Portrait of a Poet

Alum News

Published June 13, 2017

Dorothy Moss ’95 was puzzled.

As a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Portrait Gallery, Moss was struggling over how to create an exhibition on Sylvia Plath ’55 that would make sense in that gallery. Her answer, she soon discovered, was right there within the poet’s journals and letters. Among the sketched self-portraits, paper dolls and photographs, Moss discovered a young Plath struggling to form her identity—and doing it not just in words, but visually. “I knew that Sylvia Plath had considered majoring in studio art at Smith, and that she had loved to paint and draw as a child. Seeing the sketches made me see how much Plath understood things visually,” Moss explains. “If you think about how she presented herself in photographs, too, she was completely in control of her visual image—be it surreal or glamorous or intellectual.”

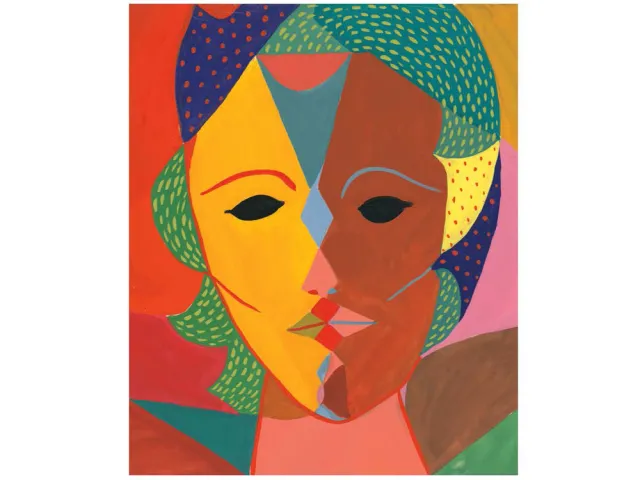

Sylvia Plath painted Triple-Face Portrait in 1950 or ’51, around the time she came to Smith. It’s one of several of Plath’s self-portraits in the National Portrait Gallery exhibition. Courtesy the Lilly Library, Indiana University. ©Estate of Sylvia Plath.

That impulse toward visual self-representation became the way in to a major new exhibition on Plath’s life and work, which opens June 30 at the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, D.C. Moss, in collaboration with Karen Kukil, Smith’s associate curator of special collections and a Plath scholar, would go on to create what Moss calls a “visual biography,” a collection of images, objects and manuscripts that tell the story of Plath’s life.

For Moss, creating the exhibition called on many strands of her experience—from her beginning as an undergraduate art history and English major at Smith to her promotion last winter to curator of painting and sculpture at the National Portrait Gallery.

One Friday in February, Moss and I sat down to talk in her Smithsonian office, a bright, cluttered room filled with pictures of her children and her husband and with mementos given to her by visiting artists and alumnae with whom she remains close. We discussed her life after Smith, her connection to Smith’s internship program at the Smithsonian Institution and her work in creating an exhibition devoted to the college’s most famous alumnae poet.

I first met Moss in 2007, when I interviewed her for a position as seminar professor for the college’s internship program at the Smithsonian (see sidebar, “Smithsonian Internship Opens World of Museum Work”). She had completed a master’s at Williams College but had not yet finished her doctorate in art history (University of Delaware ’12). Still, she was the clear choice for the job, a passionate scholar with a broad understanding of the field and a commitment to new ways of thinking about museums. For five years she taught a broad-ranging course in museum studies, introducing students to curators and practicing artists, auction house staff, journalists and even the secretary of the Smithsonian itself. Smith students loved her class. When, in 2011, the Smithsonian hired her as assistant curator in the National Portrait Gallery, Moss continued to work with Smith students as an intern supervisor and mentor, a role she has embraced every year since.

