A Place to Celebrate Art: SCMA at 100

Smith Arts

Published December 3, 2020

Back in the fall of 2019 at a gala in New York City to kick off a yearlong celebration of the Smith College Museum of Art’s centennial, President Kathleen McCartney spoke about the museum as the “jewel” of Smith’s campus, a place where, as she said, “anyone from the community could come together in celebration of art.” To help mark the milestone, she encouraged everyone at the event to make time to come back to campus, walk through the galleries and experience the collection in the most powerful way possible—in person.

Nobody could have predicted that in just a few months, the idea of visiting the Museum of Art would be relegated to the imagination as the coronavirus pandemic forced Smith to move to a remote semester and the museum to close to the public for the first time since its top-to-bottom renovation in 2000.

The closure upended the museum staff’s plans for a series of events and exhibitions in recognition of the 100th anniversary. But Jessica Nicoll ’83, director and Louise Ines Doyle ’34 Chief Curator of the museum, knew the museum’s value to the community and to the academic life of the college and encouraged her staff and curators to use this moment to think differently and innovatively about how to continue the centennial celebration and bring art to the community.

The Three Crosses, Christ Crucified Between the Two Thieves, ca. 1660 (fourth state of five) Rembrandt

In a wide-ranging interview conducted in the fall, Nicoll reflected on the role of art in these unprecedented times, the museum’s enduring mission, plans to diversify the collection and what’s in store for the museum’s next chapter.

Pivoting during the pandemic

What was it like to have to suddenly close, after you and your staff worked so hard to plan a yearlong celebration of the museum, its history and future?

When we had to shut down, we were already about eight weeks into our celebration, which had begun with Black Refractions, an exhibition of masterworks from The Studio Museum in Harlem. That exhibition was resonating so powerfully with the community, and we were just heartbroken and devastated that it had to be closed to the public. It has been a challenge because we all want a museum that is publicly accessible. Shutting down was a complete contradiction to the ethos of how we see our work.

How has the museum staff risen to the challenge of making the most of these difficult times and continuing to bring art to the community?

Despite being thrown this huge curveball, I think we were well positioned to adapt to the moment. In terms of the centennial, we’ve always viewed it as more about launching our second century and really thinking about what the museum needs to be in this moment. One of the first things was to prioritize communicating online and through our social media channels. Our goal was to essentially begin operating a digital museum. Thankfully, we’ve been able to move forward with a lot of the content that we had been preparing for the anniversary year; it’s just being presented in a different way. One good example is an exhibition called SCMA 100 Then/Now/Next, which looks at the past, present and future of the museum through the lens of the collection. We’re looking forward to sharing the exhibition with visitors once the museum is able to reopen, but until then we’ve adapted it as an online exhibition through our website as a way to introduce people to the ideas we’ve been thinking about.

This conversation about new ways of offering art during the pandemic reminds me of a topic you raised once before—the idea of making a museum. How do you make a museum that functions in a way that is right for the moment and does what you want it to do, which is draw people in to experience the art?

One of the first things is to help people recognize that museums are not fixed things. A museum has core responsibilities, often around collections, but it is an evolving idea. It’s an idea that has its roots in the Enlightenment and has been pushed and shaped throughout its history. Early on, it was about preserving things. We’ve arrived now at a moment where thinking about museums has shifted to understanding that preservation is done for the good of humanity. After all, museums exist to support the communities they serve and should evolve as those communities change. The Smith museum maps the history of Smith; it has evolved in a way that has been responsive to the college’s needs of the time.

Art and equity

That idea of art being representative of the times leads me to ask how the Smith museum intends to respond to the country’s reckoning on race and racism. How will movements like Black Lives Matter reshape SCMA?

This summer was a moment of reckoning for museums at large and on our campus as well. It is a fact that museums are a byproduct of a colonial enterprise, and they have that history in their genes. For the museum staff, this moment is a call to action to interrogate all of our processes and all of our assumptions. We are actively working to make sure that when we reopen, we are operating in a different way and that we’ve advanced our own learning around issues of race and racism. We are looking at what we’re showing and what we’re saying about it and making sure that we all understand the complex histories that connect to holdings in our collections.

