| Governance

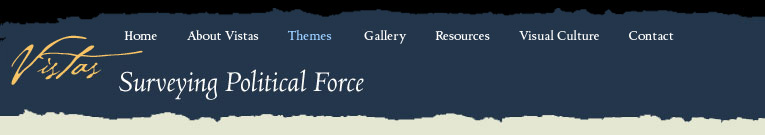

in Spanish America was, on the surface, a top down

affair. City life was punctuated by reminders of the

centrality of the king and his representative, the

viceroy. Across the whole colonial period, city dwellers

were called out from their homes by noisy processions

to welcome a new viceroy, celebrate the birth of a

royal heir or mourn the death of their king. These

events—surprising and irregular—were extravagantly

commemorated and they also afforded spectators a visual

lesson on politics.

The

position of participants in the parade signaled their

importance in this political hierarchy, even beyond

the elegance and color of their clothing or the weight

of their swords. Members of the Audiencia, the judicial

branch of the Spanish government, would ride grandly

on horseback, as would the Viceroy, while alcaldes,

or councilmen, might follow on foot. And the morning

after, city dwellers were again reminded of their

role in this system when tax collectors knocked at

their doors to have them foot the bill. The

position of participants in the parade signaled their

importance in this political hierarchy, even beyond

the elegance and color of their clothing or the weight

of their swords. Members of the Audiencia, the judicial

branch of the Spanish government, would ride grandly

on horseback, as would the Viceroy, while alcaldes,

or councilmen, might follow on foot. And the morning

after, city dwellers were again reminded of their

role in this system when tax collectors knocked at

their doors to have them foot the bill.

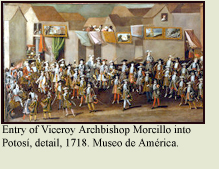

This

section of Vistas focuses on visible things

left by these shows of political power. Perhaps least

surprising are the portraits of kings, from painted

versions that adorned the walls of elegant houses

to engraved versions on coins that circulated from

royal mint to country market. Second in power to the

monarch were his appointed viceroys, whose portraits

mimicked those of the king. Yet images of the mighty

were not the most important ways in which political

power was made visible. Political power could be embedded

in and enacted through the use of maps of territory,

staffs of office and government palaces. These works

do not merely reflect the power resulting from governance.

Rather, these objects and visual displays had agency—that

is, leaders used pageants, buildings and paintings

to refresh their audience’s understanding of

the political hierarchy. While some scholars interpret

these events and objects as propaganda, foisted by

an arrogant ruling class onto the populace at large,

this represents a too-narrow view. In order to be

absorbed into visual culture and preserved over time,

staffs of office and royal portraits depended on a

willingness of the governed, as well as those governing,

to participate in the rituals that cleaved people

to rulers. This

section of Vistas focuses on visible things

left by these shows of political power. Perhaps least

surprising are the portraits of kings, from painted

versions that adorned the walls of elegant houses

to engraved versions on coins that circulated from

royal mint to country market. Second in power to the

monarch were his appointed viceroys, whose portraits

mimicked those of the king. Yet images of the mighty

were not the most important ways in which political

power was made visible. Political power could be embedded

in and enacted through the use of maps of territory,

staffs of office and government palaces. These works

do not merely reflect the power resulting from governance.

Rather, these objects and visual displays had agency—that

is, leaders used pageants, buildings and paintings

to refresh their audience’s understanding of

the political hierarchy. While some scholars interpret

these events and objects as propaganda, foisted by

an arrogant ruling class onto the populace at large,

this represents a too-narrow view. In order to be

absorbed into visual culture and preserved over time,

staffs of office and royal portraits depended on a

willingness of the governed, as well as those governing,

to participate in the rituals that cleaved people

to rulers.

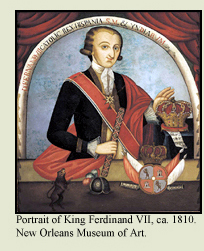

One

metaphor that runs through discussions of politics

and its visual expression is war, no doubt because

it was both the alpha and omega of political order:

wars of conquest preceded government, and wars followed

when government failed. In the early years of the

16th century, war and governance were inseparable.

