|

The

people of Spanish America lived in a world infused

with the sacred. Most believed the perceptible world

to be animated by omniscient forces or beings more

powerful than the living—be they God, Jesus

and the saints, ancestors, or the indigenous deities

that Catholics dismissively called "idols." In this section, Vistas explores the manifold ways individuals in New Spain and Perú developed

visual cultures to mark the sites where interaction

with the otherworld took place. It also looks at the

ways people gave expression, through objects, images

and rituals, to their powerful and life-defining interactions

with the divine.

Without

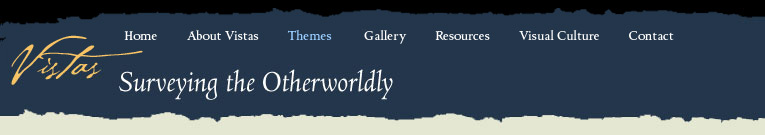

a doubt, from the 16th century onward, Catholicism

dominated the visual culture of Spanish America devoted

to the otherworldly. Saints and angels, the Virgin

Mary, and Jesus were made visible again and again,

in thousands of manifestations. Image-makers might

be artists of the highest acclaim fulfilling a grand

public commission, or individuals seeking a material

focus for personal devotion. They worked in a myriad

of materials—with paint applied to canvas and

walls, inks on paper, or gesso and wood, tagua nut,

maguey fiber. The most precious materials adorned

figures destined for august patrons and settings:

elite homes, convents or cathedrals. Yet neither the

cost of the materials nor the degree of craftsmanship

determined the spiritual effectiveness of an image.

A humbly sculpted image of wood of the Virgin Mary

could be just as revered as one bedecked in azure

robes and pearls. Without

a doubt, from the 16th century onward, Catholicism

dominated the visual culture of Spanish America devoted

to the otherworldly. Saints and angels, the Virgin

Mary, and Jesus were made visible again and again,

in thousands of manifestations. Image-makers might

be artists of the highest acclaim fulfilling a grand

public commission, or individuals seeking a material

focus for personal devotion. They worked in a myriad

of materials—with paint applied to canvas and

walls, inks on paper, or gesso and wood, tagua nut,

maguey fiber. The most precious materials adorned

figures destined for august patrons and settings:

elite homes, convents or cathedrals. Yet neither the

cost of the materials nor the degree of craftsmanship

determined the spiritual effectiveness of an image.

A humbly sculpted image of wood of the Virgin Mary

could be just as revered as one bedecked in azure

robes and pearls.

Looking

at visual expressions of the otherworld gives one

view, albeit a carefully focused one, on the larger

landscape of religious belief. For every painting

of the Virgin or statue of a saint, there were thousands

upon thousands of rituals through which people made

connections to the otherworld; these have left little

trace in the visual or historical record. Nuns prayed

silently behind convent walls, people recited their

rosaries before sleep; barefoot farmers lit candles

before prints of saints affixed to the wall. The otherworld

was also evoked in poems read from a book, sermons

heard in church, or songs sung in a plaza. This written

and oral world was the accompaniment to the visual

one glimpsed here. Looking

at visual expressions of the otherworld gives one

view, albeit a carefully focused one, on the larger

landscape of religious belief. For every painting

of the Virgin or statue of a saint, there were thousands

upon thousands of rituals through which people made

connections to the otherworld; these have left little

trace in the visual or historical record. Nuns prayed

silently behind convent walls, people recited their

rosaries before sleep; barefoot farmers lit candles

before prints of saints affixed to the wall. The otherworld

was also evoked in poems read from a book, sermons

heard in church, or songs sung in a plaza. This written

and oral world was the accompaniment to the visual

one glimpsed here.

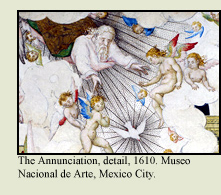

Catholicism

was a religion imposed—often violently—on

America. Long before the conquest, pre-Hispanic societies

had their own highly developed religions and ritual

lives. In the 16th century, early evangelizers, men

of the cloth, arrived with men of the sword and destroyed

thousands, if not tens of thousands, of indigenous

temples and shrines, sacred books and sculptures.

European conquerors degraded native deities, labeling

them “idols” and suppressing their visual

expression. The mendicant friars who were charged

with evangelizing native peoples quickly realized

that one belief system could not be substituted for

another merely by force, and poured their energies

into educating and indoctrinating the young. They

commissioned churches and reset public celebrations

to the Church calendar. Catholicism

was a religion imposed—often violently—on

America. Long before the conquest, pre-Hispanic societies

had their own highly developed religions and ritual

lives. In the 16th century, early evangelizers, men

of the cloth, arrived with men of the sword and destroyed

thousands, if not tens of thousands, of indigenous

temples and shrines, sacred books and sculptures.