One Who Watches, 1995, Emma Amos

As Floyd Cheung [vice president for equity and inclusion] has said, this work is critical, but it’s never going to be done. Is the museum ready for the hard work?

I believe we are. As with all learning, you learn more and realize there is more to learn. We know there is work to be done in thinking about the culture of the museum and in diversifying our hiring. As a staff, we are having conversations about maintaining the urgency of this moment and how it can inform our work moving forward. We are committed to an anti-racism curriculum. This spring we organized a diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion working group, and we’re working with the Office of Equity and Inclusion to help us identify where we’ve made progress and what we should be focusing on. Our curators have also written a new collecting plan that centers diversity, equity, accessibility and inclusion in its goals. It very explicitly acknowledges that museums have a lot of power in choosing what stories get told and whose work gets seen, and that we need to exercise that power thoughtfully and work to make decisions that build a more inclusive collection, not only in our contemporary holdings but across the historical span.

Faculty regularly rely on the museum and its collection for their classes. How is the museum being used now, as faculty teach remotely?

We’re working with well over 20 classes across 12 academic departments. Of course, people can’t come to the museum, so we’re teaching classes from the museum’s galleries using Zoom and other technologies, and we’re sharing digital reproductions of artworks, so faculty and students are still engaging with art. We’ve also hosted events, like a series we called Tea with the Curators, where our curators explored the five senses through artworks in our collection. The museum is a huge partner to the faculty, and it’s been fun figuring out new ways of keeping the academic experience going even while we’re closed.

Critical to the college’s mission

What impresses you most about the museum’s history?

Our origin story is unlike any other college museum’s. Usually, there was a benefactor with a collection that went to the college and served as the foundation of a museum. At Smith, though, the earliest collecting was done by the college’s president and remained that way for probably the first 40 years or so. That speaks to how critical art has been to the college’s academic mission since its earliest days. One other thing that is particularly significant is what I would call moments of intervention by students to signal a direction they wanted the museum to take in its development of the collection. The first example would be in 1911, when the museum’s first print—an etching by Rembrandt—was acquired by a student group called The Studio Club. Thanks to those students, we are now known for having an exceptional print collection. Then fast-forward to the late 1990s, when the Black Students’ Alliance worked with the museum to acquire One Who Watches, 1995, a painting by Emma Amos, who actually just sadly died this year. That was a turning point in opening the curatorial staff’s mind to the importance of representation in how the collection was being developed. In 2008, the Korean American Students of Smith (KASS), wanting to see their culture reflected in the museum and its priorities, also worked with us and raised the money to acquire Yong Soon Min’s large-scale installation Movement. Those moments of interaction with students have been transformative.

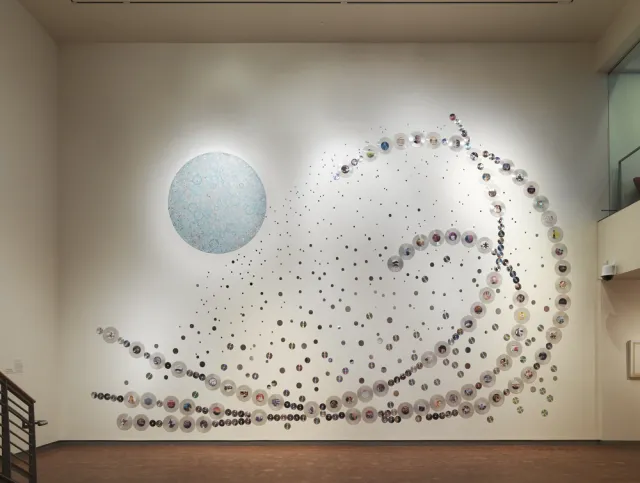

Movement, 2008, Yong Soon Min

You’re celebrating the museum’s history but also its future. What is your vision for the next decade?

