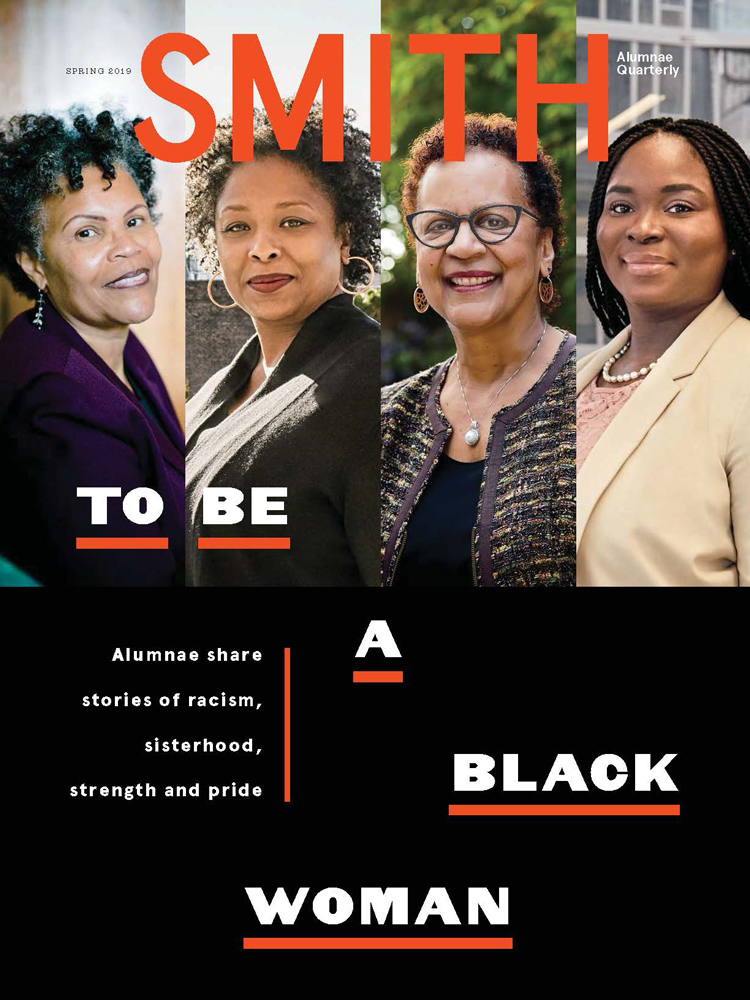

To Be a Black Woman—Why We’re Telling Our Stories

Alum News

Published March 15, 2019

BEFORE MY CLASS WAS ADMITTED IN 1970, African American women made up less than 1 percent of Smith College’s total student population. At that time, after years of racial turmoil across the country, America was finally beginning to open its eyes to the value of true integration and access to education.

Black students attending Smith during the late ’60s had collaborated with the college administration and admission office to implement ways to amplify black voices on Smith’s campus and to significantly increase the numbers of black faculty members as well as the black student population. Thanks to the determination of the sisters who preceded us on campus, 69 black women enrolled in the class of 1974; we represented more than 10 percent of the first-year class, making ours the largest class of black women in Smith’s history. What that meant for me—an 18-year-old from North Haven, Connecticut, with only three black people in my high school class—was that I would finally have a significant number of people who looked like me to enableme to experience that “sameness” and Black identity I so desperately sought in high school, while also finding and claiming my place as a black woman within the larger Smith community.

Many black women from the class of 1974 went on to significant achievements and rewarding careers. We graduated from Smith fully confident that we were ready and capable of becoming leaders in various capacities and fields. For many years, I served in managerial leadership and executive roles at AT&T and the Ford Foundation, and since my graduation I have remained closely connected to Smith, which contributed (alongside my experiences as a black woman, a daughter and mother and wife) to who I am today.

Many black women from the class of 1974 went on to significant achievements and rewarding careers. We graduated from Smith fully confident that we were ready and capable of becoming leaders in various capacities and fields. For many years, I served in managerial leadership and executive roles at AT&T and the Ford Foundation, and since my graduation I have remained closely connected to Smith, which contributed (alongside my experiences as a black woman, a daughter and mother and wife) to who I am today.

Over the decades—as I’ve been involved in various capacities with the alumnae association and the board of trustees—I’ve thought about what Smith is like for each new generation of students. I’ve remained concerned about how young black women are managing on campus and wonder what their lives are like outside the Grécourt Gates. Given their academic and social experiences at Smith, have they found the post-college world as welcoming as perhaps their white colleagues have? Were their post-college experiences, relative to “difference,” similar to mine?

These questions came rushing back last summer amid reports that a black student who was on a lunch break from her campus job had been questioned by campus police. She was questioned about resting on a couch in a house common area. One could not help wondering if a white student would have been asked the same question. The incident sparked a much-needed conversation about implicit and explicit bias, privilege and the unique experiences of black women. It also made me wonder about the world that Smith-educated black women are entering. Are they experiencing what Malcolm X once said: that “the most disrespected person in America is the black woman”?

The editors of the Quarterly were asking the same questions. They reached out to me and to another black alumna, essayist and novelist Martha Southgate ’82, to help them envision a package of stories that would attempt to highlight the successes and the challenges, the joy of sisterhood and the pain of prejudice experienced by different generations of black Smith women.

We brainstormed a list of alumnae to participate. Some wrote their own essays; others were interviewed by African American journalist April Simpson ’06, who captured their words and ideas in “as told to” essays. Their lives are varied and so are the thoughts they chose to share. We hope you find their words illuminating.

Deborah Archer ’93, “I’ve Picked a Lane. It’s Racial Justice.”

As a litigator and law professor, Deborah Archer ’93 uses her lived experiences to sharpen her focus on issues of equity, civil rights and the unique challenges facing black women.

Billy Dean Thomas ’14, “I Felt Like I Was Being Tokenized”

Is it inclusive if the only queer person of color at an event is the performer?

Caroline Clark ’85, “I Am Not Black or a Woman. I’m a Black Woman”

Why was I the one to be asked if I’m defined more by my race or by my gender?

Charlise Lyles ’81, “Who Came To Soothe My Soul? All My Black Sisters.”

At Smith, their smarts urged me on and helped me find my identity and my power.

Lori Tharps ’94, “I Yearned for a Comfort and Confidence in My Blackness”

Growing up immersed in white culture meant I had to go on a journey of discovery about my heritage.

“If We Listen To How Others Define Us, We Remain Stuck”

Sandra Williams ’75 is a senior vice president at CBS Television in Los Angeles, where she serves as deputy general counsel. In a conversation with journalist April Simpson ’06, she talks about the inner strength she developed as she navigated law school and her legal career.

Deanna Dixon ’88, “I’m Proud That Our Students Hold Us Accountable”

Unity. Community. These have made a silver lining as the campus has responded to acts of intolerance.

Joyce Young ’75, “Challenging the Status Quo by Writing My Truth”

When stereotypes challenge my sense of identity, my poetry brings me back to wholeness.

“What Excites You, Gives You Joy, Gives You Hope About Black Women in the World Right Now?

Sabine Jean ’11, “Am I the Only Black Person in Here?”

When you stand alone, every choice—to speak up, stand back or observe quietly—seems fraught

Vickie Shannon ’79, “Racism Is Their Problem—Not Yours”

A mother’s wise words leave a lasting message.

Stephanie Mickle ’94, “Black Women Can Rally Voters, Influence Elections and Win”

When black candidates run, diversity multiplies in political staffs and within parties.

Linda Smith Charles ’74 and Martha Southgate ’82