|

The

city street, the nun’s cell, and the gentleman’s

chamber—these spaces framed daily life in Spanish

America. So too did the local church, the indigenous

house, and the market. Today, these sites and the

things that people created for them suggest the ways

that visual culture in Spanish America was patterned

by the mundane and regular as well as spontaneous

rhythms of everyday life.

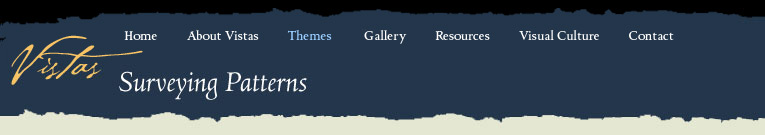

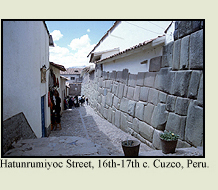

People

in Spanish America, like people in Spain, held cities

to be the source of civilized life, and it was in

cities that a distinct visual culture was first shaped.

The Spanish American city, for instance, was to be

set out on a grid—that is, adhering to an ideal

Renaissance city plan. This physical space was further

modified by social and political ideals. Spaniards

made idealized divisions in their colonies between

separate “republics” of different peoples,

each with different roles and responsibilities. In

the ideal of the city, they were to be carefully segregated

(although, in practice, strict segregation rarely

occurred). The elite home, the convent, the monastery

likewise, were to be worlds whose architecture would

set them apart from the bustle of the marketplace

and the rowdiness of city streets. These interior

spaces, in turn, were intended to mold inhabitants

and shape the practice of everyday life. People

in Spanish America, like people in Spain, held cities

to be the source of civilized life, and it was in

cities that a distinct visual culture was first shaped.

The Spanish American city, for instance, was to be

set out on a grid—that is, adhering to an ideal

Renaissance city plan. This physical space was further

modified by social and political ideals. Spaniards

made idealized divisions in their colonies between

separate “republics” of different peoples,

each with different roles and responsibilities. In

the ideal of the city, they were to be carefully segregated

(although, in practice, strict segregation rarely

occurred). The elite home, the convent, the monastery

likewise, were to be worlds whose architecture would

set them apart from the bustle of the marketplace

and the rowdiness of city streets. These interior

spaces, in turn, were intended to mold inhabitants

and shape the practice of everyday life.

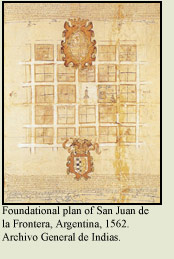

Often,

separate spaces were set up for or by women, a byproduct

of a culture that valued female chastity, domesticity,

and spirituality and held them apart from the values

and practices of more traditionally public and masculine

spheres. For instance, a convent of cloistered nuns

was seen as largely a female world, protected by thick

fortress-like walls from mundane intrusions. And the

elite house also created careful distinctions between

home and the world. In Count Xala’s 18th-century

mansion in Mexico City, for instance, the street level

resounded with the tramp of horses and rattle of carriages

as business was carried out, but the upper floor was

reserved for family and friends. It may be hard to

imagine today, but the women of the Xala family would

spend most of their time, even their lives, on this

floor. Often,

separate spaces were set up for or by women, a byproduct

of a culture that valued female chastity, domesticity,

and spirituality and held them apart from the values

and practices of more traditionally public and masculine

spheres. For instance, a convent of cloistered nuns

was seen as largely a female world, protected by thick

fortress-like walls from mundane intrusions. And the

elite house also created careful distinctions between

home and the world. In Count Xala’s 18th-century

mansion in Mexico City, for instance, the street level

resounded with the tramp of horses and rattle of carriages

as business was carried out, but the upper floor was

reserved for family and friends. It may be hard to

imagine today, but the women of the Xala family would

spend most of their time, even their lives, on this

floor.

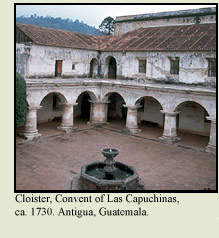

Models

of female roles were conveyed and reflected in visual

images. Portraits of elite women showed them as wives

of powerful men, daughters of wealthy families, usually

ripe for marriage, or brides of Christ. While this

depiction of a sixteen-year-old indigenous woman shows

her holding a flower and a fan, other portraits emphasized

and promoted female religiosity; even in secular portraits,

women grasp rosaries, as if the artist had interrupted

them at prayer. Models

of female roles were conveyed and reflected in visual

images. Portraits of elite women showed them as wives

of powerful men, daughters of wealthy families, usually

ripe for marriage, or brides of Christ. While this

depiction of a sixteen-year-old indigenous woman shows

her holding a flower and a fan, other portraits emphasized

and promoted female religiosity; even in secular portraits,

women grasp rosaries, as if the artist had interrupted

them at prayer.

