Raising Anti-Racist Children

Alum News

Talking openly about difference makes it easier to discuss race.

Published September 21, 2020

Recent occurrences of police brutality and racial unrest reflect the continued structural and systemic racism and white privilege that exist within our society.

During the first night of protests and rioting that took place in Atlanta, following the horrific murder of George Floyd by police, I was overwhelmed by the enormity of what was happening. I wrote a poem to express my concerns for my Black son and daughter, Black nephews and nieces, and for innocent Black children, men and women everywhere (see below). Writing the poem was an emotional response that reflected my feelings, my determination and my commitment to not give up and instead fight against continued social injustice in my own way.

As a psychologist and co-author of Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice, I choose to use my knowledge and skills to help parents and caregivers understand the crucial role they play in disrupting the festering sore of racism in our country. My goal is to provide them with the tools they need to challenge the perspective within our society that condones/supports racism and to move forward toward one that does not. The role parents and caregivers play in educating and encouraging ongoing conversations that promote social justice and anti-racism in their young children is crucial to beginning to counteract the pervasiveness of white privilege within our society.

In that regard, through my work, I have engaged in myriad discussions with well-meaning parents who are reluctant to discuss race and racial differences with their children due to concerns about “destroying my child’s innocence” or claims that “young children don’t notice race.” These approaches espouse a “colorblind parenting” approach, in which parents avoid noticing or naming race. Subsequently, their children get the message that race or talking about race is taboo and that racial differences should be ignored.

Research has established that children recognize and are able to categorize race before age 3 and that in-group biases are developed between the ages of 3 and 5. However, research also supports that talking openly about the ways in which we are different and similar, and in developmentally appropriate language, normalizes talking about race and creates opportunities for ongoing discussions as children get older.

Further, societal messages such as “we are all the same” and “justice for all” are confusing to children when discrimination and racial injustice frequently occur and are observed by children. By failing to address these contradictory messages, parents are, in essence, encouraging children to internalize negative messages and/or develop their own explanations for the disparities they have seen. Perhaps, more importantly, parents risk weakening their role in teaching the positive social values and norms that they want for their families.

A preferable approach is “race-conscious parenting,” in which race and differences are openly noticed, named and discussed very early in a child’s life. Race-conscious parenting suggests that you see and comment on race in direct and overt ways. Racial inequities and white privilege are acknowledged as wrong. The historical basis for racism, as well as present-day implicit bias and disparities, are discussed routinely and contextually, using words and situations that children understand. If, for example, your child asks, “Why does that person have brown skin? Why doesn’t he/she take a bath?” try to avoid the colorblind response: “Shh-h, don’t say that. It doesn’t matter; we’re all the same.” Instead, say something like, “He/she was born with brown skin, just like we were born with tan skin. His/her skin is brown because his/her family came from Africa a long time ago, where most people have brown skin.”

By taking this approach, your family will eventually adopt a culture in which inclusion, anti-racism and social justice are the norm.

Children’s books are excellent ways to begin conversations about racial injustice and social problems. For young children, consider books (see my suggestions above) that celebrate diversity with positive roles for characters of all colors, books that build racial pride for minority children and books with themes promoting empathy and kindness. For older children, look at books that address historic and modern-day racism, along with books about adults and children who fought for equality and against bias.

Parents can also prioritize diversity and enrich their children’s lives by engaging in cross-racial friendships, by considering where to live and which school their children will attend. They can ensure that diversity is reflected in the artwork and literature within the home, and children’s participation in age-appropriate racial justice activities, such as peaceful marches, vigils, diverse community service activities and fundraising for social justice causes.

Engagement in social activism cannot erase the profound worry that I sometimes feel about my children’s futures; however, I do feel hopeful when I can inspire parents to tackle racism in words and deeds with their children. It will take all of us working together to eliminate the systemic racism and white privilege that prevents the United States from living up to its ideals.

Illustration by Jonell Joshua

Not as Black in America

By Marietta Collins ’79, 2020

So what is a mother supposed to do? What can I do? How can I go on? I know that “it won’t be okay”, when my heart is broken. My tears continue to fall; my soul begins to wither, and I grieve.

I grieve, anticipating that I will be without my son, without my daughter.

I grieve that racism will render my son or daughter powerless.

I grieve that because racism continues to exist, it continues to threaten their very existence.

