|

When

Christopher Columbus guided his ships west out of

the Spanish port of Palos, near Cadiz,

perhaps twenty-five million people made their home

in the Americas. Two empires were at their apogee,

controlling enormous swaths of territory. In the north

was the Aztec and the south, the Inka. Their peoples

carried on sophisticated lives in cities and towns,

producing elaborate objects and monuments. Within

each

empire, peoples of distinct languages and customs—Mixtecs,

Zapotecs, Guaraní, Chocho, and Cañari,

to

name just a few—made their lives in spaces defined

by the capital cities of Tenochtitlan and Cuzco, their

existences shaped by complex trade networks and local

politics.

In

Vistas, the colonial period is understood

as the staging ground for constructing and re-constructing

pre-Columbian history, from 16th-century initial memories

to 19th-century proto-national concepts. In considering

the many ways in which colonial peoples made sense

of the pre-Columbian, the interpretations presented

here rest on the premise that there was no single,

stable pre-Columbian past in colonial Spanish America

(just as there is no single, stable pre-Columbian

or colonial past today). And it is precisely this

diversity and fluidity that Vistas seeks

to highlight, for it was precisely this diversity

and fluidity that characterized the pre-Columbian

in colonial times. In

Vistas, the colonial period is understood

as the staging ground for constructing and re-constructing

pre-Columbian history, from 16th-century initial memories

to 19th-century proto-national concepts. In considering

the many ways in which colonial peoples made sense

of the pre-Columbian, the interpretations presented

here rest on the premise that there was no single,

stable pre-Columbian past in colonial Spanish America

(just as there is no single, stable pre-Columbian

or colonial past today). And it is precisely this

diversity and fluidity that Vistas seeks

to highlight, for it was precisely this diversity

and fluidity that characterized the pre-Columbian

in colonial times.

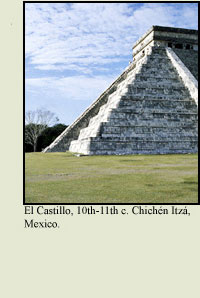

Across

the Americas, the history of indigenous cultures is

so long and so vibrant that by 1500, hundreds of histories

could be found inscribed in abandoned cities and half-buried

settlements. In the Yucatán, the landscape

was punctuated by crumbling ruins that had once been

the center of dazzling whitewashed cities. Built by

the ancestors of the Maya, many sites still held hieroglyphic

texts carved in stone or painted inside building walls.

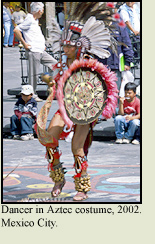

In the highlands of Peru, Machu Picchu, seen in the

photograph, had been an Inka royal retreat. The city

was abandoned probably in the early 16th century;

its walls overgrown with orchid and bromeliad, even

as vibrant Andean communities made their living nearby. Across

the Americas, the history of indigenous cultures is

so long and so vibrant that by 1500, hundreds of histories

could be found inscribed in abandoned cities and half-buried

settlements. In the Yucatán, the landscape

was punctuated by crumbling ruins that had once been

the center of dazzling whitewashed cities. Built by

the ancestors of the Maya, many sites still held hieroglyphic

texts carved in stone or painted inside building walls.

In the highlands of Peru, Machu Picchu, seen in the

photograph, had been an Inka royal retreat. The city

was abandoned probably in the early 16th century;

its walls overgrown with orchid and bromeliad, even

as vibrant Andean communities made their living nearby.

Living

peoples anchored their own pasts to these ancient

places, sustained and reshaped histories through their

own oral narratives, animated them through ritual

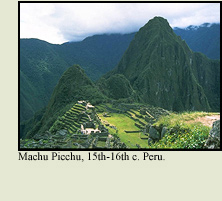

practice. For instance, the city of Teotíhuacan

was abandoned seven centuries before European conquest

and colonization. Once the most populous city with

the largest structures in North America, Teotíhuacan

was a ghost town in 1521 when Hernán Cortés

and his allies marched on the Aztecs. Yet the ruined

pyramids had not been forgotten. The Aztecs called

Teotíhuacan "The City of the Gods,"

after those they thought responsible for the monumental

architecture, and every twenty days the Aztec king

and his high priests made a ritual pilgrimage there.

