‘I’ve Picked A Lane. It’s Racial Justice.’

Alum News

Published March 12, 2019

From the minute she graduated from Yale Law School in 1996, Deborah Archer ’93 put her focus on one thing: fighting for racial justice via the law. Her passion comes not only from the rightness of justice as a moral issue but from personal experiences that helped light that fire in her heart.

She worked at the ACLU on state and federal racial justice litigation; later, as assistant counsel at the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, she litigated cases involving voting rights, employment discrimination and educational equity.

Her passion is not confined to her own work as an attorney. In the 15 years she taught at New York Law School, Archer guided students in crucial civil justice work, including enlisting their aid in drafting an amicus brief for the 2014 appeal in Fisher v. University of Texas, a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court ultimately upheld admissions policies that sought to promote diversity at the school. In July 2018, she joined New York University School of Law as an associate professor. She teaches the Civil Rights Clinic, in which students work on a wide range of civil rights and social justice matters through direct client representation, appellate advocacy and the development of advocacy campaigns.

Archer lives in Brooklyn with her husband, Richard Buery, who works at the KIPP (Knowledge Is Power Program) Foundation. Previously, as New York’s deputy mayor, Buery was instrumental in creating the city’s universal pre-kindergarten program. The couple has two sons, ages 15 and 12.

And if Archer weren’t a lawyer? Well, even in her fantasy alternate career, racial equity plays a large part. “I would probably be a photographer,” she says. “I often think about the love, hate, strength and beauty captured by those photographers who documented the civil rights movement through their photographs. And the impact those photographs had in advancing the calls for justice.”

What was your experience as a black woman at Smith?

Overall, I really loved my time at Smith. My parents are Jamaican immigrants, so I’m a first-generation American citizen and the first in my family to graduate from college and law school. I wouldn’t say that we were poor, but we struggled financially. So when I got to Smith, I was exposed to people and ways of living that I didn’t know existed. In that sense, Smith was wonderful and was really central in making me who I am today. But it also was central in shaping who I am in a way that was not so positive. In my first year in Tyler House, I received a racist note under my door. It called me the N-word and said I should go home.

Wow. That’s terrible! That’s so hard.

It was incredibly difficult. I had seen racial discrimination all of my life as a black immigrant growing up in Hartford, Connecticut. Very early on when we were living there, someone spray-painted “KKK” on the side of the house and on our car. So it wasn’t surprising to me that someone at Smith would do that. What was surprising was that I had felt so safe in that house. I had felt so welcomed. When that happened, it really shattered trust and my feeling of safety and belonging—not only in that house, but in the college.

Did you recover that feeling of safety before you graduated, or did it remain a mixed bag the rest of your time there?

I grew to feel more comfortable, but never fully comfortable and never fully trusting. You find your community, and I focused on that community there for supporting me. That’s what helped me leave with an overall positive feeling about Smith College and how the school helped position me to be successful in life.

What allowed you to carry both the anger and pain of the experience as well as the feeling that you could grow from it and not let it stop you?

I think the positive comes from the institutional response and the response of other individuals who were there. Smith took this very seriously and made me feel that they were going to do what they could do to address this and try to make me feel safe again. They brought in handwriting experts and took other measures to investigate this incident (though they were unable to find and prove who had done it). More than that, they made efforts to try to rebuild the community institutionally. The individuals who I interacted with—my friends and my head resident—really worked at making sure that I felt safe again.

What would you say to a student who faced an incident like this?

You have to figure out how you can empower yourself in difficult situations, and to make sure that people don’t get what they want. If I had crumbled and disengaged or if I had gone, that would have allowed them to succeed. My mantra in life is that I’m never going to allow someone else—their views, their biases—to deny me an opportunity. I find the support that I need, the network that I need, so that I’m going to get the same benefits that [those who are biased against me] are getting out of this experience.

I was lucky enough to see Michelle Obama during her recent book tour and as she spoke it was clear to me that she has had to mask some mannerisms, some ways of being that mark her as black. She grew up working class on the South Side of Chicago, so there’s slang she uses, for instance, that is particular to that upbringing. She spoke quite thoughtfully about how and why she downplayed that part of herself. I wonder if, in your career, you’ve had to mask in that way.

I absolutely feel like I’ve had to. Some of it is by choice, but some of it is by necessity; I think that’s part of the spectrum of oppression and discrimination. For example, I worked at a fairly conservative law firm. When I stopped perming my hair and had a natural—that was a big thing for me to do at a law firm. So even on a symbolic level, there’s a kind of masking. Part of moving from diversity to inclusion is not only having me here, but having me here in a way that allows me to embrace who I am. And for my lived experiences to influence the culture of this institution that I’ve joined. That said, more and more I’ve been able to become my true self when I’m at work. Some of that comes with institutional progress around equity and inclusion. Some of that has come from me, with age. I just feel like I am who I am and I’m not going to try to hide that anymore.

Do you feel that the challenges facing black women differ substantially from the challenges facing white women?