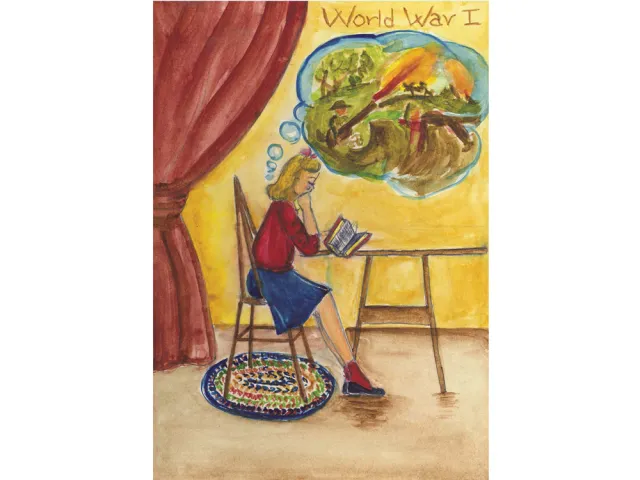

Sylvia Plath ’55 was a schoolgirl in 1946 when she drew this self-portrait, A War to End Wars.

Moss’ route into museum work was paved by Smith faculty and alumnae. In a methods class taught by Brigitte Buettner, the Louise Ines Doyle 1934 Professor of Art, Moss first read T.J. Clark’s The Painting of Modern Life, “which made me realize,” she says, “how being an art historian can lead to activism.” A class visit from Thelma Golden ’87, director and chief curator of the Studio Museum in Harlem, introduced her to the ways in which museums can give voice to marginalized people. Professor Barbara Kellum’s seminar on Pompeii “taught me how to talk about art with artists,” a lesson that has been crucial to her as a curator.

After college, Moss was guided into the museum field by Smith alumnae, as she interned first with Carolyn Kinder Carr ’61, deputy director and chief curator at the National Portrait Gallery, and then worked for Sarah Cash MacCullough ’80, then Bechhoefer Curator of American Art at the Corcoran Gallery (and now at the National Gallery of Art).

Since arriving at the portrait gallery, Moss has worked on exhibitions dealing with American workers (The Sweat of Their Face: Portraying American Workers), with soldiers (The Face of Battle: Americans at War, 9/11 to Now) and with the Chinese-American artist Hung Liu. She oversaw the commission of Karin Sander’s 2014 portrait of Maya Lin, designer of the Neilson Library renovation, and also directs the museum’s Outwin Boochever Portrait Competition. This year Moss conceived and curated the portrait gallery’s first performance art series, featuring commissioned performances by artists whose work is missing from the museum’s historical collections. Her goal as a curator, she says, is “to invite as many voices as possible into the conversation and to have every American see something of themselves in the museum.”

In 1954, Plath posed for this lighthearted “Marilyn” shot by photographer Gordon Lameyer.

Designing the Sylvia Plath exhibition has emerged as yet another way for Moss to connect deeply with her alma mater. Plath’s papers are housed in separate collections in the Mortimer Rare Book Room and Sophia Smith collections at Smith and at the Lilly Library at Indiana University. Moss pulled from both sources to illustrate Plath’s struggle to understand herself and the pressures faced by young women in the 1950s.

Some of the Smith College objects that will appear in the exhibition include Plath’s writing desk, made from a rough-cut elm coffin lid, which will hang high on one wall of the exhibit. Plath’s Girl Scout uniform, part of Smith’s Historic Clothing Collection, will also be included, as will the poet’s copy of The Autobiography of Alice B. Toklas, by Gertrude Stein, in which Plath has sketched her own hand sketching a scene in a Paris café. Framed drafts of poems, photographs and personal letters from Sylvia to her mother, all drawn from the Smith collection, will be displayed along with a light and sound installation by composer and artist Jenny Olivia Johnson.

