Introducing the Drone Thinking Initiative

Introduction

Project Phases

Prior to doing anything else, we set up our team structure. Together we came up with a list of goals to be reviewed and edited each week, as well as different roles for each of us to take on throughout the project. Amanda was assigned as the task master, making sure that we stayed on topic throughout the assignment. Zoe was made the gadfly, the person who would continually question the decisions made. Alex, the deadline coordinator, was in charge of making sure that we got things done on time. She was also the resident drone expert. Matt, the “love doctor,” made sure that everyone was feeling happy and satisfied with the work level. Finally, Cherry the mediator/assistant kept track of everything that we were doing.

After learning about our project and interviewing Jon, we hit the ground running. We started off Deep Dive 3 with a mini-test series, taking the key points from our conversation with Jon and focusing on safety, public opinion, and access in relation to UAVs. Our team began ideating, thinking of ideas from an “inflatable drone tent” to a “drone 5K.” Nothing was too silly for our first ideation; we just wanted all of our ideas to be represented. We used creative constraints to stoke our process until we decided that we needed to move on to prototyping. Recalling our impressions from interviewing Jon, we zeroed in on one of the biggest problems surrounding UAV usage: public opinion.

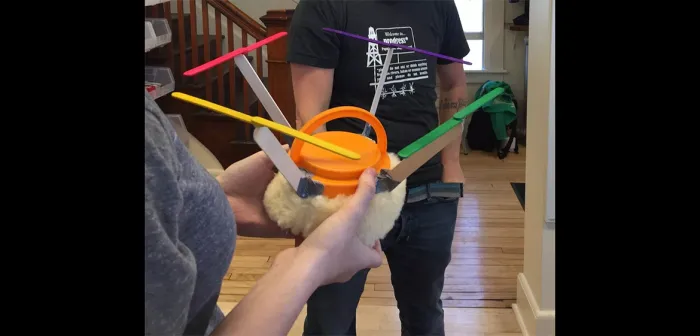

Looking at all of our ideas, we tried to choose one that would help expose people to drones in a positive way. For this round, we came up with the soft drone. The soft drone was a padded, colorful UAV that would not only be safer to fly around people but also friendlier-looking than some of the more sinister drone models on the market. After creating our soft drone, we asked two testers to tell us what feelings it evoked and how they would react if they saw it in the sky. Both had positive and tender impressions of the soft drone, describing its color and wooly texture as toylike. They think the appearance of a drone influences how it gets perceived. The testers both mentioned that more of their concerns were associated with the political uses of drones, such as surveillance or military. The scenarios they envisioned themselves potentially using a UAV included site investigation and mapping, and they felt it would be less concerning if called by names other than the politically-charged “drone”.

After our two interviews, we met with our first main user, Eliana, a senior who has flown drones for research. We asked her about how she felt about drones, what it was like to learn how to use drones, and how she used drones at Smith. While she was hesitant about sharing some information, she helped us understand what the experience of flying at Smith was like – namely, mainly off Smith campus. Our talk with Eliana also emphasized the fineness of the line between recreational use and surveillance. Many times in our discussion, she asked, “Where is that line?” and “How is a drone different from a model airplane?”

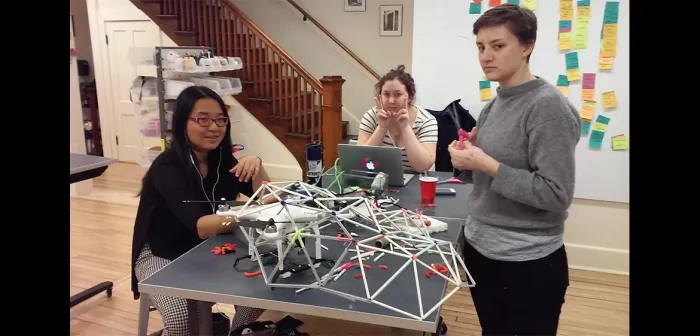

After our second round of ideation, we narrowed down our sticky notes to a pair of ideas that addressed our POV directly and also seemed reasonable to accomplish within a week. One of these ideas was to build a drone cage, similar to the “drone dome” that Jon had mentioned several times during our meetings with him, that students could stand inside to fly a UAV in. The other idea was to build a sort of “crab cage”, which would be attached to the drone as it flew instead of limiting the space in which it could fly. The team was torn between the two options, but in terms of feasibility, the crab cage model was selected because the smaller scale seemed more achievable with the materials we had available to us.