We need to take a step back and have that conversation about black women, because there are clearly different challenges that face black women and they get lost in the shuffle when we talk about challenges facing women and even sometimes when we talk about challenges facing black people, no matter what their gender. Just about every challenge that society faces, black women face it on a deeper level. I want to think through what those unique challenges are and find a way to address them. The broader conversation about gender equity and racial justice doesn’t necessarily get to the unique issues that are facing black women.

Absolutely. I also think that the challenges facing black women aren’t always across racial lines; for example, there are situations where there’s inequity between a black man and a black woman.

It’s very layered, and you can keep adding layers. Transgender women of color face unique issues. We look at, for example, the violence against women. Transgender women of color often face more violence than any other community. The intersectionality of life is still not fully explored and it’s particularly not explored when it comes to women of color.

Intersectionality is such a key word in talking with students. And so many young people feel very bleak about race relations in today’s polarized, angry climate. How do you talk to your students about the mood of the country?

It’s really tough. Some of the blatant racism that has come out from under cover was prompted by the election of a black president. That led to what we’re seeing today, and I think people are confused. To hold both of those things in our heads—that we can be making incredible progress toward equity on the one hand, but still have deep and profound challenges around racial equality on the other hand—is really hard. Too often people can’t see that there are both.

My students and other young folks I interact with do feel overwhelmed by injustice. They feel overwhelmed by the racism. I try to convey to them that it’s all about a cycle. When you look at where black people were in 1818, and when you look at where we were in 1918 and now you look at where we are in 2018, it does show you that progress is possible. And that people before us did not despair. Martin Luther King didn’t despair. Harriet Tubman didn’t despair. John Lewis, when he was fighting for voting rights, didn’t despair. Then who are we to despair when we are living and enjoying the fruits of their labor?

I also tell my students that everyone can choose a lane. The lane I’ve chosen is primarily about racial justice. That doesn’t mean that I don’t care deeply about other issues, but I know that other people are on it, and that I need to stay on this one. In this current challenging time, I think it’s just important for us all to pick a lane that we can fight in, and together we can move the needle.

Martha Southgate ’82 is the author of four novels, most recently The Taste of Salt. She is working toward an MFA in playwriting at Brooklyn College.

This story appears in the Spring 2019 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

SMITH ALUMNAE QUARTERLY

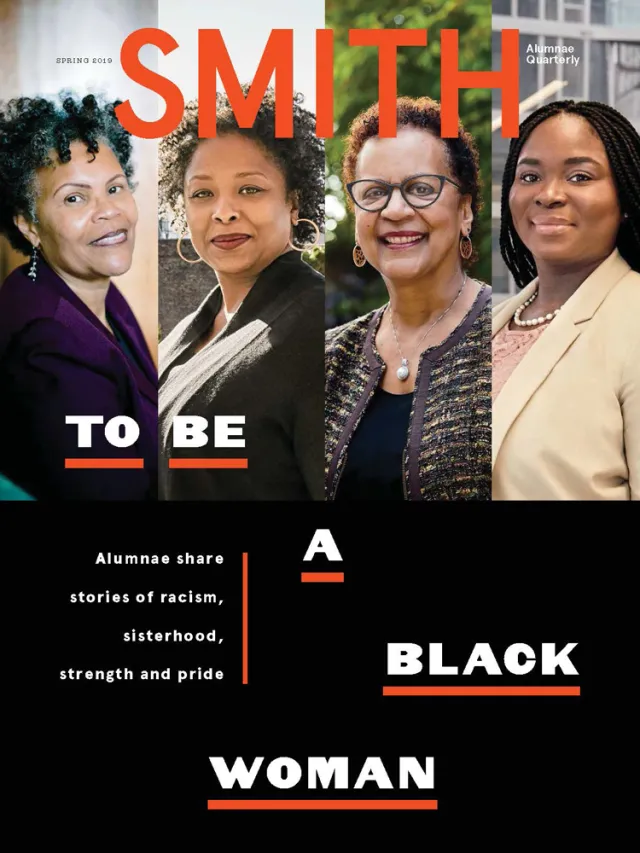

To Be a Black Woman: Alumnae Share Stories of Racism, Sisterhood, Strength and Pride

Billy Dean Thomas ’14, “I Felt Like I Was Being Tokenized”

Caroline Clark ’85, “I Am Not Black or a Woman. I’m a Black Woman”

Charlise Lyles ’81, “Who Came To Soothe My Soul? All My Black Sisters.”

Lori Tharps ’94, “I Yearned for a Comfort and Confidence in My Blackness”

April Simpson ’06, “If we listen to how others define us, we remain stuck” Q&A with Sandra Williams ’75, senior vice president at CBS Television

Deanna Dixon ’88, “I’m Proud That Our Students Hold Us Accountable”

Joyce Young ’75, “Challenging the Status Quo by Writing My Truth”

“What Excites You, Gives You Joy, Gives You Hope About Black Women in the World Right Now?

Sabine Jean ’11, “Am I the Only Black Person in Here?”

Vickie Shannon ’79, “Racism Is Their Problem—Not Yours”

Stephanie Mickle ’94, “Black Women Can Rally Voters, Influence Elections and Win”

Deborah Archer ’93 in her office at NYU law school. She brings a background in civil rights litigation to the classroom. Photograph by Beth Perkins.