One particularly poignant image shows a photograph of the poet under which she has written, “Look at that ugly dead mask here and do not forget it,” a glimpse into the complicated and sometimes cruel self-assessment reflected in much of Plath’s work. For Plath, Moss says, art was “self-fashioning,” an effort to exert control over how she was seen and how her voice was heard. Her notebooks were filled with portraits of real and imagined people, along with many self-portraits. “I found that to be quite remarkable and revealing about her visual imagination and her thought patterns,” Moss says. “In many ways I identified with this as I have always found drawing to be a clarifying process.”

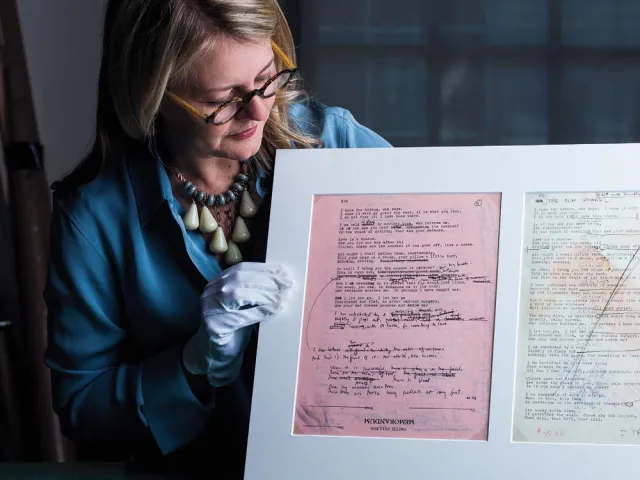

Dorothy Moss ’95 at the National Potrait Gallery with Sylvia Plath ’65 mannuscripts. Photograph by by Jimell Greene

Moss hopes that visitors to the exhibition will see parts of themselves in Plath’s efforts at self-creation. This is true especially of young audiences, she says, “whose own work of self-fashioning through social media seems to emerge from this same impulse as Plath’s.”

“Plath had a strong voice, a public voice that doesn’t shy away from difficult subjects,” Moss says. “It’s the kind of voice Smith teaches us to cultivate.”

Rosetta Marantz Cohen, professor of education and child study and American studies, has overseen Smith’s internship program at the Smithsonian Institution since 2008.

This story appears in the Summer 2017 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

SMITHSONIAN INTERNSHIP OPENS WORLD OF MUSEUM WORK

Smith’s internship program at the Smithsonian Institution began in 1979, when Donald Robinson, then professor of government and American studies, as well as a Smithsonian enthusiast, happened to sit next to Charles Blitzer, then assistant secretary of the Smithsonian, at a Smith trustee dinner at the college.

“We started sketching the program out on a napkin,” Robinson now recalls. “We sent our first class of interns that September.” Since that time, Smith has continued to send up to 10 students each fall term to work side by side with some of the nation’s preeminent scholars and curators. Students work four days a week as full- time interns while taking a museum studies seminar and engaging in an eight-credit independent project built around materials available through the Smithsonian museums and archives. The program offers undergraduate students an opportunity to do real museum work, whether helping to plan exhibits, writing wall text, researching information for books or websites or developing educational materials.

Over the years, the program has attracted American history majors and art historians, but also students in other disciplines—from science majors interested in the National Air and Space Museum to economics majors interested in nonprofit institutions and fundraising.

Jessica Nicoll ’83, director of the Smith College Museum of Art, was a Smithsonian intern. “The semester I spent at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden was a transformative experience,” Nicoll says, “paving the way for my career as a curator and, now, as a museum director.”

Recent Smithsonian Internship Alumnae and What They Are Doing

KATIE MIKULKA ’16

Assistant in the Smith College Mortimer Rare Book Room

CANDACE KANG ’15

Conservation technician for special collections at Harvard University

SHAMA RAHMAN ’13

Senior marketing coordinator at the Whitney Museum of American Art

SOPHIE ONG ’12

Doctoral student in art history at Rutgers University

KENDRA DANOWSKI ’12

Assistant director for civic engagement and social justice in the Eugene Lang College of Liberal Arts, New School for Social Research

Photograph by Jimell Greene