The Super Bowl of Astronomy

Faculty

How Smith professors prep for the upcoming solar eclipse

Photo by Liliana Hetherman ‘25

Published April 4, 2024

Meg Thacher is flying to Texas. James Lowenthal is leading a bus trip of about a hundred Smith students to northern Vermont.

When it comes to an event as big as a total solar eclipse, the Smith College astronomy department doesn’t mess around.

“People always ask me, What are the Smith professors doing for the eclipse?” says Thacher, whose phone has been ringing off the hook this week in anticipation of the historic and rare moment. “We’re all leaving town and going to watch totality. ... Because totality is just so amazing.”

Thacher, a senior laboratory instructor in astronomy and the academic director of the Summer Science and Engineering Program, has experienced a full eclipse just once before. In 2017, she and her family flew to Oregon, where in a tiny local state park they waited with a hundred other visitors. When the moon covered the sun, Thacher describes the moment as “heart-stopping.”

“I’d seen pictures of it, but it’s nothing compared to the actual live experience,” she says. “It stretches out bigger than you think. The sky is darker than you think. It got cold. The wind picked up a little bit. And you’ve got all these people around you and they go, ‘Yay!’ and then it‘s kind of a dead silence for a little while as people look at this thing. When the sun comes back, the people all cheer again.”