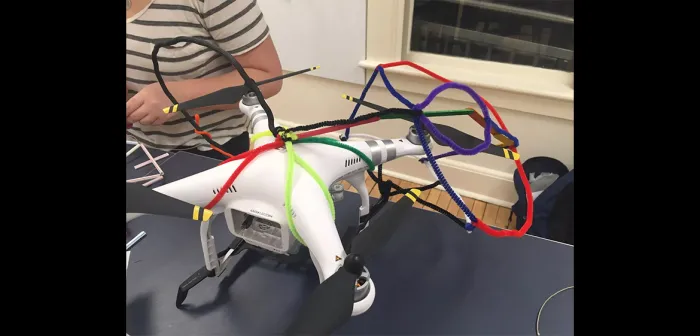

Our first attempts at modeling this cage started with popsicle sticks and pipe cleaners. However, these resulted in a relatively fragile prototype, and we realized we needed a sturdier model if we were going to accurately prototype anything that could be used to protect people from the propellers of the UAV. (As the fastest-moving exposed parts of the drone, the propellers are often the most hazardous aspect.)

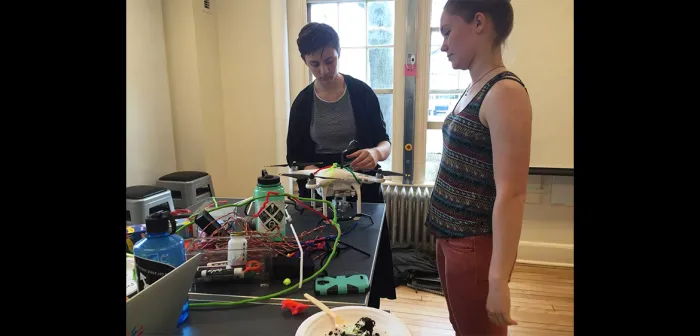

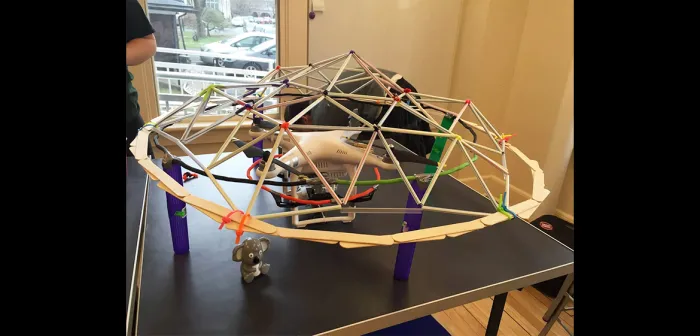

Another of the attempts at this crab cage model used straws threaded together using string into a rudimentary geodesic dome. Jon was getting his wish after all! Although this model was flimsy at first, we reinforced it using pipe cleaners at the intersection points, and gave it further structure with a stabilizing hoop of popsicle sticks at the base of the dome. One of the issues we encountered with this model, however, was how to attach this dome to the UAV.

After looking through all of the bins in the prototyping cart, we found a potential solution in the landing gear that came with the drone. This landing gear could be clipped on to the frame upside down, such that the extended legs splayed upward. A hoop could then be attached to the legs, surrounding the UAV. A second, larger hoop could be connected to this, providing a base upon which to place the dome.

In the second test series, the team moved towards addressing the social aspect of UAVs on campus.

Jon had an incredible passion for UAVs that we didn’t see in the wider student body. How could we make that a little bit more contagious? We wanted to show people the potential of UAVs.

With that in mind, we made our new POV: “A student is apprehensive (or even a little bit afraid) needs encouragement/a push out of their comfort zone in order to discover what drones have to offer.”

We ideated (in two separate groups due to late-in-the-semester logistical concerns). Our finalists: a drone matching survey, drone TedX talks, and a J-term course. Several other ideas, including a drone art competition and increased visibility of drone footage around campus, were subsumed into these candidates.

The team chose the J-term course to prototype. It had the fewest barriers to entry for people new to UAVs, combined with the most hands-on experience, and so we assessed it as more likely to reach people and create genuine enthusiasm for artistic and scientific UAV use. After a break for dinner, we regrouped and created a syllabus. We considered difficulties such as “adverse weather conditions” and “is it actually fun.”

We ended up with a plan for a five-day, one-credit J-term course: IDP 000J, Fun with Drones. IDP 000J would lead students through learning to fly a drone, pre- and post-flight drone care, software operation, and social issues. The final project of the class: a short drone-filmed video that could be used for UAV promotion efforts on campus.

After completion of the course, students would be able to check out UAVs from the Spatial Analysis Lab. In case of inclement January weather, the course could be taught in the ITT.

POV: Creative students seeking a new technology need an introduction to drone technology (and all its baggage) in a liberal-arts fashion in order to understand the responsibilities tied to safe drone use.

Website: https://smithfunwithdrones.wordpress.com

The J-Term syllabus was met with such enthusiasm from our testers that it lurked in the back of our minds as we began work on our final prototype. How could we improve on it? As we ideated, post-its along a certain theme kept popping up: Drones in the film department. Outreach to landscape studies. We realized that the J-term course was only the beginning. If we taught Smithies how to fly, they needed to be able to use their new ability for more than just a novel hobby. To make that happen, we needed to go beyond introducing UAVs to just students.