European conquerors degraded native deities, labeling

them “idols” and suppressing their visual

expression. The mendicant friars who were charged

with evangelizing native peoples quickly realized

that one belief system could not be substituted for

another merely by force, and poured their energies

into educating and indoctrinating the young. They

commissioned churches and reset public celebrations

to the Church calendar.

By

the 17th century, Catholicism had taken hold in indigenous

communities. But not surprisingly, Church orthodoxy

was, and still is, perennially modified by local practice

in the Americas (as it was in Europe as well) and

shaped by enduring native beliefs. In fact, one scholar

of Andean religion, Kenneth Mills, speaks of the “many

faces of Christianity,” to emphasize the range

and varied complexion of Christian practices that

developed in Spanish America. By

the 17th century, Catholicism had taken hold in indigenous

communities. But not surprisingly, Church orthodoxy

was, and still is, perennially modified by local practice

in the Americas (as it was in Europe as well) and

shaped by enduring native beliefs. In fact, one scholar

of Andean religion, Kenneth Mills, speaks of the “many

faces of Christianity,” to emphasize the range

and varied complexion of Christian practices that

developed in Spanish America.

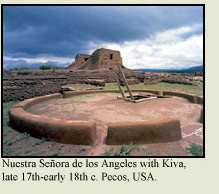

As

Catholics, native peoples As

Catholics, native peoples

did much to define the nature of

otherworldly beings and sites of interaction with

them. In New Spain, the Virgin of Guadalupe left her

image upon a poor Nahua man’s cloak. Slaves

from Africa also had a role in shaping Catholicism:

in the Caribbean and in Brazil, African orishas mingled

with saints. In a number of instances, European-born

or Creole clergy encouraged theater, dance and processions,

allowing local practice to overlap with Catholic performance,

as a way of strengthening the Catholic faith. In other

cases, they accepted indigenous practices with guarded

tolerance. In the Andes, the Jesuits sometimes allowed

khipus—mnemonic devices made of knotted cords—to

be used like rosaries. And in New Mexico, kivas were

built within the walls of a few monasteries. At Pecos,

for instance, the ruined walls of the convento stand

near a subterranean, circular kiva. Modern photographs

like this one, which shows the kiva’s reconstructed

roofing and ladder entryway, reveal the intimate link

between Christian and Puebloan architectural forms

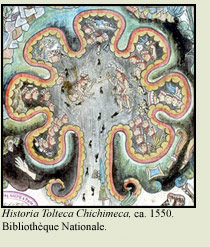

Despite

its power, however, the Church was unable to erase

native

Despite

its power, however, the Church was unable to erase

native

histories, which often recorded moments of contact

with non-Christian or pre-Christian otherworlds—particularly

via ancestors and past heroes, whom many people believed

were active forces in their contemporary worlds. This

Nahua manuscript, called the Historia Tolteca

Chichimeca, painted in the town of Cuauhtinchan

in the mid-16th century offers one example. The scene

describes and depicts the cave of Colhuacatepec, a

primordial point of origin whence founders of the

town of Cuauhtinchan emerged: a Nahua Genesis, not

a Christian one.

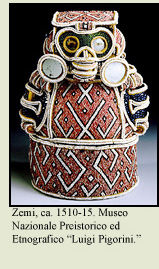

History

was entwined with lives of the dead, and these selfsame

dead were often conduits to otherworldly places and

knowledge. Thus, many indigenous peoples revered the

funerary remains of ancestors, particularly patriarchs

of communities or founders of lineages. In the Caribbean,

zemis were associated with deceased leaders—some,

such as the one here, could hold the ashes of cremated

bodies. And in Andes, the mummies of Inka kings and

queens, as well as local leaders were considered one

type of w’aka, or sacred entity. These mummy

bundles, elaborately dressed, played a large role

in the visual culture of pre-Hispanic times, when

they were taken out in public, fed and honored as

mediators between this world and the next. Yet conquerors

and priests banned many visual expressions of the

ancestors, including zemis and mummy bundles. History

was entwined with lives of the dead, and these selfsame

dead were often conduits to otherworldly places and

knowledge. Thus, many indigenous peoples revered the

funerary remains of ancestors, particularly patriarchs

of communities or founders of lineages. In the Caribbean,

zemis were associated with deceased leaders—some,

such as the one here, could hold the ashes of cremated

bodies. And in Andes, the mummies of Inka kings and

queens, as well as local leaders were considered one

type of w’aka, or sacred entity. These mummy

bundles, elaborately dressed, played a large role

in the visual culture of pre-Hispanic times, when

they were taken out in public, fed and honored as

mediators between this world and the next. Yet conquerors

and priests banned many visual expressions of the

ancestors, including zemis and mummy bundles.

