‘Where I Became’: From South Africa to the Silver Screen

Alum News

The incredibly true story of a little-known slice of Smith history

Published June 11, 2023

One day in 2012, Tandiwe Njobe ’94 attended a strategy session at Standard Bank in South Africa, where she worked. During the lunch break, the global head of investment banking—the man leading the session—struck up a casual conversation with Njobe and at some point asked her where she went to college.

When she told him that she graduated from Smith, his response surprised her. “My wife went to Smith College too!” he said. “You two should meet.”

One email introduction later, Jane Dawson Shang ’82 and Tandiwe Njobe started a friendship that would lead to a life-changing experience for both of them. With little more than a healthy dose of curiosity and courage, they decided to make a feature-length documentary film, Where I Became, that would bring to light the incredible but mostly unknown story of Smith College’s South African scholarship program and the 16 women who were its beneficiaries.

But the road from that introductory email to an award-winning film was long and winding and makes for an excellent story in itself.

Shang and Njobe attended Smith more than 10 years apart. Njobe is a native South African who was raised in exile in Tanzania and Zambia, and Shang is an American with New England roots, but the two women immediately hit it off. After corresponding by email for a few months, they decided to meet in London, where Shang was living at the time. They ended up bonding over their Smith experience—both majored in economics—and their shared interest in travel and learning about people and culture. “Like Jane,” Njobe says, “I think I have a knack for just wanting to understand people, understand their journeys, understand where they came from, and understand why they do the things they do.”

As the two women learned more about each other and their similar experiences living and working abroad, an idea took hold to somehow share the remarkable story of Njobe’s family, particularly her parents. Her mother and father were career educators in South Africa who chose to live in exile as an act of defiance against that country’s horrific apartheid policies—policies that severely limited what Black South Africans were allowed to teach and learn. In exile, Njobe’s parents continued to teach and stressed the importance of education to their children. Njobe explained to Shang that her decision to go to Smith was the perfect epilogue to her parents’ story because she attended on a full scholarship specifically intended to give Black South African women the opportunity to get the college education that their own country denied them.

Because Njobe and Shang lived on separate continents and had other work and family obligations, the notion of telling Njobe’s family story remained in the idea phase. But when Njobe’s father died in 2014, they knew they couldn’t just keep dreaming about getting the story out into the world—they had to put a plan into place.

The question then became how to capture Njobe’s family story and how to tell it. Were they writing a book? Recording a podcast? Simply collecting memories for some sort of archive? To complicate matters, Shang and Njobe also decided they wanted to share the experiences of the other women who had attended Smith on the South African scholarship. Inspired by the lengths to which Black South Africans had to go—both physically and emotionally—in order to get a decent education, Njobe and Shang were determined to tell as many of the women’s stories as they could. But they didn’t know how to get started.

While they struggled to straighten out the details, Shang was introduced to a well-known Johannesburg-based media company executive. When he learned of Njobe’s mother’s remarkable story, and those of the South African Smith scholars, he volunteered his company’s services to film at Njobe’s home. It was an offer Shang and Njobe could not refuse. They loved the idea of telling the story with an audiovisual element, but it still didn’t occur to them that they were making a movie. “We didn’t call it a film,” Shang says now. “It was just ‘our project.’”

In 2016, Shang and Njobe finally filmed Njobe’s mother sharing her experience of fleeing South Africa and finding a way to continue teaching while in exile in Tanzania and Zambia. Since a film crew was already in place, they also captured three of the South African Smith scholars on camera on the same day. It was the first official forward step in their “project.” Sadly, Njobe’s mother passed away later that same year, and it would take two more years of mourning, healing, researching, and learning before Shang and Njobe decided that their “project” was going to be a film—a film that would shed light on and contextualize Smith’s South African scholarship program and give voice to the women whose lives were irrevocably changed because of it.

Filming in Johannesburg, South Africa, are, from left, producer Jane Dawson Shang ’82; producer and scholar Tandiwe Njobe ’94; scholars Heather Sonn ’95, Kholeka Mabuya ’96, and Vuyiswa Majova ’97; and director and editor Kate Geis.

In 1948, South Africa officially codified segregation and called its system apartheid. Based partly on the Jim Crow laws of the American South, apartheid made it illegal in almost every way for different races to mix in South Africa. And, as in the United States, separate did not mean equal. The quality of everything from schools to housing to job opportunities was based on a racial hierarchy wherein white South Africans received the best of everything and Black South Africans received the worst.

Even more insidious than the separation of the races in schools were the policies that regulated what Black and other non-white South Africans could learn. The curriculum for Black people was so limited and biased in favor of white supremacist doctrine that there was no way for a Black person to legally receive an effective education. What’s more, Black South Africans weren’t even allowed to attend the same universities as their white counterparts. They had very limited options for a good education. Taking a cue from American slave owners, the South African government knew an uneducated population was easier to control and oppress.