The conquistadors, the first Spaniards to wrest governance

away from indigenous rulers in the Americas, were

hardened soldiers. Early viceroys, like Antonio de

Mendoza, likewise needed to wield the sword as well

as the scepter. In most cases, though, the powerful

were content merely to invoke the iconography of war,

rather than actually wage war. Devotion to Santiago

Matamoros, St. James the Moor-slayer, played a deep

and lasting role in Spanish America. Across the colonies,

his image, mounted upon a horse ready for battle,

was painted, sculpted, and, upon occasion, carried

into the streets during processions. One

metaphor that runs through discussions of politics

and its visual expression is war, no doubt because

it was both the alpha and omega of political order:

wars of conquest preceded government, and wars followed

when government failed. In the early years of the

16th century, war and governance were inseparable.

The conquistadors, the first Spaniards to wrest governance

away from indigenous rulers in the Americas, were

hardened soldiers. Early viceroys, like Antonio de

Mendoza, likewise needed to wield the sword as well

as the scepter. In most cases, though, the powerful

were content merely to invoke the iconography of war,

rather than actually wage war. Devotion to Santiago

Matamoros, St. James the Moor-slayer, played a deep

and lasting role in Spanish America. Across the colonies,

his image, mounted upon a horse ready for battle,

was painted, sculpted, and, upon occasion, carried

into the streets during processions.

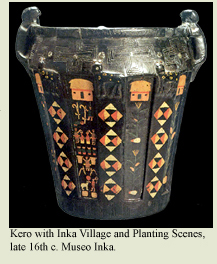

But

political power and the obligations of governance

were not just the province of Spaniards and Creoles.

From the time of the conquest of Mexico, Spaniards

built the colonial state upon pre-existing systems

of native governance. While the Spaniards gave indigenous

leaders new titles and rites of rule, they were reluctant—and

probably unable—to dismantle their political

systems completely. In the 16th century, many local

town governments were run by native men who conducted

meetings in their native tongues with little interference

or involvement from outsiders. And objects associated

with pre-Hispanic political and religious power, such

as drinking cups from the Andes known as keros, were

still exchanged as political gifts and displayed in

public feasts even as they took on new meanings and

imagery. Indeed, it comes as little surprise that

these objects did not remain static in their importance

because native systems of governance continued to

develop throughout the colonial period. But

political power and the obligations of governance

were not just the province of Spaniards and Creoles.

From the time of the conquest of Mexico, Spaniards

built the colonial state upon pre-existing systems

of native governance. While the Spaniards gave indigenous

leaders new titles and rites of rule, they were reluctant—and

probably unable—to dismantle their political

systems completely. In the 16th century, many local

town governments were run by native men who conducted

meetings in their native tongues with little interference

or involvement from outsiders. And objects associated

with pre-Hispanic political and religious power, such

as drinking cups from the Andes known as keros, were

still exchanged as political gifts and displayed in

public feasts even as they took on new meanings and

imagery. Indeed, it comes as little surprise that

these objects did not remain static in their importance

because native systems of governance continued to

develop throughout the colonial period.

