Seeing Psychology Happen: Prof. Peake on His Award-Winning ‘Marshmallow Test’ Studies

Research & Inquiry

Published July 13, 2015

On the surface, the experiment seemed simple: Would the children at Stanford University’s Bing Nursery School eat the marshmallow in front of them, or wait so that they could earn promised extra treats?

Yet, the impact of that study—launched by psychologist and professor Walter Mischel in the late 1960s and popularly known as the “marshmallow test”—has been far ranging, shaping scientific understandings of child psychology, education and human development.

Smith psychology professor Philip Peake got involved with the “marshmallow test” as a graduate student at Stanford in the late 1970s and has been working on follow-up research ever since. For achieving groundbreaking results in their studies of delayed gratification, Peake, Mischel and a third colleague, Yuichi Shoda, now a professor at the University of Washington, have received a 2015 Golden Goose Award.

Founded in 2012, the awards recognize federally funded research that has had a significant impact on society.

The power of the “marshmallow test” has been “enormous and unexpected,” writes Julia Smith in a post on the Golden Goose Award website. Follow-up studies by Peake, Mischel and Shoda have shown that four-year-olds who are able to exercise self-control in waiting to eat the marshmallows perform better academically and socially and are better at handling stress as they grow older.

“These discoveries in behavioral research have changed the way we think about how self-control is achieved: from brute-force stoic willpower to intelligent strategies that can be practiced and enhanced,” Smith writes. “The findings have direct implications for how we approach parenting and educating young children, help people maintain good health, and even save more effectively for retirement.”

Peake—who, with the help of his Smith students, is now archiving the “marshmallow test” data at Smith—has been working with neuroscientists, economists and others who want to explore how the findings can be applied to their fields.

Here’s what Peake had to say about the origins of the “marshmallow test” and what it means to have won a Golden Goose Award.

What led you to start studying self-control behaviors in children?

Peake: “The initial study was begun at Stanford back in the 1960s by my mentor and now colleague, Walter Mischel. He’d been interested in delayed gratification for years. Most of the previous studies on that topic had focused on choices: Which would a kid prefer, one treat now or several treats a week later? What Mischel’s paradigm did that was different was to allow the preschoolers to act out that contingency, to actually engage with the process of delay. He was interested in the contextual factors that would affect kids’ behavior, as opposed to just their preferences.”

Who came up with the idea of using a marshmallow as the reward?

Peake: “Well, marshmallows are a very vivid example, but they aren’t the only thing we used in the study. We used pretzels, cookies, M&Ms. Some of the experiments didn’t even involve food—we used ‘good player’ award stickers, for example. One of the beauties of this paradigm is that it was done with four-year-olds. It turns out, there are a lot of interesting things happening developmentally when kids are that age. That’s when they are beginning to develop a set of skills known as executive function; the ability to take instruction and see things from other people’s perspective. We didn’t know all of that at the time the study began.”

Why is delayed gratification important?

Peake: “It’s a key aspect of self-control which is believed to be linked to all kinds of positive behaviors in life. Over the years, our findings have made their way into all kinds of fields, including education and influencing curriculum development. Self-control is a key component of emotional intelligence. This work represents a fundamental shift in how people help kids implement willpower. As opposed to the idea of toughing it out or ‘just saying no,’ this research suggests that if you watch kids, they’re actually using adaptive strategies—turning their attention away from the marshmallow, playing games, singing songs, looking in mirrors. When you observe the behavior on the surface, it is really cute. But when you analyze it, you see that it’s an adaptive, flexible strategy that kids are using to deal with stressful situations. These experiments offer that rare moment when you can see psychology happening. You can see the struggle and the psychological processes of self-control.”

How did you decide to expand the initial study?

Peake: “Doing the follow-up was just curiosity at first. While conducting consistency research, I came across the data archive for the early “marshmallow test” experiments, and we began to organize it to see if it might include useful information. We realized many of the participants in the original studies were children of Stanford faculty then in local high schools. We decided to see if their early waiting might relate to their current well-being. Lo and behold, we found these interesting relationships in how kids were performing academically and in their social life—their coping skills. In the 1990s, we did a second follow-up with kids who were then in their late 20s. That work was all done by my Smith students. And in 2003, we did a third follow-up of kids in their 30s. As the study has progressed and become recognized, researchers have come to us with new questions, and the project has become interdisciplinary. I’m now working with economists and neuroscientists who are interested in these results. The next phases of our work will examine participants as they move into later stages of their lives. It’s an exciting challenge that will open up all kinds of questions for Smith students to pursue.”

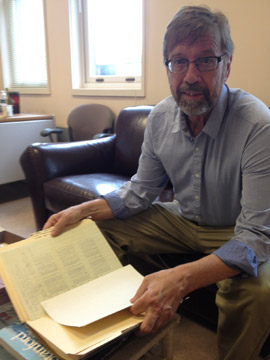

Psychology professor Philip Peake displays some of the original data from the award-winning ‘marshmallow test’ studies that will be archived at Smith.

Many of the subjects in the initial experiment were children of Stanford faculty members. How does their status as relative ‘haves’ factor into analyzing their later successes or failures?

Peake: “It’s an interesting research problem for us. The fact that we’re dealing with so many kids from similar socio-economic and educational backgrounds works against us statistically. We have since completed experimental replications in other settings, including the Knowledge Is Power Program public charter schools in the Bronx. Our work has also been directly replicated in a sample of children in China, and different researchers are finding similar results with alternative measures of self-control. We’re doing a replication study here at Smith with kids in the study who are now college-aged. We don’t miss opportunities to verify our results.”

What else is important to know about the marshmallow test?

Peake: “Working with these data makes one keenly appreciative of the cultural changes that have happened over the course of the research. As an example, when the study began in the 1960s, fully 95 percent of the mothers listed their occupation as ‘housewife.’ I am also impressed by the amazing shifts we’ve seen in the technologies we use to do this work. In the 1960s, everything was recorded on big pads of paper, and calculations were done by hand. Now, new tools and social media are allowing us to track and communicate with participants in ways we never would have imagined. Walter Mischel is about to retire, so the data will be coming to Smith and will be archived at my lab. That’s something my Smith students will be working on over the next couple of years. It’s an extraordinary opportunity for them.”

What does it mean to have won the Golden Goose Award?

Peake: “The award is meant to be the flip side of the late U.S. Senator William Proxmire’s Golden Fleece Awards that were meant to ridicule the use of federal funds on what seemed like odd research. The idea behind the Golden Goose Award is to recognize federally funded research that may have looked odd to start with, but has had a major impact. The award will bring more recognition to our work, and more visibility. It’s expensive work to do, and as we move forward, we will be exploring alternative ways to fund it. The beauty of federal funding is that it allowed us to do stuff that was risky. We’ve had the freedom to explore quirky ideas. We’re hoping the Golden Goose recognition will attract donors who are interested in allowing us to continue in that spirit.”