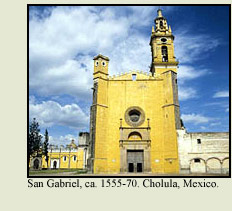

But

religiosity was not only the province of women, and

almost everyone participated in some degree in religious

life. Men, as bishops, monks, or cofradía members,

were typically the leaders of organized religion.

And the tempo of the days—in metropolitan centers

and native communities alike—was set by the

Catholic Church, where the vivid eruption of feasts

and saints’ days overlaid the regular pattern

of the seven-day week, with Sunday at its lead. But

religiosity was not only the province of women, and

almost everyone participated in some degree in religious

life. Men, as bishops, monks, or cofradía members,

were typically the leaders of organized religion.

And the tempo of the days—in metropolitan centers

and native communities alike—was set by the

Catholic Church, where the vivid eruption of feasts

and saints’ days overlaid the regular pattern

of the seven-day week, with Sunday at its lead.

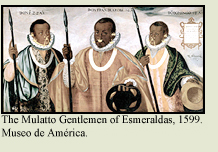

While

buildings and objects show us the contours of powerful

ideologies, the messy practice of living has also

left its residue in the objects and places of everyday

life. While some maps of the cities of Spanish America

display grid plans and segregated neighborhoods, in

actual neighborhoods, Spaniards, Indians, mulattos

and mestizos lived cheek by jowl. Convent, monastery

and elite households offered spacious quarters for

their wealthy residents, and then tiny cells or rooftop

shacks for the servants who came and went to markets

and public spaces. Despite imposing façades,

these buildings were places open to the world. While

buildings and objects show us the contours of powerful

ideologies, the messy practice of living has also

left its residue in the objects and places of everyday

life. While some maps of the cities of Spanish America

display grid plans and segregated neighborhoods, in

actual neighborhoods, Spaniards, Indians, mulattos

and mestizos lived cheek by jowl. Convent, monastery

and elite households offered spacious quarters for

their wealthy residents, and then tiny cells or rooftop

shacks for the servants who came and went to markets

and public spaces. Despite imposing façades,

these buildings were places open to the world.

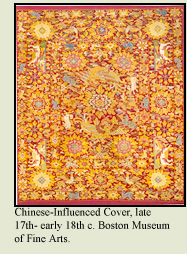

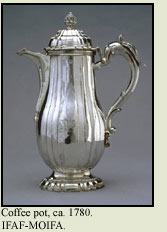

Ideals

about social roles conjoined with everyday practices

to shape the visual environment, as did available

materials. This section of Vistas includes

objects that are distinct to Spanish America, often

because of available products and materials. The glorious

tapestries made in Peru, like this cover for a table

or bed, were woven of local cotton and the wool gathered

from llamas and vicuñas. This cover’s

color comes from cherry-red cochineal, a dye made

from the bodies of crushed insects that had been in

use since pre-Columbian times. A silver teapot called

a pava was designed to brew tea made out of maté

leaves, a popular drink then and now. The heavy and

nearly pure silver used in this and other objects,

like the coffeepot shown below, came from rich mines

in northern Mexico and Bolivia. Ideals

about social roles conjoined with everyday practices

to shape the visual environment, as did available

materials. This section of Vistas includes

objects that are distinct to Spanish America, often

because of available products and materials. The glorious

tapestries made in Peru, like this cover for a table

or bed, were woven of local cotton and the wool gathered

from llamas and vicuñas. This cover’s

color comes from cherry-red cochineal, a dye made

from the bodies of crushed insects that had been in

use since pre-Columbian times. A silver teapot called

a pava was designed to brew tea made out of maté

leaves, a popular drink then and now. The heavy and

nearly pure silver used in this and other objects,

like the coffeepot shown below, came from rich mines

in northern Mexico and Bolivia.

Class

also played a definitive role in the creation of visual

culture and in subsequent understandings of it. Elites

were not the only ones to document their lives and

possessions through legal contracts and wills, but

more of their papers survive, as do their diaries,

travel accounts and spiritual biographies. The objects

the wealthy owned and commissioned, because of their

durable and often precious materials, are also the

ones most likely to have been passed down and preserved

through generations. Reflecting the higher survival

rate of elite documents, objects and architecture,

Vistas by default offers a clearer picture

of high-status lives and spaces. Surviving elite objects

from Spanish America register the powerful influence

of both Spanish and broader European traditions. Style

and function, in particular, suggest how much the

upper classes in Spanish America admired and emulated

the visual culture of Spain. Their campaign to import

European things and ideas into the New World was helped

by presence of large cities. For new ideas spread

quickly within these concentrated milieus, and then

made their way outward to more provincial towns and

communities. Class

also played a definitive role in the creation of visual

culture and in subsequent understandings of it. Elites

were not the only ones to document their lives and

possessions through legal contracts and wills, but

more of their papers survive, as do their diaries,

travel accounts and spiritual biographies. The objects

the wealthy owned and commissioned, because of their

durable and often precious materials, are also the

ones most likely to have been passed down and preserved

through generations. Reflecting the higher survival

rate of elite documents, objects and architecture,

Vistas by default offers a clearer picture

of high-status lives and spaces. Surviving elite objects

from Spanish America register the powerful influence

of both Spanish and broader European traditions. Style

and function, in particular, suggest how much the

upper classes in Spanish America admired and emulated

the visual culture of Spain. Their campaign to import

European things and ideas into the New World was helped

by presence of large cities. For new ideas spread

quickly within these concentrated milieus, and then

made their way outward to more provincial towns and

communities.