If we could help professors learn about drones and find ways to incorporate them into their classes and research, it would be key to establishing a positive UAV presence on campus. We briefly touched upon the concept of holding faculty workshops, in order to introduce professors to drones as non-threateningly and creatively as possible. It was our hope that, if a faculty member enjoyed learning about UAVs and saw potential to expand their own work in this way, they would share the knowledge with their students and foster learning about them on campus in a more organic way.

But, with four days remaining, how would we prototype-to-interact a workshop – not to mention all the other valuable parts of the outreach we were imagining? In the interests of both feasibility and prototyping experience, we chose to pivot.

We developed a website to describe potential action plans, gather resource materials, and have a central location to share information with any interested parties. To increase the amount of interaction generated by the website, we drafted a short email and shared the site with several professors across campus, in key departments that we saw potential for drone use. We asked for feedback to gauge whether professors found this site intriguing, and whether it sparked interest in learning more about how UAVs could be used, in their work or otherwise on campus.

A Look at the Process

Conclusion

How did our teamwork work out?

Matt felt as if he fell into his role as the “love doctor” fairly well. Although he was not present for a large portion of the project due to sickness and being located at a distance from campus, he was able to check in with the group and dissolve tension at a few key moments. At one moment in particular, when the group was stressed over approaching deadlines, Matt was able to get Amanda to talk about how she felt individuals differed in their levels of input and availability levels. One thing that he wished that he did more was check in with everyone individually rather than as a group and talk about how they felt in general.

Zoe learned how to go with the flow in this group, something she’s previously struggled with. She would have liked to have found a better balance between facilitating others’ plans and directly contributing- she may have sometimes gotten too far away from being controlling- but, overall, she’s glad that she could be a helpful pair of hands in the execution of the team’s ideas. One moment she’s proud of: when the group was deciding between prototyping the tiny drone dome and a larger structure, everyone but Matt was pro-dome, and we almost moved ahead then. But Zoe helped the group pause and make sure that we were united in our reasoning and that Matt had something to be enthusiastic about in his second choice. In her assigned role (mildly criticizing everything), her personality helped her perform admirably. She’s very grateful for the shared level of dedication to the project and the open communication throughout the group, and for the experience of ideating and creating with her supportive teammates.

While it went against every strand of her code, by the end of the project Amanda was learning how to let others lead while still staying present in the group. Even though she wished that she learned a bit more about the components of making a movie, she felt that she improved in the listening department since Deep Dive 2. As for the group, Amanda thinks that the team grew closer each day and that they became more and more comfortable with the rapid design cycle as time went on. She also believes that the team did well with recognizing failure and moving on: instead of focusing on the technicalities of a prototype (ie. the drone dome couldn’t actually attach to the drone) the group would look at the overall main ideas of a prototype and try to incorporate them into their next design process. The group challenged Amanda to let go a little more and to think about designs in different ways. While each person in the group had an entirely different personality, the team used our different backgrounds to grow and expand our ideas rather than to divide us into cliques – something Amanda is proud to be a part of.

Cherry is proud of the progress the group has made in short amount of time, though she hoped that she could have made more contributions beyond bringing in more insights through extensive research, and taking photos and notes. Though she had the role of mediator and assistant, she learned more from her teammates: how to efficiently communicate with and interview users and clients from Amanda, how to clearly structure a story and express ideas (both verbally and visually) from Zoe, how and where to find relevant information from Alex, and how to keep the group energized from Matt. Cherry will keep following up on the topic of drone usage and perception after graduation, as this project has not only led her into the world of drone film, but also enabled her to see the swelling popularity of drones in her hometown in southeast China, where the toyification and lowered entry standard caused by DJI makes drones more accessible to the public but also creates more safety concerns.

Alex felt that, although the team initially had some difficulty building up momentum on the project, meetings were generally quite productive and successful. Making use of the timers in Capen Annex made for especially fruitful meetings, when the time was broken up into short increments with clear objectives. A few reminders here and there kept the team on track to prototype in a timely manner, while still respecting everyone’s need to get other work done at the same time. No time was wasted in getting the portfolio started; the document was created on the day the project officially began, with the team well aware of how much easier it would be to write it, bit by bit, as a joint effort along the way. And during the final crunch time for pulling the video together, the whole team did a fantastic job of “dividing and conquering” and delegating amongst ourselves to get everything done. Matt and Alex went to capture the final video footage, while Cherry, Amanda, and Zoe furthered the script, and once it was time to record the voiceover, Matt, Alex, and Cherry set out to the CMP, while Zoe and Amanda focused on pulling more of the visuals together. All things considered, we stuck to our POVs and generated a final prototype and a video that the whole team was proud of – right on time.