trumpet as The Truth, and on whose veracity they utterly depend to deliver posthumanity.

Transhumanists assert that “society needs a culture of enhancement.” They do, at any rate, since the pursuit of posthumanity would require abundant public funding. Some of what transhumanists dangle before us, especially immortality, may be viscerally alluring, and, absent careful scrutiny and counterbalancing, their fantasy of posthuman bliss could elicit significant public support. Available resources are inevitably scarce, so those allocated to transhumanists’ quest could thereby not be directed to proven, cost-effective measures involving education, air and water quality, and the like.

On intrinsic grounds, transhumanism should be a nonstarter. Combating its visceral allure, however, is a task that requires extensive public discussion, to which philosophers and scientists, among others, can fruitfully contribute.

Though Posthuman Bliss? consists largely of critique, I didn’t want to limit myself to that. My original scholarly field wasn’t bioethics, but Greek philosophy, and I’m still very active in that area. In the final chapter, I bring that background to bear when suggesting how a virtue-centered perspective on living well could fruitfully be adapted to the needs and aspirations of American liberal democracy.

Is transhumanism a concept specific to the 21st century?

This is a fascinating, complicated matter. The closest antecedent may be prior Anglo-American eugenics. Julian Huxley debuted the term “transhumanism.” Ties go well beyond the lexical, however.

Anglo-American eugenicists extolled human agency in a similar fashion, insisting that we dethrone Darwinian selection and bring our development, henceforth, under “rational control.” Further, per the “Geneticists’ Manifesto” of 1939, the potential for biological upgrades of humanity was “unlimited.” Other parallels are evident when we consider what biotechnologies would, allegedly, deliver: a game-changing ability to shape the biological profiles of future beings; the vast heightening of rational capacity and prosocial attitudes; and the diminution, or, better, elimination, of the very capacity for so-called negative, or antisocial, emotions.

What’s more, ethical rationales and their socio-political implications are more alike than meets the eye. Earlier eugenicists were openly utilitarian, trumpeting a moral requirement to maximize populational welfare through bioenhancement and corresponding sociopolitical mandates. When aiming to placate critics, transhumanists tout the idea that decisions about the use of bioenhancement technologies would stem from personal discretion. Indeed, the bulwark of transhumanists’ defense against the charge of substantive ties to prior eugenics is their insistence that their proposal is not merely compatible with, but would strengthen, autonomy.

“Transhumanism has both nothing and everything to do with our humanity,” says Professor Susan Levin.

Yet, when pressing their own agenda, transhumanists make substantial use of utilitarian rationales, and, within utilitarian thought, the worth of personal autonomy is ultimately negotiable. Trans-humanists’ utilitarian argumentation, largely tacit, helps to explain the otherwise puzzling claim that prospective parents are morally required to choose maximal bioenhancement.

Your book is highly interdisciplinary. Is this a function of the topic or your treatment of it?

Bioethics is itself a deeply interdisciplinary field, involving contributions by specialists in philosophy, law, medicine, biology, neuroscience and so on. The debate over radical bioenhancement casts a wide disciplinary net even by these standards. My methodology in Posthuman Bliss? adds a further layer to this, as its engagement with theories and arguments outside my own discipline is more extensive than is typical.

I hadn’t originally intended to delve as extensively as I did into scientific topics. But I found stark, alarming patterns in transhumanists’ approach to science: their unsubstantiated commitment to genes’ strong causal role in relation to complex phenotypic traits, such as intelligence, together with their compartmentalized lens on the mind and brain, which anchored a conviction that particular faculties could be targeted for augmentation or elimination, as the case might be.

These misconceptions about genes and the brain stem from a view of reality and knowledge that centers on information, whose units are, purportedly, isolable and manipulable. Seen by transhumanists as a timeless truth, this stance is a historical construct dating to World War II and its a!termath, one tied closely to cryptology and the rise of computing. Concepts from these domains were extrapolated to human biology—with the aid of metaphors, such as that of “cracking” the genetic “code,” treated non-metaphorically. Similarly, the human brain was framed as a “logical machine.” This orientation, which vastly oversimplifies the evolution, biology and brain of human beings, is on the verge of being outdated.

My recognition that this widening of my project was needed and eagerness to extend it dates, ineffably but no less crucially for that, to my own liberal arts education. What’s more, the environment at Smith, my academic home of nearly 30 years, is deeply conducive to interdisciplinary work and to the interweaving of scholarship and teaching that helped set the stage for Posthuman Bliss?

How do your philosophical and scientific arguments against transhumanism relate to each other?

Even if science and technology could do exactly what transhumanists say, we should have serious qualms about signing on. For they largely presume the veracity of their own, highly contentious and constrictive answers to longstanding questions in Western philosophy about human nature and a flourishing life. Why should we accept their extreme version of rational essentialism, which excludes a necessary role for emotion in a life well lived? Or a view of flourishing that tethers it to maximal capacitation, absent a defense of ends that such abilities might serve, and foregrounds the rational self-sufficiency of posthuman individuals?

For me, philosophical objections to transhumanism ultimately take precedence over scientific ones. But my philosophical and scientific arguments are connected and, in some respects, mutually reinforcing. I argue that, philosophically, a utilitarian lens on radical bioenhancement is deeply problematic. But those of a utilitarian bent should also reject transhumanism: Utilitarians standardly tie our moral obligations closely to measures that science and technology are deemed to make available at a given time; since science and technology strongly undercut transhumanism, moral obligations anchored in these cannot exist.

Philosophical and scientific considerations also come together in my opposition to transhumanists’ handling of “health” and “disability.” They take to an extreme current, worrisome trends, including expansive constructions of “health,” “public health,” and “personal responsibility” for one’s health and that of prospective children; moreover, facets of being human, such as disquiet, are increasingly medicalized. Transhumanists extend medicalization to our very humanity, seen as a “disability” that science and technology not only can, but, morally speaking, must, address.

This story appears in the Summer 2021 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Read More:

Linnea Duley ’16, “The Potential of AI”: Jamie Macbeth, assistant professor of computer science, is studying how artificial intelligence can be used to improve decision-making.

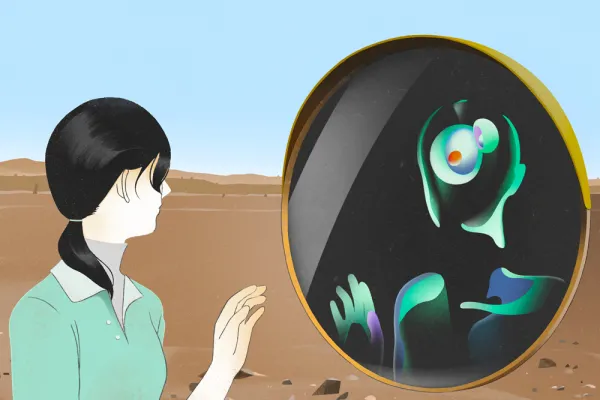

Professor Susan Levin takes issue with transhumanists’ claim that “society needs a culture of enhancement.” Illustration by Ard Su