“After participating in this film, I am now able to look back at my time at Smith with a lot of pride and gratitude—proud of who Smith has molded me into, and gratitude for the support, encouragement, and opportunity to attend Smith. I can tell you that Smithies are my peeps, and I would change nothing about my time there.” —Meagan Van Harte ’95

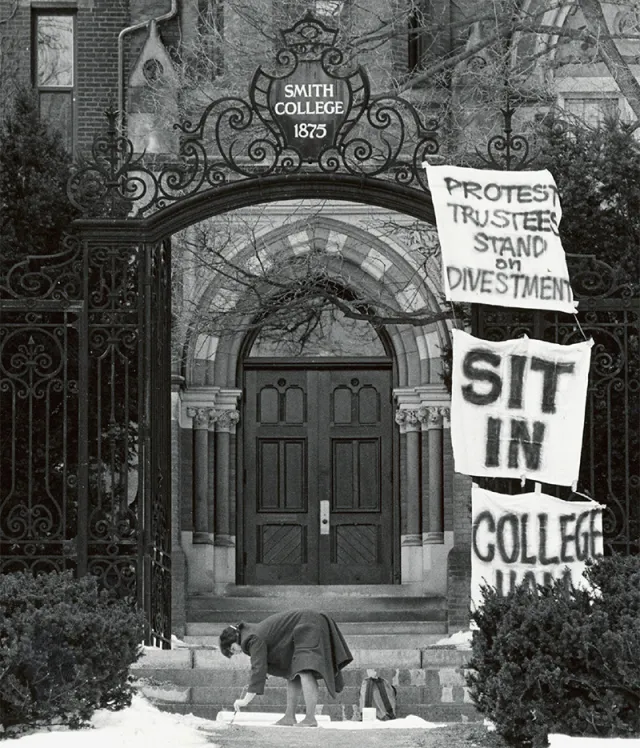

Meanwhile, in the United States, activists were lobbying American companies to divest from South Africa until it abolished apartheid. As protests in South Africa intensified, the demand for divestment in the United States grew more insistent as well. Large American companies with a global reach, including Coca-Cola and GM, were publicly targeted to divest, but so were American colleges and universities that had investments in these very same companies. No business or institution that had economic ties to South Africa was off the hook, including Smith College.

At the time—the early 1980s—many American colleges and universities were trying to do their part to help South African college students disadvantaged by apartheid by offering them scholarships to study in the United States. A consortium of American institutions called the South African Education Program (SAEP) even facilitated the placement of such students in American colleges and universities.

A 1986 protest at College Hall demanded that Smith divest from South Africa. Photograph by Gabriel Cooney

Peter de Villiers, a native South African who joined the Smith faculty in 1979 and is now a professor emeritus of psychology, was watching all of this unfold. As the chair of Smith’s newly formed faculty committee on international students, de Villiers says Smith joined SAEP but never received any South African students because the program primarily sponsored male graduate students interested in business or technical fields.

De Villiers knew that simply participating in SAEP was not going to bring South African students to Smith. He was particularly adamant about this and took his concerns to Jill Ker Conway, then the president of Smith. He wrote her a memo that read, “We will not get students from this program. If you want students from South Africa, you need to recruit them directly.”

As de Villiers remembers it, Conway had a lot to consider when it came to South Africa. Students and faculty members alike were demanding that Smith divest from companies that did business in the country. Meanwhile, the college’s trustees were wary of taking any actions that would diminish the school’s endowment. As Smith’s first woman president, Conway knew everything she did would be heavily scrutinized, and there were several stakeholders she needed to appease.

De Villiers recalls, “President Conway came to me and asked, ‘Can we really do this? Can we recruit young women directly from South Africa ourselves?’”

He didn’t pause before saying yes because he had a secret weapon in his back pocket: His father was a well-respected local minister in South Africa who sat on the board of the famous Inanda Seminary, one of the oldest schools in the country for Black South African girls. De Villiers knew that with his father’s connections, Smith could find students who would jump at the chance to come to Northampton.

With that problem solved, Conway had to figure out how to pay for a comprehensive scholarship that would fully fund all four years of the girls’ education and provide air transportation to and from South Africa.

To convince the college’s trustees to come up with the money for her ambitious plan, de Villiers says, Conway told them that since they had not yet decided whether to divest, the college was going to use the money it was earning from South African industries to educate its citizens. She then persuaded the trustees to set aside a chunk of money to form the South African scholarship program. It was thanks to Conway, de Villiers says, that the program came to fruition. A short time later, the first two scholars arrived in Northampton.

It was 1986, and the scholars were welcomed by de Villiers and his wife, Jill, who is now a Smith professor emerita of philosophy and psychology. For the next five years, de Villiers says, his father was instrumental in recruiting students from South Africa for the program, and he himself acted as both an academic adviser and a mentor to the women coming from his home country. As word spread about the scholarship, recruitment efforts widened across South Africa, more Smith professors got involved in advising and mentorship, and more South African schools started encouraging their students to apply.

