When We Went to War: Smith’s Hidden Weapon

Alum News

Published June 7, 2019

Early in 1942, just weeks after the attacks on Pearl Harbor, mysterious typed invitations began showing up in the personal mailboxes of select Smith seniors.

“If you are interested in enrolling for a course, which will prepare you for work of a confidential nature with the Government in the fall, please telephone the Vocational Office immediately. … Please do not mention this communication to anyone.”

The 65 seniors who received invitations may not have grasped the full meaning, but they surely knew it was an opportunity to join the war effort. Eligible male faculty and employees had begun enlisting as soon as war was declared. Now students had their chance. Smith President Herbert Davis had already declared Smith’s intention, “in common with all our colleges and universities, to take its full share of the national war effort.” At the same time, Edward C. Elliott, chief of the Division of Technical and Professional Personnel of the War Manpower Commission, took a more compelling stance: “All women college students are under obligation to participate in very necessary community service, in war production, or in service in the armed forces.”

Saying “Yes” to the Navy

The mysterious messages, as it turned out, were on behalf of the Navy, which was seeking Smith women who could be trained in cryptology—in other words, to become code breakers. One invitation landed in the mailbox of the late Anne Barus Seeley ’42. “I was very much a pacifist at first,” recalled Seeley when we spoke in 2018, some four months before she died at age 97. Seeley had come to Smith as a Quaker, she said, but eventually came to believe “We have to fight this war, so I said yes to the Navy.”

The mysterious messages, as it turned out, were on behalf of the Navy, which was seeking Smith women who could be trained in cryptology—in other words, to become code breakers. One invitation landed in the mailbox of the late Anne Barus Seeley ’42. “I was very much a pacifist at first,” recalled Seeley when we spoke in 2018, some four months before she died at age 97. Seeley had come to Smith as a Quaker, she said, but eventually came to believe “We have to fight this war, so I said yes to the Navy.”

Marjorie (Jerry) Rugge Scott ’42, a French major, was another student who accepted the invitation. In a letter in which she recalled her participation, she said, “It mainly consisted of cryptograms, from quite simple ones to ones that were more and more complex.”

Finding women to decode cryptograms was part of a Navy strategy to “release a man to fight at sea.” In peacetime, the Navy had used men’s colleges and universities to recruit and train male cryptanalysts, those who analyze and break codes used in communications (troop movement, ship courses, munitions, supply routes, etc). With men deploying to the field, women—despite early reservations the Navy expressed about their capabilities—were available and, as time would demonstrate, very capable.

Cryptanalysis was not a public occupation. Recruiting took a delicate touch. Rear Adm. Leigh Noyes, director of naval communications, raised the issue of confidentiality as a paramount concern. “It might be advisable to call the training by some other name, for instance, ‘Naval Communication Training,’ omitting the use of the word ‘cryptanalysis’ in any public manner.”

Thus began a three-year project to train Smith women in communications to work in Washington, D.C., for the Navy. Few knew of the true nature of the training. The general student body and the faculty did not know. Most administrators did not know. Even students who worked in Washington were unaware.

Retired Lt. Mary Jane English Schmitz ’44, Navy Reserve, graduated in the accelerated program in December 1943. During her years as a student at Smith, and while in the Navy, she said she never heard of a course in cryptography at Smith, nor was she aware of the invitation from the Vocational Office. In fact, when I contacted her in 2018, she thought it was a ruse, which I had to refute and assure her it was not. Even so, she chose not to disclose the details of her work in naval communication, keeping it under wraps for almost 75 years.

Retired Lt. Mary Jane English Schmitz ’44, Navy Reserve, graduated in the accelerated program in December 1943. During her years as a student at Smith, and while in the Navy, she said she never heard of a course in cryptography at Smith, nor was she aware of the invitation from the Vocational Office. In fact, when I contacted her in 2018, she thought it was a ruse, which I had to refute and assure her it was not. Even so, she chose not to disclose the details of her work in naval communication, keeping it under wraps for almost 75 years.

Those who “needed to know” about the Navy project included President Davis (and acting President Elizabeth Cutter Morrow 1896 prior), Dean Hallie Flanagan Davis, Vocational Secretary Marjory Nield and two key faculty—Myra L. Johnson, assistant professor of zoology, and Vivian Trombetta Walker, a botany instructor. Davis described them as “two young members of our science faculty who have adequate mathematical training who are very keen to undertake this work. They are both extremely gifted teachers, and living on the campus, they would have the advantage of knowing the students of the senior year who could be safely approached for this purpose.” Later, Walker left the college and was replaced by B. Elizabeth Horner, an instructor in the zoology department.