This

indigenous vision of the dead and their connection

to the otherworld contrasted to that of more orthodox

Catholicism in the colonies. This difference is visible

in the deathbed portraits commissioned in Spanish

America. The purposes of these pictures seems to have

been to commemorate lives well lived and to inspire

members of the community of the living. Neither the

portraits, nor the souls of the people they represented

were objects of devotion, or active forces in the

otherworld. But such portraits, like this one of a

nun bedecked in her habit and crown of flowers, remind

contemporary viewers how much death surrounded the

living—and how many cultural products, both

visual and rhetorical, went into maintaining connections

to the dead and attempting to understand the worlds

where they dwelt. This

indigenous vision of the dead and their connection

to the otherworld contrasted to that of more orthodox

Catholicism in the colonies. This difference is visible

in the deathbed portraits commissioned in Spanish

America. The purposes of these pictures seems to have

been to commemorate lives well lived and to inspire

members of the community of the living. Neither the

portraits, nor the souls of the people they represented

were objects of devotion, or active forces in the

otherworld. But such portraits, like this one of a

nun bedecked in her habit and crown of flowers, remind

contemporary viewers how much death surrounded the

living—and how many cultural products, both

visual and rhetorical, went into maintaining connections

to the dead and attempting to understand the worlds

where they dwelt.

But

for all the ways Catholic practice was transformed

by folk practices and local beliefs, the Church itself

was not always tolerant. The Inquisition punished

people for practices it deemed idolatrous and worked

to pull belief towards its orthodox teachings. While

its main targets were rarely indigenous people, its

presence was well known. In Lima, the Jesuit-run Casa

de Santa Cruz was both a prison for those accused

by the Inquisition and also a school for native leaders.

Native communities in the countryside from Mexico

through Peru were more often targeted by local bishops,

who sent investigators of “idolatry” to

rout out unorthodox practices. The continued existence,

in places like Huarochiri, Peru, of native healers

and diviners, their use of keros, drums, medicine

bundles, and ceremonial garments (found by Church

investigators) signals that the Church never fully

sanctioned or monopolized all means of access to the

otherworld. But

for all the ways Catholic practice was transformed

by folk practices and local beliefs, the Church itself

was not always tolerant. The Inquisition punished

people for practices it deemed idolatrous and worked

to pull belief towards its orthodox teachings. While

its main targets were rarely indigenous people, its

presence was well known. In Lima, the Jesuit-run Casa

de Santa Cruz was both a prison for those accused

by the Inquisition and also a school for native leaders.

Native communities in the countryside from Mexico

through Peru were more often targeted by local bishops,

who sent investigators of “idolatry” to

rout out unorthodox practices. The continued existence,

in places like Huarochiri, Peru, of native healers

and diviners, their use of keros, drums, medicine

bundles, and ceremonial garments (found by Church

investigators) signals that the Church never fully

sanctioned or monopolized all means of access to the

otherworld.

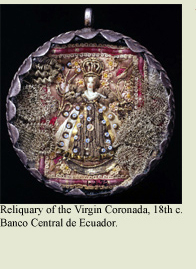

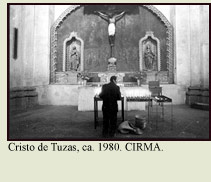

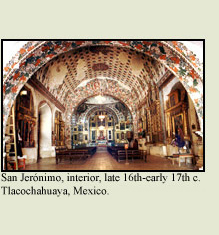

The

powerful need of Spanish Americans to access otherworlds

is no way better attested to than through its landscape—to

this day blanketed with colonial churches and cathedrals.

Through performance of the mass in these churches,

priests conducted rites that turned wine and bread

into the blood and body of Jesus. The accoutrements

for such services—from priestly robes to candlesticks,

altar cloths, and monstrances—set the stage

for invoking the divine. In addition, when mass was

offered, whether in a cloistered convent, a Maya town,

or a magnificent cathedral, images of saints and angels,

Church fathers and royal patrons, Jesus and Mary often

adorned the space. On retablos and ceilings, in side

chapels and choirs, images filled the churches of

Spanish America. With scenes from the Bible, heaven

and hell, churches offered visual, as well as ritual,

access to the Christian otherworld. The

powerful need of Spanish Americans to access otherworlds

is no way better attested to than through its landscape—to

this day blanketed with colonial churches and cathedrals.

Through performance of the mass in these churches,

priests conducted rites that turned wine and bread

into the blood and body of Jesus. The accoutrements

for such services—from priestly robes to candlesticks,

altar cloths, and monstrances—set the stage

for invoking the divine. In addition, when mass was

offered, whether in a cloistered convent, a Maya town,

or a magnificent cathedral, images of saints and angels,

Church fathers and royal patrons, Jesus and Mary often

adorned the space. On retablos and ceilings, in side

chapels and choirs, images filled the churches of

Spanish America. With scenes from the Bible, heaven

and hell, churches offered visual, as well as ritual,

access to the Christian otherworld.

