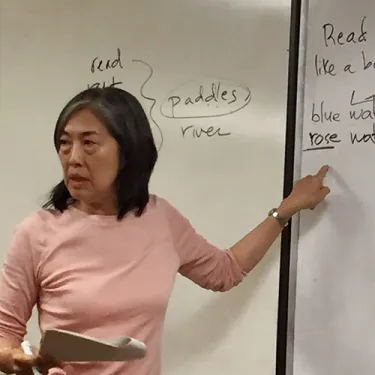

Cathy Song

Visiting Poet

A native of Wahiawa, Hawaii and of Chinese and Korean descent, Cathy Song‘s first volume of poetry, Picture Bride, won the 1982 Yale Series of Younger Poets Award and was nominated for the 1983 National Book Critics Circle Award. She has since written two other volumes of poetry, Frameless Windows, Squares of Light (1988), and School Figures (1994).

Her narrative poetry has been compared to “flowers: colorful, sensual and quiet… offered almost shyly as bouquets to those moments in life that seemed minor but in retrospect count the most” by Richard Hugo. Song’s focus on family, tradition, and community have been described by Asian American Literature as “the complete fusion of form, image, occasion, and emotion… a sudden eruption of metaphor, which startles, teases, illuminates.”

Though her volumes of poetry capture a unique immigrant experience that straddles Asia-Pacific and America, Song has consistently maintained that the rich world within her poems transcend her own ethnic and regional background, calling herself “a poet who happens to be Asian-American” and resisting classification as an “Asian-American” or “Hawaiian” writer.

Song currently teaches at the University of Hawaii at Manoa, and works as an editor for Bamboo Ridge Press. Her poems have appeared in an anthology of asian-pacific literature, and in Dark Horse, The Greenfield Review, and West Branch.

Select Poems

from a uiyo-e print by Utamaro

The light is the inside

sheen of an oyster shell,

sponged with the talc and vapor,

moisture from a bath.

A pair of slippers

are placed outside

the rice-paper doors.

she kneels at a low table

in the room,

her legs folded beneath her

as she sits on a buckwheat pillow.

Her hair is black

with hints of red,

the color of seaweed

spread over rocks.

Morning begins the ritual

wheel of the body,

the application of translucent skins.

She practices pleasure:

the pressure of three fingertips

applying powder.

Fingerprints of pollen

some other hand will trace.

The peach-dyed kimono

patterned with maple leaves

drifting across the silk,

falls from right to left

in a diagonal, revealing

the nape of her neck

and the curve of a shoulder

like the slope of a hill

set deep in snow in a country

of huge white solemn birds.

Her face appears in the mirror,

a reflection in a winter pond,

rising to meet itself.

She dips a corner of her sleeve

like a brush into water

to wipe the mirror;

she is about to paint herself.

The eyest narrow

in a moment of self-scrutiny.

The mouth parts

as if desiring to disturb

the placid plum face;

break the symmetry of silence.

But the berry-stained lips,

stenciled into the mask of beauty,

do not speak.

Two chrysanthemums

touch in the middle of the lake and drift apart.

From PICTURE BRIDE (Yale University Press, 1983)

She was a year younger

than I,

twenty-three when she left Korea.

Did she simply close

the door of her father’s house

and walk away. And

was it a long way

through the tailor shops of Pusan

to the wharf where the boat

waited to take her to an island

whose name she had

only recently learned,

on whose shore

a man waited,

turning her photograph

to the light when the lanterns

in the camp outside

Waialua Sugar Mill were lit

and the inside of his room

grew luminous

from the wings of moths

migrating out of the cane stalks?

What things did my grandmother

take with her? and when

she arrived to look

into the face of the stranger

who was her husband,

thirteen years older than she,

did she politely untie

the silk bow of her jacket,

her tent-shaped dress

filling with the dry wind

that blew from the surrounding fields

where the men were burning the cane?

From PICTURE BRIDE (Yale University Press, 1983)

His hair is brilliantined.

It is black and shiny

like patent leather.

Se cannot be more than twenty:

his cheeks are full,

his face is smooth as a baby’s,

though one pockmark

above his right temple

about the size of a rice kernel

is detectable.

His mouth appears to be

curved over something almond shaped.

Perhaps, he is sucking on a sweet plum.

His suit is puckered

at the seams.

The shoulders are too narrow,

fitting badly;

probably stitched

in a lamplit tailor shop

hovering in a back alley.

But the necktie adds

the texture of raw silk;

the added touch signifying

that this is meant to be

a serious picture;

the first important photograph

he has ever had taken.

This will document

his passage out

of the deteriorating village.

He will save it

to show his grandchildren.

As if already imagining them,

his eyes are luminous.

He is looking ahead,

beyond the photographer

in the dark room

crouched under the black velvet cloth,

beyond the noisy cluttered streets

pungent with garlic and smoke chestnuts.

Rinsing through his eyes

and dissolving all around him

is sunlight on water.

From PICTURE BRIDE (Yale University Press, 1983)