The Path to Becoming a “Code Girl”

The Vocational Office’s role in recruiting was key: It gave the project a logical home, as this training was in preparation for work post-graduation. Nield acted as the recruiter and Johnson and Walker hosted evening sessions for the students. They assigned each of the 12 course lessons in sequence, reviewed students’ work for completeness, sent the results back to their Navy contact and assured confidentiality. The goal was to get as many women trained and working in Washington as quickly as possible.

Of the seniors invited so mysteriously in early 1942, more than half called the Vocational Office for interviews, which consisted of two key questions: Do you like puzzles? Yes. Are you engaged to be married? No. The expectation was that these students would be interested in the detailed work of discerning patterns and would have the social freedom to relocate to Washington, D.C.

Once selected, the seniors formed groups of 10 to 12 and started meeting in classrooms in Smith’s science building for evening instruction. Initially this project was considered extracurricular, without credit and not appearing on any transcripts. Over time, the course was included in the War Minors curriculum, using the title Naval Communications. Keeping the study secret was paramount. Those who were successful and persistent were becoming “code girls.”

After graduation, “code girl” Jerry Scott went home to New Jersey and then to Washington, D.C., to work in the main Navy building on Constitution Avenue. “There I joined a large group of civil servants, male Navy officers and enlisted men working in a big room,” Scott recalls. “[There were] strings of numbers in front of each one of us. I was informed that we were working on the Japanese naval code and were trying to find the ‘additives’ that the Japanese cryptographers had added to the numbers that composed their coded messages.”

After graduation, “code girl” Jerry Scott went home to New Jersey and then to Washington, D.C., to work in the main Navy building on Constitution Avenue. “There I joined a large group of civil servants, male Navy officers and enlisted men working in a big room,” Scott recalls. “[There were] strings of numbers in front of each one of us. I was informed that we were working on the Japanese naval code and were trying to find the ‘additives’ that the Japanese cryptographers had added to the numbers that composed their coded messages.”

By the summer of ’42 there were 24 graduates of the Naval Communications course at Smith, and a fall 1942 registration of 43 more. The success of their work in Washington was acknowledged by Cmdr. John Redman in a letter from July 20, 1942, in which he asks for as many graduates as Smith College can send. “As more of the young women in last year’s Naval Communications report here for duty, we feel that we should not only repeat our expression of gratitude for your splendid work, but also that we should inform you frankly of our dependence on you for the continuation and expansion of this project,” Redman wrote.

“We Were Warned Never to Mention Our Work”

After working as a civilian code breaker in D.C., Jerry Scott joined the WAVES (Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Services) and the naval officers’ training program at Smith, and then returned to D.C. as a naval ensign. She and several other Smith and Mount Holyoke women rented a house and went to work in the Naval Communications Annex.

Read more about the WAVES naval officers’ training program at Smith at Learning to “Be Navy”

“We were all warned never to mention what we were working on to anyone ever, under punishment of death,” Scott wrote, adding that she had felt guilty even reading about the code breakers in the years following the war. “We never discussed what we did, even after the war, but I’m quite sure that some of my friends must have worked with the German code, enemy ship movements, weather in the Pacific, etc.”

Anne Seeley also recalled the secrecy, and the strings of numbers that carried hidden messages. “If we captured a Japanese ship, they [the Japanese] would change their code book and start over again. We always broke in,” she said. “It was tedious in the details and exciting in the theory.”

It is hard to imagine all the discussions that took place to decide to launch this project at Smith College in 1942. The last class appeared to finish in February 1945. Notes are sketchy and incomplete in the Smith College Archives, culled from the files of President Davis’ correspondence, the WWII Vocational Office, and those of the WAVES. A small number of code-breaking alumnae are still alive; some continue to remain silent about their involvement.

Those participating in the program consistently believed that women could do this work well, that the Navy offered a temporary opportunity at wages comparable to men’s and that doors to other careers might open because of this war service. However, after the war, many of the Smith code breakers returned to civilian life in roles as wives and mothers. It should never be forgotten that in the silence of their service, they took on a monumental task and did it well and discreetly.

In looking back on her own service, Jerry Scott remembers fondly the camaraderie of living and working alongside other women whose intellect had led them to a critical job.