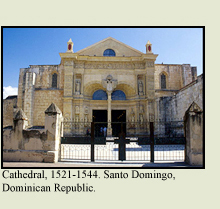

Many

objects and documents bind temporal political power

to divine power. Such unions had deep roots in Spain

and the Americas. In Spain, rulers were believed to

receive their right to rule through a contract with

the people that was sanctioned by God and the Catholic

Church. And likewise, the rulers of pre-Hispanic states

were held to have divine or semi-divine status. Cathedrals,

such as those in the major cities of Lima, Mexico,

Puebla, Santo Domingo and Antigua, were not strictly

buildings for prayer. They also housed the remains

of conquistadors and the masses celebrating the consecration

of kings and viceroys. And most cathedrals opened

their doors onto the central plazas of Spanish America’s

capital cities, sharing pride of place with other

prestigious government buildings. Many

objects and documents bind temporal political power

to divine power. Such unions had deep roots in Spain

and the Americas. In Spain, rulers were believed to

receive their right to rule through a contract with

the people that was sanctioned by God and the Catholic

Church. And likewise, the rulers of pre-Hispanic states

were held to have divine or semi-divine status. Cathedrals,

such as those in the major cities of Lima, Mexico,

Puebla, Santo Domingo and Antigua, were not strictly

buildings for prayer. They also housed the remains

of conquistadors and the masses celebrating the consecration

of kings and viceroys. And most cathedrals opened

their doors onto the central plazas of Spanish America’s

capital cities, sharing pride of place with other

prestigious government buildings.

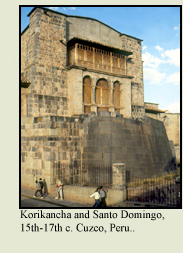

In

fact, residents of Spanish America really lived under

the domain of two overlapping governments, one run

by the Crown, the other by the Church. In many regards,

the two were inseparable. Early on, for instance,

the conquest of territory and political empire proceeded

hand-in-glove with the conversion of native people.

The physical and visual traces of this enterprise

remain. Just as Santo Domingo rises out of the foundations

of the Korikancha, many other churches were built

on top of the foundations of indigenous temples. In

addition, large monastic complexes were built under

the supervision of friars in the 16th century. This

same enterprise was still alive in the 18th century,

as missions were built in Texas and California. Across

the colonial period, the desire to evangelize and

civilize always bound Church and state. In

fact, residents of Spanish America really lived under

the domain of two overlapping governments, one run

by the Crown, the other by the Church. In many regards,

the two were inseparable. Early on, for instance,

the conquest of territory and political empire proceeded

hand-in-glove with the conversion of native people.

The physical and visual traces of this enterprise

remain. Just as Santo Domingo rises out of the foundations

of the Korikancha, many other churches were built

on top of the foundations of indigenous temples. In

addition, large monastic complexes were built under

the supervision of friars in the 16th century. This

same enterprise was still alive in the 18th century,

as missions were built in Texas and California. Across

the colonial period, the desire to evangelize and

civilize always bound Church and state.

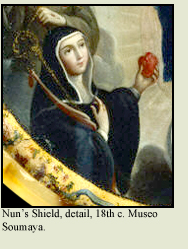

The

lack of political power was also conveyed through

the visual. Women carried parasols, not staffs; plantation

slaves wore few clothes. Most indigenous men were

forbidden to ride on horseback and carry swords, both

the distinguishing prerogatives of soldiers and gentlemen.Yet

the general lack of political power held by women

and native peoples should not be read as a perpetual

void. Women could wield political power within the

protective shelter of convents, where they could lead

communities, oversee the conduct of novices and control

the often-considerable sums that were communal assets.

Indigenous men, especially elite and educated ones,

could hold public office in their own communities,

head religious societies called cofradías,

and exert considerable sway in local affairs. The

lack of political power was also conveyed through

the visual. Women carried parasols, not staffs; plantation

slaves wore few clothes. Most indigenous men were

forbidden to ride on horseback and carry swords, both

the distinguishing prerogatives of soldiers and gentlemen.Yet

the general lack of political power held by women

and native peoples should not be read as a perpetual

void. Women could wield political power within the

protective shelter of convents, where they could lead

communities, oversee the conduct of novices and control

the often-considerable sums that were communal assets.

Indigenous men, especially elite and educated ones,

could hold public office in their own communities,

head religious societies called cofradías,

and exert considerable sway in local affairs.

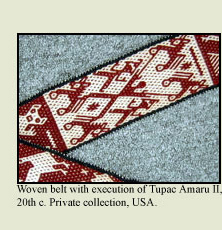

It

is the objects and buildings produced for the established

political institutions—the Spanish state and

the Catholic Church—that have been best preserved.

Still others outside this circle used the visual to

aid in their contests for political power. Rebel leaders,

for example, often commandeered the established visual

expressions of political power. When the Andean rebel

Tupac Amaru II first seized power in 1780, he staged

an elaborate public execution of the Spanish corregidor,

to show his take-over of the viceregal justice system.

