|

Virginia Woolf

A Botanical Perspective Presented by the Botanic Garden of Smith College |

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

Books

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

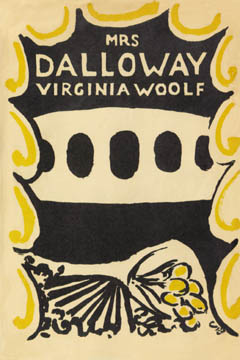

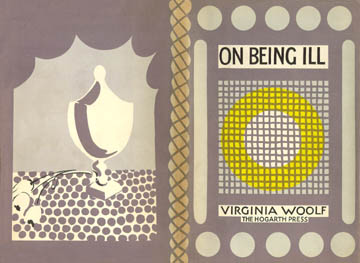

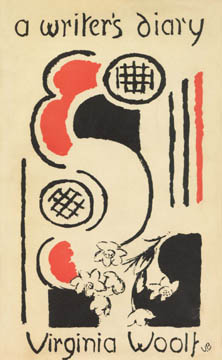

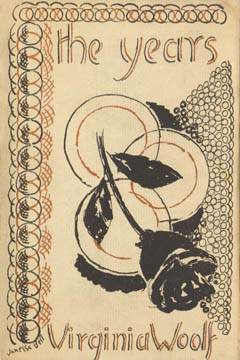

Reproductions of covers of first editions

published by the Hogarth Press, designed by Vanessa Bell. From the Frances Hooper Collection of Virginia Woolf Mortimer Rare Book Room, Smith College. |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. . . The whole tree hummed with the whizz they made, as if each bird plucked a wire. A whizz, a buzz rose from the bird buzzing, bird vibrant, bird blackened tree. The tree became a rhapsody, a quivering cacophony, a whizz and vibrant rapture, branches, leaves, birds syllabling discordantly life, life, life, without measure, without stop devouring the tree. . . . . . Between the Acts (1941)

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. . . one might rise and see for oneself, the house all empty, the doors standing open, only the wood pigeons bubbling with content and the hum of the threshing machine sounding from the farm. "What did I come in here for? What did I want to find?" My hands were empty. "Perhaps it's upstairs then?" The apples were in the loft. And so, down again, the garden still as ever, only the book had slipped into the grass.

But they had found it in the drawing-room. Not that one could ever see them. The window panes reflected apples, reflected roses; all the leaves were green in the glass. If they moved in the drawing-room, the apple only turned its yellow side. Yet, the moment after, if the door were opened, spread about the floor, hung upon the walls, pendant from the ceiling - what? My hands were empty. . . Haunted House (1944) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| . . . About this time a firm of merchants having dealings with the East put on the market little paper flowers which opened on touching water. As it was the custom also to use finger-bowls at the end of dinner, the new discovery was found of excellent service. In these sheltered lakes the little coloured flowers swam and slid; surmounted smooth slippery waves, and sometimes foundered and lay like pebbles on the glass floor. Their fortunes were watched by eyes intent and lovely. It is surely a great discovery that leads to the union of hearts and foundation of homes. The paper flowers did no less. It must not be thought, though, that they ousted the flowers of nature. Roses, lilies, carnation in particular, looked over the rims of vases and surveyed the bright lives and swift dooms of their artificial relations. . . . But real flowers can never be dispensed with. If they could, human life would be a different affair altogether. . . Jacob's Room (1922) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

| Kew Gardens | Kew and Smith | |||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

...There were flowers: delphiniums, sweet peas, bunches of lilac; and carnations, masses of carnations. There were roses; there were irises. And then, opening her eyes, how fresh like frilled linen clean from a laundry laid in wicker trays the roses looked; and dark and prim the red carnations, holding their heads up; and all the sweet peas spreading in their bowls, tinged violet, snow white, pale-as if it were the evening and girls in muslin frocks came out to pick sweet peas and roses after the superb summer's day, with its almost blue-black sky, its delphiniums, its carnations, its arum lilies was over; and it was the moment between six and seven when every flower-roses, carnations, irises, lilac-glows; white, violet, red, deep orange; every flower seems to burn by itself, softly, purely, in the misty beds; and how she loved the grey-white moths spinning in and out, over the cherry pie, over the evening primroses! . .

Mrs. Dalloway (1925) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

. . . Let us examine the rose. We have seen it so often flowering in bowls, connected it so often with beauty in its prime, that we have forgotten how it stands, still and steady, throughout an entire afternoon in the earth. It preserves a demeanour of perfect dignity and self-possession. The suffusion of its petals is of inimitable rightness. Now perhaps one deliberately falls; now all the flowers, the voluptuous purple, the creamy, in whose waxen flesh the spoon had left a swirl of cherry juice; gladioli; dahlias; lilies, sacerdotal, ecclesiastical; flowers with prim cardboard collars tinged apricot and amber, all gently incline their heads to the breeze-all, with the exception of the heavy sunflower, who proudly acknowledges the sun at midday and perhaps at midnight rebuffs the moon. There they stand; and it is of these that human beings have made companions; these that symbolise their passions, decorate their festivals, and lie (as if they knew sorrow) upon the pillows of the dead.

On Being Ill (1930) |

|||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

| ...It was raining. A fine rain, a gentle shower, was peppering the pavements and making them greasy. Was it worth while opening an umbrella, was it necessary to hail a hansom, people coming out from the theaters asked themselves, looking up at the mild, milky sky in which the stars were blunted. Where it fell on earth, on fields and gardens, it drew up the smell of earth. Here a drop poised on a grass-blade; there filled the cup of a wild flower, till the breeze stirred and the rain was spilt. Was it worth while to shelter under the hawthorn, under the hedge, the sheep seemed to question; and the cows, already turned out in the grey fields, under the dim hedges, munched on, sleepily chewing with raindrops on their hides. . .

The Years (1937) |

||||||||||||||||||||||

| © 2003 Botanic Garden of Smith College | ||||||||||||||||||||||