My first priority is to ensure that any students who come to Smith absolutely see themselves in our museum. I want to make sure that we are creating a welcoming environment that feels genuinely like a reflection of our community and a place where people have a voice. We’re part of an academic enterprise, so there is opportunity for the creation of new works. I’d like to think that as an academic museum we can be a little more experimental and take some risks. I want to grow our artist-in-residence program. This year we welcomed [visual artist] Amanda Williams as the inaugural SCMA artist in residence, and it was an amazing experience. One other thing that I’d like to work on is eliminating our admission fee, which was instituted before I came. As I think about questions of accessibility, that feels like a barrier to full participation. I’d love to raise money to allow us to erase that charge and have the museum be free for everybody.

What role have alums played in building up the collection?

They have been hugely influential. Alumnae have been real visionary champions of the museum, often helping us to expand in areas where we fell short. An example would be the development of our Asian art collection. These days, about 90 percent of the artwork in the museum comes into the collection through a gift, with the majority coming from alumnae. We are currently, for example, bringing in a bequest of master line drawings from the collection of the late Carol Selle ’54 that includes drawings by Edgar Degas, Henri Matisse and Otto Dix, among others. We are already well known for our line drawing collection, but her transformative gift is going to add weight and consequence to it.

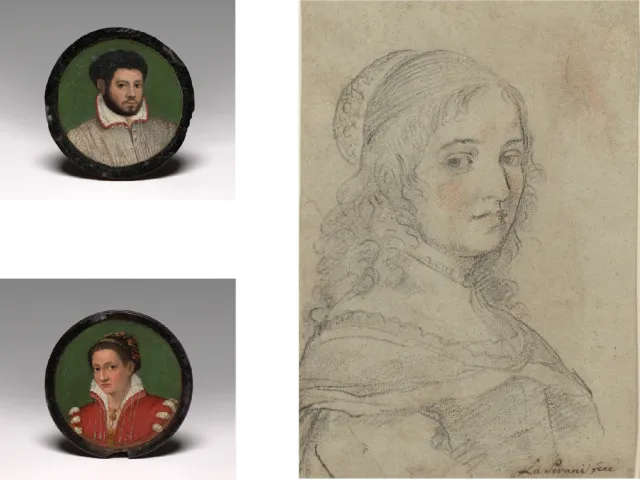

Portrait of a Man; Portrait of a Woman, ca. 1585–99 (marriage portraits), Lavinia Fontana and Self-portrait, ca. 1658, Elisabetta Sirani

How has the museum honored its commitment to advancing the perspectives of women artists?

Many people assume that the museum prioritizes collecting women’s art or is exclusively about that. While that has not been the historical origins of the collection, there has been careful thought given to the equitable development of the collection over the years, to understand that women are half of humanity and they should be at least half of the holdings in our collection. One of the exciting things that’s happening now is that we’ve been looking for opportunities to acquire art by historical women artists. That’s a heavier lift, but one of our newest curators, Danielle Carrabino, has made some very exciting acquisitions, including a pair of Renaissance marriage portraits by Lavinia Fontana. And we’ve purchased a 17th-century drawing—a self-portrait—by an Italian artist named Elisabetta Sirani. We are trying to make sure we represent women artists as much as possible across the scope of the collection.

What has the pandemic taught you about making art accessible to people, especially during difficult times?

If anything, this year has taught me that people are craving exposure to art, to ideas. They want to have rich conversations about artworks and just feel that they are looking at something beautiful and thinking about interesting ideas and that it’s not all trauma and uncertainty. Art brings us a lot of solace.

This story appears in the Winter 2020-21 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

SCMA at 100

The Smith College Museum of Art houses more than 27,000 objects representing a diversity of art, cultures and time periods. Enjoy the following stories in celebration of the museum’s centennial.

- Janice Carlson Oresman ’55, Connoisseurship for Life

- Thelma Golden ’87, ‘Central to My College Universe’

- Alums reflect on how the Smith College Museum of Art changed the trajectory of their lives

- ‘Oh, Good, There’s a Museum Shop!’

- A Rich Resource for Teaching: Museum collection inspires faculty across the curriculum

Museums are not “fixed things,” says SCMA director Jessica Nicoll ’83. They evolve to meet the needs of the communities they serve. Photograph by Mark Ostow