“This film allowed me to pay homage to Sophia Smith’s vision of educating women in an environment that enables excellence. That vision she had all those years ago has created a cohort of women in the world that are at the fore of changing nations, communities, and families. If I were to do it again, I wouldn’t change a thing, because Smith is the reason I am and how I became.” —Vuyiswa Majova ’97

When, in 1990, Nelson Mandela was finally released from prison, the scholarship program continued. And when South African universities slowly started allowing Black students to enroll, Smith still continued the program, knowing equality in education wasn’t going to happen overnight. It wasn’t until 1994, when Mandela became president, that the trustees and President Conway’s successor, Mary Maples Dunn, decided to roll the South African scholarship monies into the college’s greater international student scholarship fund, effectively ending the program.

If you didn’t attend Smith between 1986 and 1994, you may have never known about the South African scholarship program, why and how it was created, and the women who came to Smith because of it. It might have been a forgotten piece of Smith’s history if Njobe and Shang hadn’t decided to tell the story in Where I Became.

When they started filming in earnest in 2018, neither Shang nor Njobe had made a movie before. “I didn’t realize how courageous and bold we were at the time, because we really had no idea what we were doing,” Njobe says. What they lacked in technical skills, however, they made up for with the conviction that the story they were trying to tell—that of a particular moment in history when a small college took a stand against injustice and changed the lives of 16 women in the process—needed to be told. In true Smith fashion, the two women decided they would figure it out as they went along. But it wasn’t easy, especially since Shang was now living in the United States and Njobe was still in South Africa.

Njobe and Shang divided tasks, making use of their strengths and locations. Shang dug through the Smith College Archives to find information about the scholarship’s origins and key figures. Meanwhile, Njobe got busy contacting the South African scholars and convincing them to revisit their Smith experience on film and reflect on how it changed their lives. Ultimately, the two were able to highlight 14 of the 16 scholarship recipients in the movie (two declined to participate for personal reasons). The voices of these women—who willingly left behind their families, friends, and culture in order to get a college education—are at the emotional heart of the film.

To interview the scholars, their family members, and current and former Smith faculty and staff, Njobe and Shang had to crisscross the globe, filming in South Africa, Northampton, Boston, and New York City. Luckily, they wrapped up their interviews in January 2020, right before the world shut down because of the COVID pandemic.

Shang says they leaned on Smith’s film and media studies program whenever they needed help. Indeed, two recent graduates, Council Brandon ’20 and Zoe Dong ’18, served as associate producers on Where I Became. And it was through Smith connections that Shang found the film’s director, Kate Geis, an Emmy Award–winning documentarian who lives in Northampton.

“It was a privilege to listen to the stories of these women,” Geis says. “And I hope it is empowering for the audience who sees the film. I think the most important lesson in their success is how the scholars supported each other as students, and how they continue to do that in their lives today.”

“I left South Africa at a time of much upheaval and unrest. I was initially angry, uncertain, and displaced. The film offered a balanced reflection of how I discovered myself at Smith in the books, resources, discussions, engagements, interactions, experiences, and relationships. It is a bigger, more important part of my life than I had previously understood.” —Heather Sonn ’95

At the beginning of their journey, Shang and Njobe thought they were making a movie about a group of South African women who came to Smith College on a special scholarship program. Their mission expanded when they realized that what they were really doing was making a movie about the revolutionary and radical act of providing a free education in the face of oppression. At its core, Where I Became is a love letter to Smith, a thank-you to an institution that made good on its promise to educate women and redress the wrongs of society. “I think deep in our hearts we want all Smithies to see Where I Became and be proud,” Shang says.

Where I Became is also a film for South Africans to take pride in, Njobe says. Although she was initially worried that a South African audience might find the story disconnected from the reality of the many South African people who never had the opportunity to study at an American college or university, she now feels differently.

“From a South African point of view, it’s a piece of our history,” Njobe says. “The film shows something positive that came out of something that was very negative. It’s so human on so many levels, and we think it can reach anyone who has a dream.”

The movie has already won a number of awards at film festivals around the globe, including Best International Documentary at the 2022 Hollywood North Film Awards. At press time, Njobe and Shang were in the process of finalizing a partnership with PBS to show Where I Became on local public television stations across the United States in the fall of 2023.

“We’re excited to see the opportunities that this film has,” Shang says. “We really want it to soar.”

Lori L. Tharps ’94 is a journalist, author, and creative writing coach. The host of the Read, Write and Create podcast, she lives in the south of Spain with her family.

The Incredible Story of a Little-Known Slice of Smith History

A Special Series

PART 1: ‘Where I Became’

A new documentary brings to light the story of an apartheid-era program that gave Black South African women the opportunity to study at Smith.

PART 2: Full Scholarship, Full Potential

An interview with one of the women who benefited from Smith’s South African scholarship program.

Jane Dawson Shang ’82, left, and Tandiwe Njobe ’94 were photographed at Constitution Hill, a national heritage site in Johannesburg, South Africa. Photograph by Lexie Knight