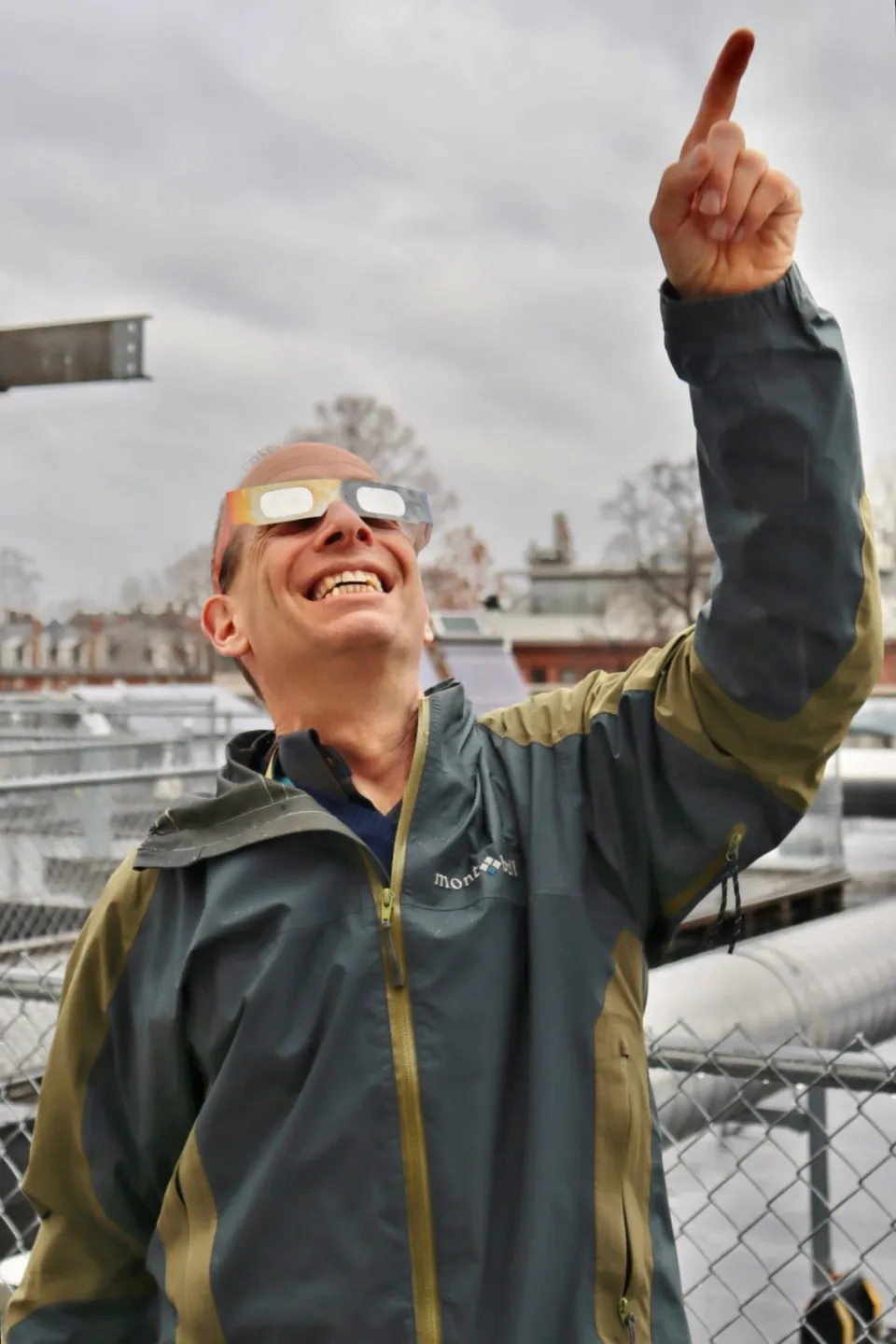

Meg Thacher in her “solar eclipse outfit.” She estimates she’s given eight public talks on the subject in the past two weeks. “Everybody in the United States is going to be looking at this eclipse at the same time and you can be a part of that.” Photo by Liliana Hetherman ’25

When it comes to how to plan ahead for viewing an eclipse, Thacher and Lowenthal—the Mary Elizabeth Moses Professor of Astronomy—recommend picking a location with good views and accessible bathrooms. Keep an eye on traffic at your chosen site and watch the weather closely, so that you can have an alternative plan if clouds move in.

For those remaining on Smith campus, the astronomy department is sponsoring an eclipse watch party at 2 p.m. on Chapin lawn with a giveaway of 1,000 free eclipse glasses. Lowenthal recommends that viewers pay attention to how the light changes and gets “thin” (in a way he compares to a summer thunderstorm) as the moon begins to cover the sun. Birds may stop singing, thinking that night is near, while nocturnal animals may briefly awaken.

“One really cool thing is that you’ll see crescents everywhere—on the ground, on buildings,” he says, adding that these images of the partial sun will appear “by the hundreds of thousands.”

A partial phase has its merits, adds Lowenthal, but there’s a reason most astronomy professors and many students will be heading to spots as close as possible to the centerline of the eclipse path.

Outside of that 100-mile zone of totality, he notes, “you never see the corona. You never sense the sky doing this incredible transformation from day to night right before your eyes. You don’t sense the shadow of the moon rushing over you at 2,000 miles per hour and this cosmic, epic, monstrous event.”

“In astronomy, you don’t often get to see things happen,” notes Lowenthal. “Here we’re watching the moon orbit and you see it right in front of your eyes.” Photo by Liliana Hetherman ’25

Ellie Walker ’26, a biological sciences major and an astronomy department teaching assistant, is joining the Smith group headed off campus, which is led by Lowenthal and sponsored by a grant from the Center for the Environment, Ecological Design, and Sustainability. “It isn’t often that I have the chance to witness how real and beautiful the phenomena of our solar system is,” Walker notes in an email. “I’m excited to experience totality with my friends and the overall Smith astronomical community—I am sure it is a memory that we won’t soon forget.”

This will be the fifth time Lowenthal has experienced a total eclipse. He says that each time, there has been an outburst of strong emotion among the viewers, as the sun—something that is normally dependable and predictable—abruptly disappears.

“It’s a surprise to many people how emotional it is and how strange and unusual and affecting it is. A lot of people shout or scream. Some people cry,” he says. “It is the definition of awe inspiring to experience. ... It’s an instant reminder of our own fragility and the smallness of the Earth in the cosmic scale.”

Such events are particularly notable for the way in which “the solar system mechanisms are laid bare”—an opportunity that’s rare in a field of slow movements and long distances like astronomy.

”You get to see orbits happen,” says Lowethal. ”It’s one of the rare chances and most spectacular opportunities to see physics and astronomy and science in action.”

Thacher agrees that the experience is a uniquely communal one that’s hard to compare. “We sometimes call a total solar eclipse the Super Bowl of astronomy.”