‘Dear Chums...’

Alum News

Published June 13, 2017

Bunny wrote the first entry in the newly purchased leather-bound blank book. She pasted in a photo of herself and sent the book to Binger, who added her bit and sent it to Andy, who sent it to Edie, who sent it to Piglit.

On it went until all 11 “Deweyites”—dear friends from Dewey House, class of 1938—had weighed in with a newsy letter about life since they parted ways at graduation. Then they started over: 30 letters over seven years, from 1938 to 1945. A sort of epic email chain, long before email.

We know all this now because in 2012, Carol Teel Isenberg—daughter of one of the Deweyites, Marjorie Rice Teel, aka Binger—stumbled on The Book in a forgotten box. “I started to read it thinking this would be a good way to pass the time,” Isenberg recalls. “It turned out to be so much more than that.”

Fragile and timeworn, The Book presented something of a puzzle: a bulging compendium of handwritten letters, some poems, one play, many photos, plus a bewildering array of in-jokes, maiden names, married names and the kind of sporty nicknames and slang one seldom hears anymore. To the class of 1938, the whole world was “nifty,” as in nifty jobs, nifty sights, nifty opportunities, even nifty marriages. Luckily for history, Isenberg is a determined sort who’d long taught English in middle school. “So I have much experience deciphering cursive,” she says.

Thus armed, Isenberg slowly typed the letters and sent copies to the descendants of the other 10 classmates. The final Deweyite, Anne Dalrymple Hull, who went on to become a trustee at Smith, died in February at 100. [See her obituary on page 67 of the Summer 2017 SAQ.] To her classmates, she was Andy.

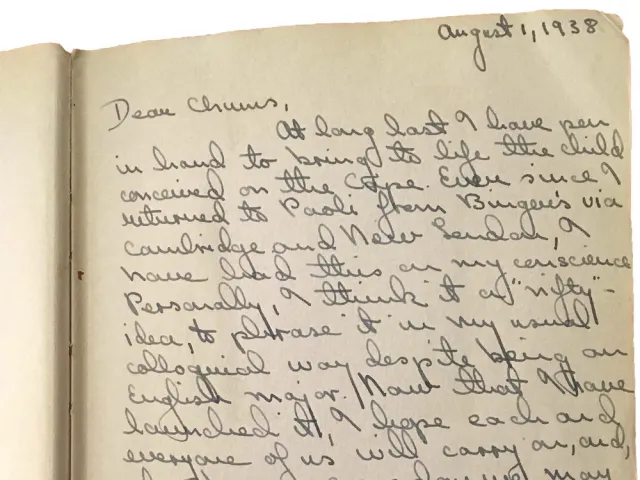

Today, The Book rests in a box in the Smith College Archives, a safe home for a charming, revealing time capsule of a generation. So how did it all begin? The Deweyites cooked up the idea during a post-graduation Cape Cod get-together. Here’s the epistolary debut from Allison Sharp Hufnagel, aka Bunny. It’s dated August 1, 1938:

Dear Chums,

At long last I have pen in hand to bring to life the child conceived on the Cape. … Personally, I think it is a “nifty” idea, to phrase it in my usual colloquial way despite being an English major. Now that I have launched it, I hope that each of us will carry on, and who knows someday we may have a very valuable book or books. After all, Dewey House of ’38, there will no doubt spring a genius or at least one or two of fame.

The early letters—before World War II begins, and the weddings and babies arrive—record their carefree lives. Going on dates, playing tennis, hitting the nightclubs, living with parents. Many describe how they cobble together paying work. Binger was a nanny that first summer. By day, she fed the children, “observing all the rules of diet from Hygiene II,” she cracks. At night, “while they were peacefully dreaming of the Bobbsey Twins at Snow Lodge, I could go out and have my fun.” Dodo (Doris Lewis Hirsch) lands a job at Mademoiselle: “I’ve tried so hard to be the smart young woman … [wearing] highly uncomfortable—but tebbly, tebbly modish—shoes, and the new orchid make-up.”

As 1940 arrives, the classmates buckle down. Edie (Edith Blakeslee Phelps) begins teaching history at Riverdale Country School for Girls (eventually to become headmistress at Dana Hall). Bunny is getting an M.A. in public administration at American University. And Katharine Swift Almy writes from Cornell Medical School: “Besides peering through a microscope, I have learned to approach the bedside with a determined manner, tap people’s backs and listen through the stethoscope.” (She would go on to become a professor of clinical psychiatry at Dartmouth Medical Center.)

Anne Dalrymple Hull, left, included her Ivy Day photo. Right, Alice Dean Lightner in 1941 wrote of switching from teaching to learning business skills.

Then, the war. In 1940, Andy writes, “At present my energies are concentrated on the Belgian Relief Fund. Come see me at 328 Park Avenue and help knit for the refugees!” Others marry servicemen—wedding photos with many Deweyite bridesmaids crop up—and find themselves living near Fort Bragg or in Washington, D.C.

Jean Cohen Fink gets a job in Manhattan as a receptionist for a Dutch refugee—who may or may not be a spy. In January 1942, she takes a moment to observe the speed of personal and historical change:

When I last wrote, September 16th, 1938, I was studying shorthand. Since then, eight of us have gotten married, New York has lived through a World’s Fair, the United States has embarked upon a 3rd term President and a 2nd World War.

By the last letter, in September 1945, The Book fills with baby pictures, as the 11 women busy themselves with growing families in a world newly at peace. The Deweyites had 32 children among them, and their families now cherish their own typewritten copies of The Book, thanks to Carol Isenberg’s meticulous work.

“The Book brought my mother back to me,” Isenberg says. “It was a miracle that it surfaced. For all of the families and for the Smith College community, well, I think it was meant to be resurrected.”

The “nifty idea” may have run its course after seven years, but the friendships did not. Over the decades, this group of spirited women continued to gather for reunions, and shared deep, close ties to the ends of their lives.

Freelance writer Katharine Whittemore recently became a senior writer in the Amherst College communications office.

This story appears in the Summer 2017 issue of the Smith Alumnae Quarterly.

Allison Sharp Hufnagel ’38, top row, second from left, started The Book by writing to 10 Dewey House classmates.