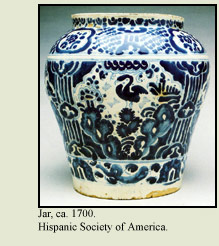

Through

time, the visual culture of Spanish America, first

colored by transatlantic trade, picked up a distinct

tincture from transpacific commerce. The galleons

that were loaded down with New World silver returned

from Asia carrying Chinese silks and blue-and-white

porcelain. By the 18th century, elite homes were likely

to have Spanish-inspired chests inlaid with bone alongside

Asian-inspired lacquered furniture and ceramics, all

made by local artists and craftsmen. So attractive

was this urban elite visual culture that even places

on the far frontiers picked up its pulses like signals

on a radio, as urban products and ideas were transmitted

along internal trade routes. Along the dusty Chihuahua

trail in New Mexico, wealthy residents of Santa Fe

wore imported European brocade and ate off painted

pottery from Puebla, just as did their counterparts

in Mexico City, thousands of miles away. Through

time, the visual culture of Spanish America, first

colored by transatlantic trade, picked up a distinct

tincture from transpacific commerce. The galleons

that were loaded down with New World silver returned

from Asia carrying Chinese silks and blue-and-white

porcelain. By the 18th century, elite homes were likely

to have Spanish-inspired chests inlaid with bone alongside

Asian-inspired lacquered furniture and ceramics, all

made by local artists and craftsmen. So attractive

was this urban elite visual culture that even places

on the far frontiers picked up its pulses like signals

on a radio, as urban products and ideas were transmitted

along internal trade routes. Along the dusty Chihuahua

trail in New Mexico, wealthy residents of Santa Fe

wore imported European brocade and ate off painted

pottery from Puebla, just as did their counterparts

in Mexico City, thousands of miles away.

Because

of the predominance of elite objects among survivals,

it is possible to mistake elite culture and urban

culture for all of visual culture, but this is far

from the case. Rural areas and small towns lay at

a distance from the network of cities and the pulses

of international trade. Here, the particulars of geography,

available materials, and the inheritance of distinct

native traditions were more strongly felt. While it

might be easy at first to mistake a coffee pot from

Lima for one from Mexico City, it would be impossible

to confuse a set of woman’s clothes from Cuzco,

Peru with one from Antigua, Guatemala. Because

of the predominance of elite objects among survivals,

it is possible to mistake elite culture and urban

culture for all of visual culture, but this is far

from the case. Rural areas and small towns lay at

a distance from the network of cities and the pulses

of international trade. Here, the particulars of geography,

available materials, and the inheritance of distinct

native traditions were more strongly felt. While it

might be easy at first to mistake a coffee pot from

Lima for one from Mexico City, it would be impossible

to confuse a set of woman’s clothes from Cuzco,

Peru with one from Antigua, Guatemala.

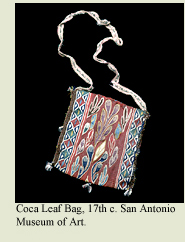

In

rural areas and small towns, it was regional markets,

offering local products, both natural and man-made,

that allowed for the development and expression of

local taste. This woven bag, created in an Andean

town, suggests that aesthetic choices were never limited

to urban centers. Whether this bag was made for sale

in a market or as a personal gift for an indigenous

man or woman is no longer known. Yet regional markets—in

the Andes and elsewhere—had a long history,

dating to well before the arrival of Europeans. Indeed

many survive today. While the physical appearance

of colonial markets rarely exists, the occasional

surviving document offers a glimmer of the market

spectacle and hints at the visual culture of ordinary

lives. As to the range of local styles that once came

out of these markets, perhaps the best visual clues

emerge in the spectrum of contemporary folk arts from

Latin America, and in its craft traditions that are

some of the richest in the world. In

rural areas and small towns, it was regional markets,

offering local products, both natural and man-made,

that allowed for the development and expression of

local taste. This woven bag, created in an Andean

town, suggests that aesthetic choices were never limited

to urban centers. Whether this bag was made for sale

in a market or as a personal gift for an indigenous

man or woman is no longer known. Yet regional markets—in

the Andes and elsewhere—had a long history,

dating to well before the arrival of Europeans. Indeed

many survive today. While the physical appearance

of colonial markets rarely exists, the occasional

surviving document offers a glimmer of the market

spectacle and hints at the visual culture of ordinary

lives. As to the range of local styles that once came

out of these markets, perhaps the best visual clues

emerge in the spectrum of contemporary folk arts from

Latin America, and in its craft traditions that are

some of the richest in the world.

|