He also came to refer to himself as the Inka, a name

that called up the specter of pre-Hispanic rulership.

That his rebellion did not succeed is, in certain

respects, just one piece of the story. For Tupac Amaru’s

ambitions and grisly demise were commemorated via

paintings and weavings like this 20th-century example,

as well as in written texts and oral narratives. It

is the objects and buildings produced for the established

political institutions—the Spanish state and

the Catholic Church—that have been best preserved.

Still others outside this circle used the visual to

aid in their contests for political power. Rebel leaders,

for example, often commandeered the established visual

expressions of political power. When the Andean rebel

Tupac Amaru II first seized power in 1780, he staged

an elaborate public execution of the Spanish corregidor,

to show his take-over of the viceregal justice system.

He also came to refer to himself as the Inka, a name

that called up the specter of pre-Hispanic rulership.

That his rebellion did not succeed is, in certain

respects, just one piece of the story. For Tupac Amaru’s

ambitions and grisly demise were commemorated via

paintings and weavings like this 20th-century example,

as well as in written texts and oral narratives.

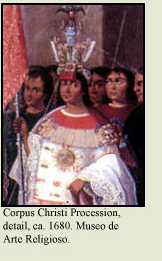

Such

evocation of the political order of pre-Hispanic empires

became integral to visual displays of power in Spanish

America. And it was the empires felled by the Spanish

conquest—the Aztec in New Spain, and the Inka

in Peru—that were most often evoked. To suggest

the unbroken progression of imperial governance, floats

and triumphal arches celebrating new Spanish kings

included images of the imperial Inka or alluded to

the royal Aztecs of the past. And on colonial feast

days in the Andes, elites who could trace their descent

from ancient Inka royalty proudly wore elaborately

embroidered tunics along with the maskapaycha,

a scarlet fringe across their foreheads that had once

been the crown of office of the supreme Inka.

Such

evocation of the political order of pre-Hispanic empires

became integral to visual displays of power in Spanish

America. And it was the empires felled by the Spanish

conquest—the Aztec in New Spain, and the Inka

in Peru—that were most often evoked. To suggest

the unbroken progression of imperial governance, floats

and triumphal arches celebrating new Spanish kings

included images of the imperial Inka or alluded to

the royal Aztecs of the past. And on colonial feast

days in the Andes, elites who could trace their descent

from ancient Inka royalty proudly wore elaborately

embroidered tunics along with the maskapaycha,

a scarlet fringe across their foreheads that had once

been the crown of office of the supreme Inka.

By

the end of the 18th century, Creole leaders as well

as indigenous people had grown impatient with the

yoke of colonial rule. Yet the declaration of independence

by the colonies of Spanish America and their transformation

into Latin American nations in the early 19th century

followed no single trajectory, either politically

or visually. In the image of Simón Bolívar,

a leader in the Wars of Independence, it seems that

the tradition of royal portraits was not simply ignored,

but rather transformed into a Republican one. Likewise,

indigenous political accoutrements and symbols familiar

from colonial times were still used in the wake of

independence; few peoples erase the rituals or emblems

of the past completely. Through the 19th century,

well after Independence, the freshly minted nations

of Latin America would come to develop their own visual

expressions for the new contours of their political

power. By

the end of the 18th century, Creole leaders as well

as indigenous people had grown impatient with the

yoke of colonial rule. Yet the declaration of independence

by the colonies of Spanish America and their transformation

into Latin American nations in the early 19th century

followed no single trajectory, either politically

or visually. In the image of Simón Bolívar,

a leader in the Wars of Independence, it seems that

the tradition of royal portraits was not simply ignored,

but rather transformed into a Republican one. Likewise,

indigenous political accoutrements and symbols familiar

from colonial times were still used in the wake of

independence; few peoples erase the rituals or emblems

of the past completely. Through the 19th century,

well after Independence, the freshly minted nations

of Latin America would come to develop their own visual

expressions for the new contours of their political

power.

|