Living

peoples anchored their own pasts to these ancient

places, sustained and reshaped histories through their

own oral narratives, animated them through ritual

practice. For instance, the city of Teotíhuacan

was abandoned seven centuries before European conquest

and colonization. Once the most populous city with

the largest structures in North America, Teotíhuacan

was a ghost town in 1521 when Hernán Cortés

and his allies marched on the Aztecs. Yet the ruined

pyramids had not been forgotten. The Aztecs called

Teotíhuacan "The City of the Gods,"

after those they thought responsible for the monumental

architecture, and every twenty days the Aztec king

and his high priests made a ritual pilgrimage there.

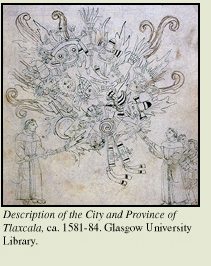

Before

the arrival of Europeans, then, the indigenous past

was both well honored and open to reinterpretation

by the descendants of those who came before. This

was a process that depended upon and lent new meanings

to visual culture, as peoples actively recast old

forms and places, reworking and reinterpreting them.

It was also a process that continued after the arrival

of Europeans, but was made more difficult by the profound

and devastating changes that were unleashed soon after

1492. The conquistadors had little interest in indigenous

histories: many an Inka witnessed the Spanish conquistadors

destroying ancient shrines—places where the

dead could speak to the living—in their zealous

search for silver and gold. Often Spaniards viewed

local history—embedded in objects and architectural

spaces—as an impediment to conquest. Thus, Aztecs

saw their glorious capital city reduced to rubble,

the life-size portraits of the Aztec kings gouged

off the living rock, and, as seen below, sacred objects

and manuscripts put to the torch. The transmission

of oral histories and living memories was severely

reduced by the countless deaths brought by new diseases.

While about twenty-five million Americans witnessed

the dawn of the 16th century, fewer than one million

would see the 17th. Before

the arrival of Europeans, then, the indigenous past

was both well honored and open to reinterpretation

by the descendants of those who came before. This

was a process that depended upon and lent new meanings

to visual culture, as peoples actively recast old

forms and places, reworking and reinterpreting them.

It was also a process that continued after the arrival

of Europeans, but was made more difficult by the profound

and devastating changes that were unleashed soon after

1492. The conquistadors had little interest in indigenous

histories: many an Inka witnessed the Spanish conquistadors

destroying ancient shrines—places where the

dead could speak to the living—in their zealous

search for silver and gold. Often Spaniards viewed

local history—embedded in objects and architectural

spaces—as an impediment to conquest. Thus, Aztecs

saw their glorious capital city reduced to rubble,

the life-size portraits of the Aztec kings gouged

off the living rock, and, as seen below, sacred objects

and manuscripts put to the torch. The transmission

of oral histories and living memories was severely

reduced by the countless deaths brought by new diseases.

While about twenty-five million Americans witnessed

the dawn of the 16th century, fewer than one million

would see the 17th.

Spanish

conquerors and colonial officials tried to overwrite

these multiple histories with one of their own making.

To begin, they invented a new category of indio,

a name they gave to any native person from the Indies,

as Spanish possessions in the New World were called

(“natural” was also used). Spanish

conquerors and colonial officials tried to overwrite

these multiple histories with one of their own making.

To begin, they invented a new category of indio,

a name they gave to any native person from the Indies,

as Spanish possessions in the New World were called

(“natural” was also used). Indio was far more than convenient shorthand;

in Spanish America, the indio was someone

of different rights, a different order of personhood.

Indios were legal minors, cultural children.

And as they forced the status of indio upon

millions of dissimilar and distinct peoples, Spaniards

tried to fashion a common history for the Indies,

and connect it to Christian ideas about the shape

of history. Writers of the time called this history

a narrative “of the Indies.” It often

began with the creation of the earth, proceeded rapidly

to the indigenous empires of the 14th and 15th centuries,

and then climaxed with a successful Spanish conquest

and imposition of a universal Christianity. Today,

a fuller sense of the scope and depth of America’s

past exists, yet the blanket term “pre-Hispanic”

or “pre-Columbian” (that is, before Columbus)

is still used to describe the history of America before

the arrival of Europeans.