I grieve that my son or daughter will cry out for me and I won’t be able to rescue or save them, not because of anything they did, but because racism continues to exist.

However, I refuse to be powerless in my grief. I refuse to be silent. I choose to fight; to fight as I grieve.

I will fight with and for my children.

I will fight with the mothers of children lost.

I will fight with mothers who will grieve and cry.

I will fight for all the children; fight with all the mothers.

I will not give upI will fight against racism

SUGGESTED BOOKS FOR YOUNG CHILDREN

The ABCs of Diversity: Helping Kids Embrace Our Differences by C. Helsel and Y.J. Harris-Smith, Chalice Press, 2020

Not My Idea: A Book About Whiteness by Anastasia Higginbotham, Dottir Press, 2018

The Skin You Live In by Michael Tyler, Chicago’s Children’s Museum, 2005

Something Happened in Our Town: A Child’s Story About Racial Injustice by M. Celano, M. Collins and A. Hazzard, Magination Press, American Psychological Association, 2018

SUGGESTED BOOKS FOR OLDER CHILDREN

The Undefeated by Kwame Alexander, Versify, 2019

A Ride to Remember: A Civil Rights Story by S. Langley and M. Nathan, Abrams Books for Young Readers, 2020

The Hate U Give by Angie Thomas, Balzer & Bray, 2017

Marietta Harvey Collins ’79, M.S.W. ’83, received her doctorate from Emory University. She is a licensed clinical psychologist and associate professor at Morehouse School of Medicine in Atlanta. She is also a New York Times bestselling children’s book author.

This story appears in the Fall 2020 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

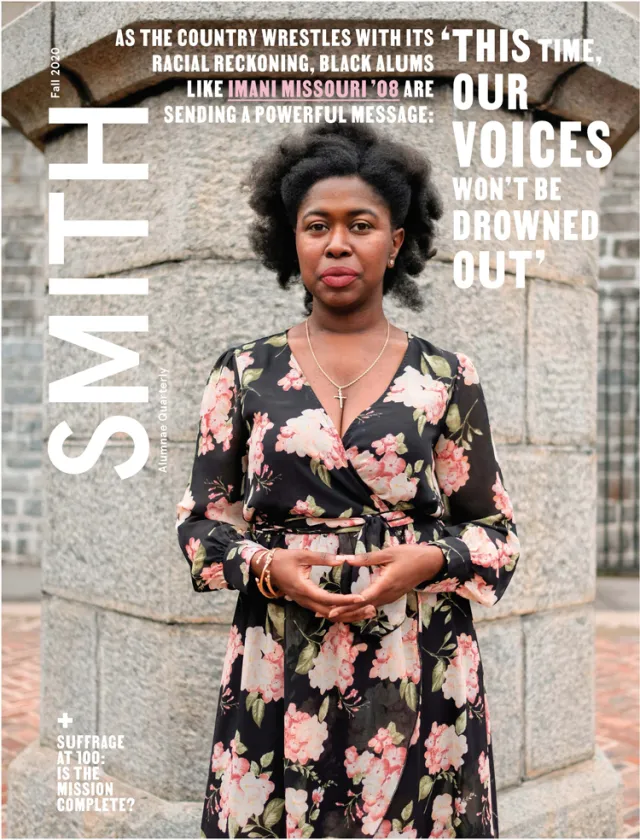

‘A Better Way Toward Freedom’

Cries for justice, equality and an end to systemic racism rang out in cities large and small this summer following the tragic deaths—many at the hands of police officers—of Black and brown people, including George Floyd, Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor and too many before them. The country’s racial reckoning was a long time coming; in the months since the marches began, activists, politicians, scholars and other leaders have asked, What’s next and how do we keep the momentum going? On the pages that follow, we hear from four alumnae who are, in various ways, on the front lines of the anti-racism movement about the difficult—but hopeful—road ahead.

Here, alums on the front lines of the anti-racism movement weigh in on the difficult—but hopeful—road ahead.

This Is Not a Drill: White women must use their privilege in support of Black liberation. By Imani Missouri ’08

We Must Demand More of Ourselves: The struggle for true freedom builds through the generations. It’s our turn now. By Ariana Quiñones ’16

Feeding a Revolution: Gaïana Joseph ’17 brings food to social justice demonstrators—and food security to underrepresented communities.

Photograph by Lynsey Weatherspoon