How Can Communities Adapt to a Changing World?

Alum News

Published March 27, 2020

Ten years ago I moved home to help care for my father. This meant basing my global climate and sustainability advisory work in the mountains of central Idaho. My father’s health was in trouble, and I could work from anywhere, so it was an easy decision. In December 2009 I left my temporary home in Copenhagen, where I had been laboring toward a new global climate agreement at the United Nations talks. The personal reward of moving home to Sun Valley was clear; what I could not know then was how much that change would dramatically shift my work and my perspective on how to build the future we want.

The World Economic Forum’s 2019 Global Risk Report, Out of Control, found the top two risks facing our planet are extreme weather events and the failure of climate change mitigation and adaptation. The U.S. government’s Fourth National Climate Assessment by 13 federal agencies underscored this last year, stating, “Climate change creates new risks and exacerbates existing vulnerabilities in communities across the United States, presenting growing challenges to human health and safety, quality of life, and the rate of economic growth.”

In Sun Valley, we are seeing this firsthand in our very special part of the West.

Three years after I moved home, the second megafire in seven years hit our community. The Beaver Creek Fire ravaged 100,000 acres over two weeks in August in the heart of our summer tourist season. It was the largest fire in the nation that season—until a devastating Yosemite fire just a week later. Billowing dark smoke ballooned up from behind Sun Valley’s iconic Bald Mountain as symphonygoers raced to respond to mandatory evacuations and air tankers dumped fire retardant and water across our burning forests and sagebrush hillsides. The county’s economy immediately lost $40 million, with lingering impacts: August is now known as “smoke month,” with summer events increasingly crunched into July, packing hotels and shrinking our summer season into a smaller and smaller window that people hope will be smoke free. The tourism economy is fueled by hospitality jobs that are part time, low-paying, seasonal and highly vulnerable to the whims of visitors and the unpredictable world of climate change. When tourists go away, the jobs do, too.

When we bring a resilience lens to community development, we are readying communities for our rapidly changing world.

Climate change is acting as a “threat multiplier,” exacerbating existing challenges of geographic isolation, a high-desert climate and unsustainable resource use, extreme income disparity and a highly concentrated tourism-based economy that relies on snowy recreation in the winter and clear blue skies in the summer.

Megafires are fueled by trees made vulnerable by drought and by pine bark beetles that live longer than they used to. Warming rivers are decimating fisheries and drought is affecting agriculture. We are located at the edge of a grid powered by still too many fossil fuels. Despite nearly 200,000 acres of agricultural land, we import 97 percent of our food, putting our food prices in the top 10 of U.S. counties. We are consuming Idaho’s precious water resources faster than they are naturally replenished.

What this area needed, I realized, was a plan, a concerted effort to grow its resilience in the face of climate change. Five years after arriving home, I joined with others to develop the Sun Valley Institute, A Center for Resilience, to help our community build enduring quality of place, by turning our risks into opportunities and advancing solutions for economic, ecological and social resilience. People love to visit Sun Valley, so we felt we had the chance to be an innovation laboratory; given our demographics, economy and state policies, solutions that work here can work anywhere.

We have been testing strategies since 2015. Our first steps were to address obvious near-term major risks, including fire, energy and water vulnerability and a lack of food and agricultural resilience. We tapped the expertise of the University of Idaho and our county to address fire risk. We accessed private capital markets by conducting the first solarize campaign in Idaho, which resulted in putting in five times the number of solar installations in 20 weeks as in the entire previous year, mobilizing nearly $1 million in investments, creating jobs, saving money on power bills, reducing our carbon footprint and developing local energy that is more resilient than the grid. We have partnered with the Idaho National Laboratory to plan critical infrastructure backup projects for fire, police and medical facilities. To address our food issues, we are increasing demand for local food with strategies like a $5 for Farmers weekly purchasing pledge and by connecting farmers to restaurants and stores. We are advancing regenerative agricultural practices, which increase productivity and sequester more carbon while increasing drought tolerance. We’re also helping to capitalize food infrastructure such as storage and processing.

When we bring a resilience lens to community development, we are readying our communities for our rapidly changing world. We are finding solutions that deliver on multiple fronts: benefiting our environment, creating quality jobs that help to reduce income disparity and diversify the economy, reducing energy and food costs, building community and increasing our safety and security. Rural communities desperately need new opportunities, and by building from the ground up, we can find solutions that match local values, that are lasting and scalable, that build enduring quality of place.

This story appears in the Spring 2020 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

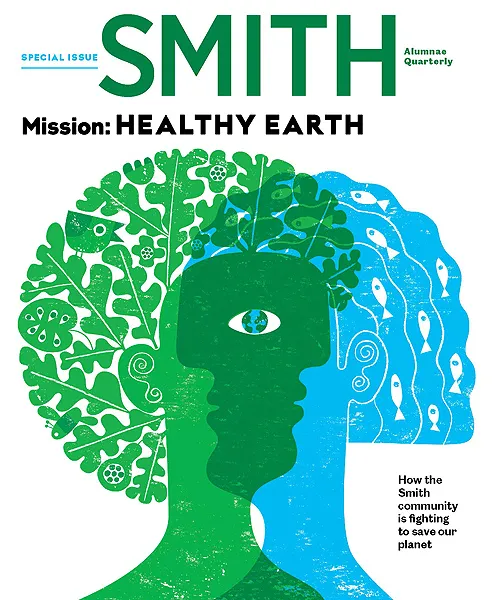

SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY

Special Climate Issue

Mission: HEALTHY EARTH

How the Smith community is fighting to save our planet

SMITH ID

AIMÉE CHRISTENSEN ’91

Sun Valley, Idaho

FOUNDER and executive director, Sun Valley Institute; founder and CEO, Christensen Global Strategies

MAJOR: Latin American studies, anthropology

FURTHER EDUCATION: J.D., Stanford Law School

When environmental strategist Aimée Christensen ’91 moved back to her Idaho hometown, she set to work creating a climate resiliency plan. Photograph by Kevin Syms