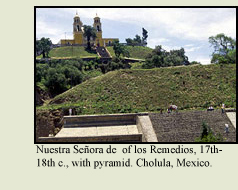

It

was not only buildings that marked the sites of otherworldly

access. In pre-Hispanic Mexico, shrines and temples

were built above caves or to align with the planet

Venus as it swept across the sky. In the Andes, w’akas

could take the form of mountain peaks, streams, and

prominent rock outcroppings. After the Spanish conquest,

colonial churches were often built near, if not upon,

these sacred sites. While these churches undoubtedly

drew on pre-existing understandings of the sacred

landscape, they also tended to displace indigenous

understandings of the otherworld, or subsume those

ideas within Catholic ones. It

was not only buildings that marked the sites of otherworldly

access. In pre-Hispanic Mexico, shrines and temples

were built above caves or to align with the planet

Venus as it swept across the sky. In the Andes, w’akas

could take the form of mountain peaks, streams, and

prominent rock outcroppings. After the Spanish conquest,

colonial churches were often built near, if not upon,

these sacred sites. While these churches undoubtedly

drew on pre-existing understandings of the sacred

landscape, they also tended to displace indigenous

understandings of the otherworld, or subsume those

ideas within Catholic ones.

Certain

peoples—beyond the priests ordained by the Church—had

privileged access to otherworlds. Just as Europe produced

visionaries, like Saint Catherine, who dreamed of

a mystic marriage to Christ, or Saint Francis, who

bore the wounds of Jesus on his hands and feet, so

too did Spanish America. Certain local visionaries

captured huge followings and many were promoted by

the Church. Spanish-American born visionaries and

saints, like Saint Rose of Lima, Madre María

de Jesus of Tunja, or Saint Martín de Porras,

reinforced the idea that the portals to the otherworld

could be opened to the living. But, like the visions

themselves, access points to the sacred were also

difficult for Church leaders to fully anticipate.

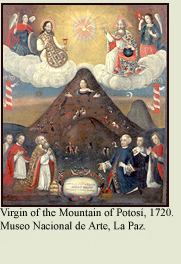

Miracle working saints, like the Virgin of Ocotlán,

the Virgin of Potosí and the Virgin of Cocharcas,

appeared in surprising places to unlikely visionaries.

And pilgrimages to the shrines of such Virgins became

integral to the landscape and ritual practices of

the sacred in Spanish America. Certain

peoples—beyond the priests ordained by the Church—had

privileged access to otherworlds. Just as Europe produced

visionaries, like Saint Catherine, who dreamed of

a mystic marriage to Christ, or Saint Francis, who

bore the wounds of Jesus on his hands and feet, so

too did Spanish America. Certain local visionaries

captured huge followings and many were promoted by

the Church. Spanish-American born visionaries and

saints, like Saint Rose of Lima, Madre María

de Jesus of Tunja, or Saint Martín de Porras,

reinforced the idea that the portals to the otherworld

could be opened to the living. But, like the visions

themselves, access points to the sacred were also

difficult for Church leaders to fully anticipate.

Miracle working saints, like the Virgin of Ocotlán,

the Virgin of Potosí and the Virgin of Cocharcas,

appeared in surprising places to unlikely visionaries.

And pilgrimages to the shrines of such Virgins became

integral to the landscape and ritual practices of

the sacred in Spanish America.

Today,

parades and processions are most often held to celebrate

historical events, secular holidays like Independence

Day, and sports victories. In Spanish America, they

were often a way of visually reenacting the porousness

between the otherworld of God and the saints and the

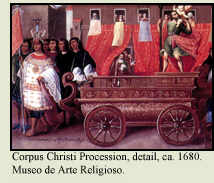

human community. This extraordinary 17th-century painting

shows such a parade during the important feast of

Corpus Christi in Cuzco. In it, Andean leaders lead

an elaborate cart, bearing a statue of Saint Christopher

through the streets of the city. As depicted by the

painter, both the wooden saint and human participants

seem equally alive, equally part of this community. Today,

parades and processions are most often held to celebrate

historical events, secular holidays like Independence

Day, and sports victories. In Spanish America, they

were often a way of visually reenacting the porousness

between the otherworld of God and the saints and the

human community. This extraordinary 17th-century painting

shows such a parade during the important feast of

Corpus Christi in Cuzco. In it, Andean leaders lead

an elaborate cart, bearing a statue of Saint Christopher

through the streets of the city. As depicted by the

painter, both the wooden saint and human participants

seem equally alive, equally part of this community.

|