The Economic Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Women

Research & Inquiry

Published June 30, 2021

“My child care center closed during the stay-at-home order here in California, which means that my husband and I are desperately trying to balance working from home with caring for a 3-year-old,” said Stephanie, a parent quoted in a report to Congress last year titled Child Care in Crisis compiled by 11 advocacy groups. Stephanie took partial unpaid leave to care for her son, but then his school closed permanently and the only child care they could find was more expensive.

When the pandemic hit, stories like Stephanie’s unfolded across the country as women struggled to continue working while child care centers closed and schools went remote. Parents nearly doubled the time they spent on kids’ education and household tasks, with mothers spending significantly more time on average than fathers—15 hours more per week, according to a study by the Boston Consulting Group—and women’s employment began to suffer. Other studies like “COVID-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours” in Feminist Frontiers showed that in families with young children, the reduction in work hours for mothers was four to five times the reduction in work hours for fathers during the first few months of the shutdown. Consequently, the gender gap in work hours increased by 20–50%. Women’s stress levels increased and their livelihoods languished, which disproportionately affected low-income women and women of color in particular.

Stephanie was lucky—she still had a job. But a report by the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics in April 2020 found that the unemployment rate for women had gone up to 16.2%—almost three percentage points greater than the rate for men. And calculations by McKinsey & Company, a management consulting firm, showed that while women made up 46% of the U.S. workforce before the pandemic, they suffered 54% of the overall COVID-related job losses. According to the National Women’s Law Center, by February 2021 the U.S. women’s labor force participation rate was the lowest it had been since 1988, and more than 2.3 million women had left the workforce entirely. A report by The Century Foundation and the Center for American Progress (CAP) estimated that the cost of mothers leaving the labor force and reducing work hours amounted to $64.5 billion per year in lost wages and economic activity.

Unlike many women, Stephanie could telework and take unpaid leave. However, according to the International Monetary Fund, 54% of women in the United States work in sectors where telework is not available. And many women can’t afford to take unpaid leave to care for children. The Pew Research Center found that in 40% of U.S. households with children, women are the sole or primary breadwinner, and 9 million women are single moms. Sarah Jane Glynn, a senior fellow with CAP, told me that women who scaled back or dropped out of the workforce to care for family members could suffer consequences for years to come. “I have real concerns that we are going to see a lot of difficulty for some of these mothers reentering the workforce if there is this notion in the back of a hiring manager’s mind, thinking, ‘Well, she left the workforce to take care of her kids before. We’ve got this man over here who kept working consistently.’ Who are they going to offer that position to?” Glynn’s concern is supported by CAP’s data from prior recessions, indicating that when people are unemployed for 26 weeks or more, they have a harder time finding employment, and the longer they are out of work, the harder it is.

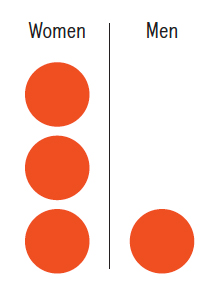

Women ages 25 to 44 were almost three times as likely as men to not be working because of child care demands during the pandemic.

Women leaving the workforce will not only impact their ability to find future employment, it will also impact their wages. A National Bureau of Economic Research report predicted that COVID-19 will likely widen the gender wage gap by five percentage points—so the average female worker would earn 76 cents for every dollar the average male worker makes, with the gap greater for women of color. “Hard-won progress on closing the gender wage gap may be set back decades,” concluded a CAP report. Glynn fears that the pandemic could continue to affect women over the next 40 years—as they hit retirement age, they’ll have lower Social Security and retirement benefits from earning less income.

The pandemic is also exposing a connection between women’s employment and access to child care. A survey of 2,557 working parents conducted by Northeastern University from May to June 2020 found that 13% of U.S. parents had to quit a job or reduce their work hours due to a lack of child care. And according to an April 2020 analysis by the Becker Friedman Institute, 11% of the workforce had child care duties that kept them from returning to full-time work until schools and day cares fully reopen. Since women ages 25 to 44 were almost three times as likely as men to not be working because of child care demands during the pandemic—according to research from the U.S. Census Bureau and Federal Reserve—women’s employment has been more severely impacted by a lack of child care than men’s.

COVID-19 will likely widen the gender gap, writes Professor Carrie Baker.

Though many parents can’t afford not to work, they also can’t find affordable child care. Data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics shows that over the past two decades, the cost of child care has more than doubled. And, according to the advocacy group Child Care Aware of America (CCAoA), the average cost of child care in the United States is over $9,000 a year. CCAoA also found that in 30 states and Washington, D.C., the average annual price of center-based child care for an infant was higher than in-state tuition and fees at a public four-year college; nationally, center-based child care for infants cost single-parent families 36% of their household income on average.

CAP research indicates that even before the pandemic, half of American families lived in “child care deserts”—areas where there are not enough day care centers—and among those families, mothers were much less likely to be employed. According to Procare Solutions, a child care management software company, by the end of 2020 more than one in four child care providers nation-wide had closed. And a survey by the National Association for the Education of Young Children last November found that 56% of providers who stayed open lost money due to lower enrollment combined with increased costs for cleaning supplies, personal protective equipment and additional staff wages.

The pandemic has pushed the child care sector to the brink of collapse, but Congress is finally trying to address this challenge. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 invested $39 billion in direct relief funding to the child care sector. Combined with prior COVID relief legislation, Congress has allocated more than $50 billion in relief funding. The American Rescue Plan also provided a child tax credit for families, lower Affordable Care Act premiums and extended postpartum Medicaid coverage.

The Biden-Harris administration’s two proposals—the American Jobs Plan and the American Families Plan—extend support for children by allocating $25 billion for upgrades and construction of child care facilities, extending child tax credits and providing universal preschool. “If there is one positive that has come out of the pandemic,” says Glynn, “it is a recognition of the importance of caregiving, and that we really need to be thinking critically about caregiving supports as important economic supports.”

Carrie Baker is a professor of the study of women and gender at Smith.

This story appears in the Summer 2021 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Read More Smart Ideas for a Post-Pandemic World

Educational Inequality: Janelle Bradshaw ’00, ‘Make Equity Your Guiding Principle From Day One’

Parenting: Rachel Sturges ’02, ‘I Cherished the Intimacy That Developed From Us Being Together so Often’

Education Policy: Lisa Daniels ’12, ‘We Need More Civic-Minded People to Step Up’

The pandemic has pushed the child care sector to the brink of collapse, but Congress is finally trying to address this challenge. Illustration by Franziska Barczyk