“At times it seemed almost like a continuation of our dorm life at Smith,” Scott wrote. “We were all aware, though, that what we were doing was a very important job, hopefully leading to a more rapid end to the war.”

Summer 2019 Smith Alumnae Quarterly

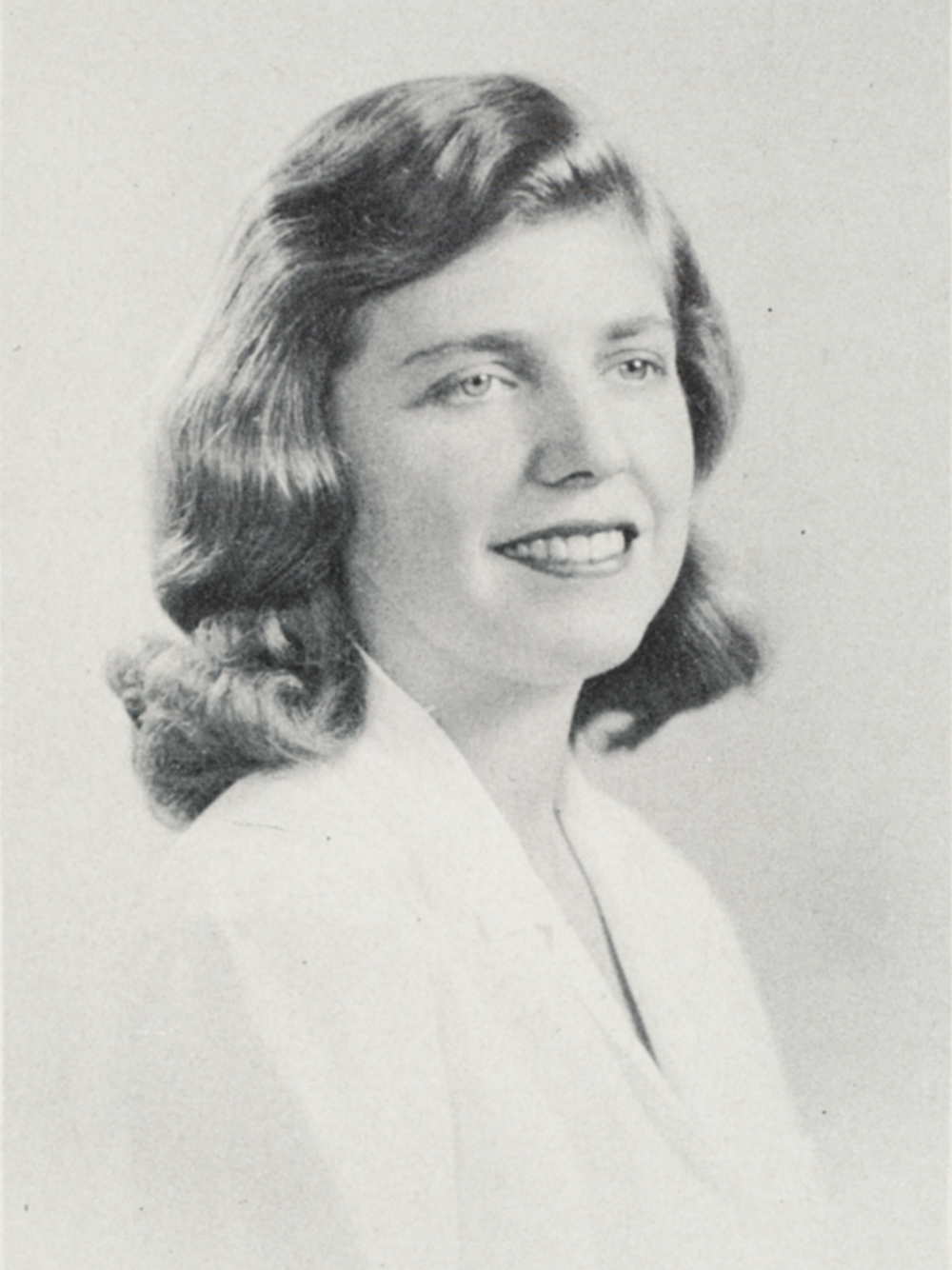

Headshots courtesy of Smith College Special Collections.

Karen Pell ’74, Ph.D., is a retired applied social scientist who spent the last seven years of her career at the National Security Agency. She lives in Columbia, Maryland.

Illustration by Barbara Ott