Indio was far more than convenient shorthand;

in Spanish America, the indio was someone

of different rights, a different order of personhood.

Indios were legal minors, cultural children.

And as they forced the status of indio upon

millions of dissimilar and distinct peoples, Spaniards

tried to fashion a common history for the Indies,

and connect it to Christian ideas about the shape

of history. Writers of the time called this history

a narrative “of the Indies.” It often

began with the creation of the earth, proceeded rapidly

to the indigenous empires of the 14th and 15th centuries,

and then climaxed with a successful Spanish conquest

and imposition of a universal Christianity. Today,

a fuller sense of the scope and depth of America’s

past exists, yet the blanket term “pre-Hispanic”

or “pre-Columbian” (that is, before Columbus)

is still used to describe the history of America before

the arrival of Europeans.

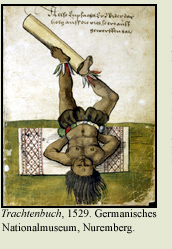

The

interpretations and images presented here explore

how peoples living in Europe and Spanish America made

sense of this pre-Columbian history, especially through

visual culture. Europe had little grasp of the depth

and complexity of indigenous histories, and the Indies

and their indio inhabitants could be a source

of awe and amusement. This was particularly true in

the 16th century, when native peoples were imported

to Europe as wondrous performers. Their crafted works

were taken from America as gifts for kings and cardinals.

Clearly European perspectives on the New World were

complex. Some defended the rights and privileges of

native peoples, yet prejudice and rumors of devil-worship

and cannibalism also became fixed in the European

imagination. And images of such evils circulated widely,

in books, prints, and the salons of the wealthy. The

interpretations and images presented here explore

how peoples living in Europe and Spanish America made

sense of this pre-Columbian history, especially through

visual culture. Europe had little grasp of the depth

and complexity of indigenous histories, and the Indies

and their indio inhabitants could be a source

of awe and amusement. This was particularly true in

the 16th century, when native peoples were imported

to Europe as wondrous performers. Their crafted works

were taken from America as gifts for kings and cardinals.

Clearly European perspectives on the New World were

complex. Some defended the rights and privileges of

native peoples, yet prejudice and rumors of devil-worship

and cannibalism also became fixed in the European

imagination. And images of such evils circulated widely,

in books, prints, and the salons of the wealthy.

As

early as 1550, when Europeans first began to stabilize,

and indeed create a pre-Columbian past that paralleled

their own sense of history, they often collaborated

with native elders. Educated natives and mestizos—some

of whom had moved to Europe, others who remained in

Spanish America—also took up the pen to write

accounts of the past. Yet legions of others, be they

Zapotec, Nahua, Otomí, Chuncho, or Inka, held

on to their specific forms of cultural memory through

the preservation and creation of objects and rituals.

At times, the iconography of images—their depiction

of ancient rites or ancestors—directly referenced

the past. In other instances, it was the craftsmanship

or choice of materials that kept pre-Columbian traditions

and memories alive. In all instances, however, indigenous

contributions to colonial visual culture are a distinguishing

feature of Latin American history and colonization. As

early as 1550, when Europeans first began to stabilize,

and indeed create a pre-Columbian past that paralleled

their own sense of history, they often collaborated

with native elders. Educated natives and mestizos—some

of whom had moved to Europe, others who remained in

Spanish America—also took up the pen to write

accounts of the past. Yet legions of others, be they

Zapotec, Nahua, Otomí, Chuncho, or Inka, held

on to their specific forms of cultural memory through

the preservation and creation of objects and rituals.

At times, the iconography of images—their depiction

of ancient rites or ancestors—directly referenced

the past. In other instances, it was the craftsmanship

or choice of materials that kept pre-Columbian traditions

and memories alive. In all instances, however, indigenous

contributions to colonial visual culture are a distinguishing

feature of Latin American history and colonization.

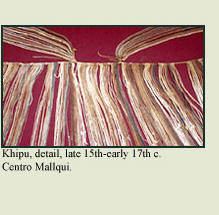

Throughout

the history of Spanish America, indigenous peoples

used visual things to both remember and represent

their past. Through the threads of memory and ancestry—at

times animated by oral recitations and performances

on feast days or other public occasions—a special

connection to the pre-Columbian past was claimed.

This connection could be quite literal, as when native

historians of the 16th and 17th centuries had the

knowledge to interpret khipus and ancient pictorial

manuscripts. Such objects, with their origins in pre-Hispanic

times, were often safeguarded in local towns in the

colonial period or else were ecopied. Through written

words and painted imagery, often in alphabetic script

and in paper and inks introduced by friars, indigenous

people also recalled and remade the past for their

own purposes. Throughout

the history of Spanish America, indigenous peoples

used visual things to both remember and represent

their past. Through the threads of memory and ancestry—at

times animated by oral recitations and performances

on feast days or other public occasions—a special

connection to the pre-Columbian past was claimed.

This connection could be quite literal, as when native

historians of the 16th and 17th centuries had the

knowledge to interpret khipus and ancient pictorial

manuscripts. Such objects, with their origins in pre-Hispanic

times, were often safeguarded in local towns in the

colonial period or else were ecopied. Through written

words and painted imagery, often in alphabetic script

and in paper and inks introduced by friars, indigenous

people also recalled and remade the past for their

own purposes.

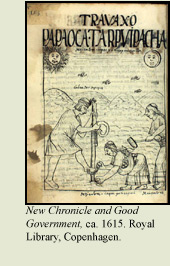

Just

as they had before the arrival of the Spanish, indigenous

histories always took form and meaning in ways useful

for the present. For instance, the Andean writer Felipe

Guaman Poma de Ayala (who wrote and painted in the

17th century) did not merely register the glories

of pre-Columbian times. Rather he shaped his history,

with scenes like this one, as a call to reestablish

native Andean rule. Descendants of the Inka and the

Aztec also invoked imperial histories for the express

purpose of holding onto threatened rights and properties.

Yet others represented their ancestral past as something

distinctly not Spanish and not Aztec (or not Inka)—in

a new, hybrid style that drew from multiple traditions.

And in this way they reaffirmed their separate ethnic

or town identities. Just

as they had before the arrival of the Spanish, indigenous

histories always took form and meaning in ways useful

for the present. For instance, the Andean writer Felipe

Guaman Poma de Ayala (who wrote and painted in the

17th century) did not merely register the glories

of pre-Columbian times. Rather he shaped his history,

with scenes like this one, as a call to reestablish

native Andean rule. Descendants of the Inka and the

Aztec also invoked imperial histories for the express

purpose of holding onto threatened rights and properties.

Yet others represented their ancestral past as something

distinctly not Spanish and not Aztec (or not Inka)—in

a new, hybrid style that drew from multiple traditions.

And in this way they reaffirmed their separate ethnic

or town identities.

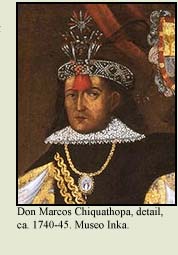

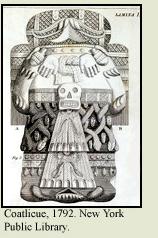

By

the time of independence in the early 19th century,

Creoles—not only native people—considered

pre-Columbian history as their own. Creole nationalists

were drawn to the imperial cultures encountered by

the conquerors, the Inka and Aztec, as illustrious

models and ancestral heroes of their homeland. And

while the images that Creoles generated of ancient

rulers in Cuzco or sculptures of the rulers of Tenochtitlan

were more often fanciful than factual, these representations

must be taken seriously as a set of practices through

which pre-Columbian history and visual culture were

invested with meaning in the late colonial period. By

the time of independence in the early 19th century,

Creoles—not only native people—considered

pre-Columbian history as their own. Creole nationalists

were drawn to the imperial cultures encountered by

the conquerors, the Inka and Aztec, as illustrious

models and ancestral heroes of their homeland. And

while the images that Creoles generated of ancient

rulers in Cuzco or sculptures of the rulers of Tenochtitlan

were more often fanciful than factual, these representations

must be taken seriously as a set of practices through

which pre-Columbian history and visual culture were

invested with meaning in the late colonial period.

|